Top-Level Contents:

- Summary of this Limited Critique

- Brinckmann’s Book “Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings”

- Defining 3 Positions about Mushrooms in Christian Art & Historical Practice

- An Attempted Argument for the Moderate Mushroom Theory of Christianity: The Vial that Looks Like Amanita

- Hatsis Is Worth Limited Critique Regarding Psilocybe in Greek & Christian Art

- Search Hit Counts on Various Plants in the Book

- Free-form Comments About Hatsis’ Book

- Table of Contents for Part II: Psychedelic Mystery Traditions in Ancient Christianity

- Article: The Christian Radish Cult

- Article: The Mushroom in Mommy Fortuna’s Midnight Carnival

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

Detailed Contents:

Summary of this Limited Critique

Michael Hoffman, October 31, 2020

I’m looking for coverage of:

- Psilocybe in Greek & Christian art.

- Psilocybe in mixed-wine banqueting, mystery-religion initiation, and esoteric Christianity.

Page Numbers for Psilocybe in Greek & Christian Art

- Hellenistic: tbd

- Christendom: tbd

Page numbers according to Kindle ebook.

Book Links

Book:

Psychedelic Mystery Traditions: Spirit Plants, Magical Practices, and Ecstatic States – A comprehensive look at the long tradition of psychedelic magic and religion in Western Civilization

Tom Hatsis

PsychedelicWitch, Amazon

September 2018, Park Street Press

I have the Kindle ebook, which is good for Search, but poor for orientation and reading. I need to try harder, eg. use on-screen highlighting.

To conduct this analysis, I need to also get the printed book, for orientation, highlighting, notes, coverage, engagement, and reading.

Quote about “Sound, Tried-and-True Historical Criteria”

“The supposed mushrooms that appear in Christian art are easily explained away through sound, tried-and-true historical criteria, which those who still support the theory (in one variety or another) have simply not considered.” — p. 139

These historical criteria are not identified or summarized in this book, even though the above is an extreme position on a key topic, and even though this book is about psychedelics in Western religious history.

Instead, the reader is directed to the author’s online articles, which specifically aim to debunk the “Secret Christian Amanita Cult” theory of Allegro, Irvin, and Rush.

Articles

Hatsis’ articles mentioned in his book present many good images of mushrooms in Christian art.

The articles argue that:

o The many mushroom-shaped images in Christian art can be interpreted as non-mushroom items, and therefore should be so interpreted, exclusively.

o Even if the mushroom shapes in Christian art are intended as mushrooms, there’s no proof that they represent psychoactive mushrooms.

o These same stylized mushroom trees appear in menageries, which have nothing to do with religious mythology, thereby disproving that these mushroom-trees are meant as psychoactive.

That is the “sound, tried-and-true historical criteria” which the author presents (but not in this book) to support the extreme, Wasson/Panofsky-type position that “The supposed mushrooms that appear in Christian art are easily explained away.”

The Criteria by Which Panofsky Dismisses Mushrooms in Christian Art: One Short Book, by One Author, in 1906, in German, restricted to Mushroom-Trees

The ghost of Panofsky is being channeled through Hatsis the necromancer.

The Wasson/Panofsky position explains-away mushrooms in Christian art by the following claims, arguments, reasoning, and interpretive framework (without presenting or responding to any counter-argument or other candidate interpretive framework): this supposed treatment of the matter by “the art historians” amounts to only a single book by a single author (Brinckmann, 1906), which Wasson doesn’t even let the world see.

I haven’t found a single mention of Brinckmann by Wasson, yet Wasson rests his entire case (against mushrooms in Christian art) on this one book, which he withholds from us.

The Wasson/Panofsky claim and case for dismissing mushrooms in Christian art rests on nothing but a single book (in German). Even if this lone book and author are great on this topic, it’s a long shot to say “This one book exists, therefore, art historians have collectively concluded with finality that there are no psychoactive mushrooms in Christian art”.

Is that all you’ve got, a single book by a single author? That’s supposed to represent the critical verdict of the entire field of art historians, on the subject of psychoactive mushrooms in Christian art?

As good as Clark Heinrich’s 1995 book Strange Fruit is, a single book by a single author is much less adequate than Wasson claims, when he tries to characterize it as if the entire art-history world has already treated the matter with finality.

Wasson Hides the Single Art-History Work on Which He Bases His Claim

Wasson and Allegro on the Tree of Knowledge as Amanita

Michael Hoffman, 2006, Journal of Higher Criticism

Subsection Panofsky, 1952 in my article shows Panofsky’s letter as presented in SOMA by Wasson:

http://www.egodeath.com/WassonEdenTree.htm#_Toc135889188

As I cited in that article: in the book SOMA, R. Gordon Wasson quotes the art historian Erwin Panofsky as follows, providing only ellipses ( … ), where a citation would be needed to substantiate Wasson’s claim that art historians have already discussed, and soundly dismissed, mushroom trees in Christian art:

“The plant in this fresco has nothing whatever to do with mushrooms, and the similarity with Amanita muscaria is purely fortuitous. The Plaincourault fresco is only one example – and, since the style is provincial, a particularly deceptive one – of a conventionalized tree type, prevalent in Romanesque and early Gothic art, which art historians actually refer to as a ‘mushroom tree’ or in German, Pilzbaum. It comes about by the gradual schematization of the impressionistically rendered Italian pine tree in Roman and early Christian painting, and there are hundreds of instances exemplifying this development – unknown of course to mycologists. … What the mycologists have overlooked is that the medieval artists hardly ever worked from nature but from classical prototypes which in the course of repeated copying became quite unrecognizable.”

– Erwin Panofsky in a 1952 letter to Wasson excerpted in Soma, pp. 179-180

Note the ellipses, where Wasson omitted Panofsky’s recommendation of Brinckmann’s book; Wasson’s book SOMA shows only ellipses here, and Brinckmann’s name doesn’t appear in SOMA.

Did the history artists — I mean, the art historians — in fact discuss and debate the question of mushroom trees in Christian art?

Where is that debate recorded? What was the argument, or storytelling narrative, for those who asserted that the mushrooms mean psychoactive mushrooms?

What are some citations so we can learn how Panofsky’s storytellers (the art historians) wrote this narrative, after a 2-sided debate between the two positions? At what conference did these experts on mycology and mythology in art present their debate?

The Missing Book Citation to Substantiate the Claim That Art Historians Discussed Mushroom Trees in Christian Art

Brown’s article’s photograph of Panofsky’s letter fills-in that ellipses, providing a book citation for where to see the (otherwise vaguely alleged) investigation of mushroom trees by art historians.

For clarity, I here break out the restored text as a separate paragraph:

“The plant in this fresco has nothing whatever to do with mushrooms, and the similarity with Amanita muscaria is purely fortuitous. The Plaincourault fresco is only one example – and, since the style is provincial, a particularly deceptive one – of a conventionalized tree type, prevalent in Romanesque and early Gothic art, which art historians actually refer to as a ‘mushroom tree’ or in German, Pilzbaum. It comes about by the gradual schematization of the impressionistically rendered Italian pine tree in Roman and early Christian painting, and there are hundreds of instances exemplifying this development – unknown of course to mycologists.

If you are interested, I recommend a little book by A. E. Brinckmann, Die Baumdarstellung im Mittelalter (or something like it), where the process is described in detail. Just to show what I mean, I enclose two specimens: a miniature of ca. 990 which shows the inception of the process, viz., the gradual hardening of the pine into a mushroom-like shape, and a glass painting of the thirteenth century, that is to say about a century later than your fresco, which shows an even more emphatic schematization of the mushroom-like crown.

What the mycologists have overlooked is that the medieval artists hardly ever worked from nature but from classical prototypes which in the course of repeated copying became quite unrecognizable.”

– Transcribed from the photograph of Panofsky’s letter in Figure 2 (in Brown’s article): Letter of Erwin Panofsky to R. Gordon Wasson, May 2, 1952. Wasson Archives, Harvard University Herbarium, Cambridge, Mass. Page 145.

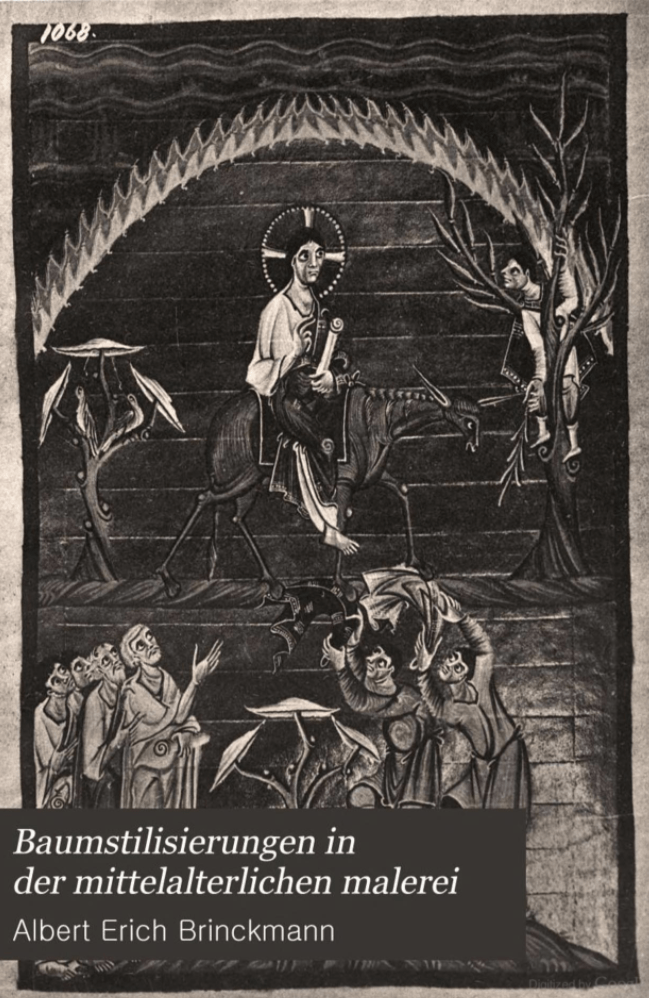

Brinckmann’s Book “Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings”

Here is the art historians’ mushroom-trees book which Wasson omitted from his reproduction of Panofsky’s letter in SOMA. This book is the alleged forum in which art historians have already discussed, and allegedly resoundingly dismissed, mushrooms in Christian art.

Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen Malerei

(Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings)

Albert Erich Brinckmann

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/mode/2up

http://amzn.com/3957383749

“Look inside” shows most of the 9 plates; Archive.org shows all.

Description from Amazon, translated:

“The art historian Albert Erich Brinckmann presents in this volume an overview of the different forms of tree stylization in painting. For this purpose, he looks at early Christian Italian works, Byzantine and Carolingian art. Illustrated with numerous illustrations on nine plates. Unchanged reprint of the long-out original edition of 1906.”

Publisher: Vero Verlag GmbH & Co.KG (February 15, 2014)

Brinckmann, Mushroom Trees, & Asymmetrical Branching

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2020/12/11/brinckmann-mushroom-trees-asymmetrical-branching/

includes all the plates, my commentary, and partial translation to English

The entire book at Archive.org:

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/mode/2up

The plates are shown at the end: 6 plates with some 10 plant schematizations each, and 3 plates with 4-5 works of art:

o Jesus riding a donkey (same as cover)

o 2-in-1: Vegetation + small rearing horse

o a) Eden tree, b) reclining/tree/horse

An English translation of this book would help, to check Wasson and Panofsky’s claim that art historians have already considered and soundly, justifiably concluded, against the well-argued countering view, that mushroom trees in Christian art don’t represent psychoactive mushrooms.

Why did Wasson Omit Mention of Brinkmann’s Book and Panofsky’s Two Specimens?

In his book SOMA (and other publications), why did Wasson not publish a citation of Brinckmann’s book which Panofsky recommended to him?

Along with the letter, Panofsky sent Wasson two specimens of mushroom trees in art, maybe photostats, which Wasson doesn’t mention in SOMA or other writings:

- “a miniature of ca. 990 which shows the inception of the process, viz., the gradual hardening of the pine into a mushroom-like shape”

- “a glass painting of the thirteenth century, that is to say about a century later than your [Plaincourault] fresco, which shows an even more emphatic schematization of the mushroom-like crown.”

Verdict: Wasson Censored Mushrooms from Christian Art, in Resisting Allegro’s 4-pronged Discrediting of Christianity

Did Wasson, banker for the Vatican, who had private meetings with the Pope, censor mushrooms from Christianity? Wasson was fighting a religious battle, or a 4-front war, against Allegro’s book which sought to discredit Christianity.

Wasson should have been interested in Brinckmann’s book; he should have read it, and cited it, either in SOMA or in a later publication.

Wasson cannot be taken seriously as a good-faith, sincere scholar of mushrooms, because he actively omitted mention of Brinckmann in SOMA and his other writings about mushrooms in religion, and omitted mention of the two specimens which Panofsky included with the first letter.

Given the significant time that Wasson spent “debating” Allegro about the Plaincourault fresco (though with no actual engagement), it is not believable, that Wasson saw fit to never mention Brinckmann’s book which Panofsky recommended to him, or the two specimens Panofsky attached.

Wasson’s functional role was to reduce, head-off, and avert the world’s curiosity about mushrooms in Christian art, not to encourage curiosity about the contention.

Wasson actively, deliberately omitted mentioning Brinckmann’s book, and that is inexplicable and inexcusable for a reputedly bold, curious, pioneering scholar of mushrooms in religion — inexplicable except for a conflict of interest: he was banker for the Vatican and had private meetings with the Pope.

It appears that Wasson averted attention from mushrooms in Christianity, to protect the status quo, against Allegro’s 4-pronged attempt to discredit Christianity.

Why didn’t Wasson tell people about the Brinckmann book? Why didn’t Hatsis show people his mushroom-tree research, or at minimum, summarize his arguments, in his book where that’s the most relevant topic of all? What’s with all the caginess and censorship of mushrooms in Christian art?

Dis-entangling the “Mushrooms in Christianity” question from Other Battles

For context, we have to understand Wasson’s extreme position against mushrooms in Christian art as pushing back against Allegro’s extreme positions, in a multi-front religious war. Allegro sought to discredit Christianity, by defaming it as a mushroom cult and a fertility cult based on a fictitious founder-figure.

The Plaincourault fresco was only one of four distinct vectors of attack to discredit Christianity, in Allegro’s book The Sacred Mushroom & the Cross.

To think, debate, and judge clearly about the specific, well-scoped topic of mushrooms in Christianity, and get past the roadblock of the Allegro/Wasson mono-focus fixation on debating “Secret Amanita Cult”, we must dis-entangle the questions that Allegro jumbled together:

- A secret Amanita cult in early Christianity.

- A fertility cult in early Christianity.

- The ahistoricity of Jesus.

- Mushrooms throughout Christian history – Allegro treated this most-important question as an afterthought, by including the Plaincourault fresco without any explanatory discussion of how it relates to his main 3 contentions.

The particular question of mushrooms in Christian art became entangled, thanks to Allegro and to Wasson’s pushback, with far-flung arguments about Jesus’ ahistoricity (an entire realm of scholarship and argumentation on its own), and even further afield in my view, fertility cult practices.

This entanglement of some four incendiary contentious topics, which we can squarely blame on Allegro’s Christianity-discrediting strategy, helps explain Wasson’s inexcusable censoring of Brinckmann’s book (along with Panofsky’s specimens).

Argument Through Asserting One Explanatory Framework Without Counter-argument

We have here, a conclusion, a 1-sided, just-so-story told by Panofsky’s history artists, not a debate laying out the well-formed arguments on both sides, with pros and cons to make a weighted, considered decision. How was this explanatory paradigm selected by running tests and weighing evidence?

We have the verdict and the storytelling of the allegedly winning narrative — but where is the 2-sided weighing of the two positions, the counter-narrative, the alternative explanation and arguments?

Congratulations: You managed to weave and assemble a story, an explanation framework — but what is the best case that the other side can make? That is not presented.

We’re only given a totally asymmetrical, lopsided, 1-sided argument. Panofsky, like Wasson, Letcher, and Hatsis, just presents an empty “argument from assertion”, an argument from authority.

“This is the correct interpretation, because we formulated an explanatory story to support that this is the correct interpretation.

“The shape is like a mushroom and a tree, therefore it must mean a tree and not a mushroom, because we say so; because that is the story narrative that we assert.”

See also the sections near “Panofsky Argument is Anti-Entheogen Apologetics, Lacking Compellingness” in my article Wasson and Allegro on the Tree of Knowledge as Amanita:

http://www.egodeath.com/WassonEdenTree.htm#_Toc135889217

For example, I wrote:

“Given that Wasson bandied-about this Panofsky excerpt for at least 17 years (1953-1970), and criticized Allegro for not accepting it, it’s remarkable that in Soma, the letters to the Times, or the letter to Allegro, Wasson didn’t go to the trouble of providing citations of the eminent art historians’ published studies on Pilzbaum. These would need to be studies that convincingly show why the mushroom-and-tree interpretation is surely wrong – studies that would need to convince those who are not already convinced or too-easily convinced.”

Defining 3 Positions about Mushrooms in Christian Art & Historical Practice

Incommensurable Paradigms: the Minimal, Moderate, and Maximal Mushroom Theories

The problem of “incommensurable paradigms”: How do we adjudicate between the 3 positions, explanatory frameworks, storytelling narratives, or just-so stories, to explain or explain-away mushrooms in Christian art?

Summary of the 3 competing explanatory frameworks:

1. Mushroom trees mean trees, not mushrooms.

Advocates: Panofsky/Wasson/Letcher/Hatsis.

The Minimal mushroom theory of Christianity.

Often associated with the broader Minimal entheogen theory of religion (“mystic experiencing is almost never drug-induced, in our religious history”).

2. Mushroom trees mean Secret Amanita Christian cult.

Advocates: Allegro/Irvin/Rush/Ruck.

The Moderate mushroom theory of Christianity.

“Mushrooms have occasionally been used in the guise of Christian practice, but but only in rare, abnormal, deviant, heretical, exceptional instances”.

Often associated with the broader Moderate entheogen theory of religion (“mystic experiencing has occasionally been drug-induced in our religious history, but only in rare, abnormal, deviant, heretical, exceptional instances.”)

3. Mushroom trees mean psychoactive mushrooms.

Advocates: Hoffman/Brown.

The Maximal mushroom theory of Christianity.

Associated with the broader Maximal entheogen theory of religion (“the main, normal, primary wellspring and source of religious experiencing, throughout world religious history, including Christianity, is entheogens”).

Mushrooms in religious art simultaneously represent:

o The concomitant mystic altered state induced through any visionary plants.

o Transcendent Knowledge (gnosis) produced by the altered state, regarding personal control and time.

o The language of religious mythology (mythemes) as description of the aforementioned items through analogy and metaphor.

Minimal/Moderate/Maximal theories of various issues

There are many ways to scope this field of debate. For example, we can define a “Minimal”, “Moderate”, and “Maximal” version of any of the following attempted explanatory frameworks (or “positions”, or “theories”):

The Minimal, Moderate, and Maximal theory of:

- secret Amanita in Christianity — over-debated, inherently limited to two positions/camps: Minimal vs. Moderate.

- psychoactive mushrooms in Christian art — under-debated, and too conflated with the previous debate. Enables all 3 positions: Minimal, Moderate, Maximal.

- psychoactives in Christianity

- psychoactive mushrooms in Christian artifacts (text & art)

- many other wording variants, scoped distinctly

A Dead-End Debate: “Secret Amanita Christian Cult” vs. “No Mushrooms in Christianity”

The Wasson vs. Allegro debate is irrelevant and needs to die, replaced by more appropriate, relevant questions and positions.

The Egodeath theory‘s Maximal Entheogen Theory of Religion replaces the entire, off-base “Wasson vs. Allegro” debate on whether there was, or wasn’t, a “Secret Christian Amanita Cult”.

In particular, more specifically, the Egodeath theory’s Maximal mushroom Theory of Christianity replaces the irrelevant and overplayed “Wasson vs. Allegro” debate.

The “Wasson vs. Allegro” debate by this time is doing more to block progress than contribute insight, because both sides of that debate limit the conceptual possibilities to: either there was a “Secret Christian Amanita Cult”, or there were no mushrooms in Christianity.

Eject your endless-loop 8-track tape, and join the 21st-Century discussion.

As I exclaimed in my 2006 Plaincourault article, the debate over that one over-specific, “Secret Amanita” scenario prevents asking the far more relevant question:

To what extent visionary plants in Christian history?

Since 1968, through 2018, there’s been an overly loud argument exclusively between the Minimal vs. the Moderate Entheogen theories of religion. But distinct from those two positions and that 2-way argument, there is a 3rd, independent position, the Maximal Entheogen theory of religion.

Hatsis pretends to be the gateway, Maximal entheogen theory (“A comprehensive look at the long tradition of psychedelic magic and religion in Western Civilization“), but he’s really just the gatekeeper, Moderate entheogen theory.

Who cares if there was or wasn’t, specifically, a “Secret Christian Amanita Cult”? Why should we care whether that particular, specific scenario was the case? There’s no justification provided for fixating on that particular debate.

The actual, relevant question is, instead, against Hatsis and his club:

To what extent were psychedelics used throughout Christian history, as evidenced by art and text?

To what extent are mushrooms present in Christian art?

What are the arguments in favor of reading mushroom images as “mushrooms as well as trees”, as opposed to “trees but not mushrooms”? That is:

o What are the arguments in favor of reading mushroom images as “mushrooms as well as trees“?

o What are the arguments in favor of reading mushroom images as “trees but not mushrooms“?

Don’t be like Panofsky’s art historians and lopsidedly only assert one view and present only the arguments in favor of that view; you must also present the counter-arguments, as well.

Why would you not read ‘mushroom’ as a mystic-state inducing, psychoactive mushroom, GIVEN THAT THE CONTEXT IS RELIGIOUS MYTHOLOGICAL ARTISTIC REPRESENTATION?

What do Panofsky’s art historians have to say in answer to that?

Forget the “secret Amanita” question; the important question is not the “secret Amanita” question.

Stop placing the “secret Amanita” question as the central touchpoint of contention; stop assuming that “the secret Amanita” question is an important or worthwhile formulation to contend over. It is not a helpful guiding debate.

These 3 positions below are not meant to be precise descriptions of what each author argues, but rather, to provide 3 stereotyped, possibly simplified, positions for the purpose of analysis.

1. No Mushrooms in Christianity (Brinckmann/ Panofsky/ Wasson/ Letcher/ Hatsis); the Minimal mushroom theory of Christianity

If a symbol looks like mushrooms and something else, it means something else.

A symbol has one meaning: either mushroom or something else (tree, grape bunch, nail for crucifixion).

Artists didn’t understand or recognize psychoactive mushrooms. The Plaincourault painter didn’t realize the mushroom theme he painted, but the snake was associated with mushrooms, which the painter had no inkling of.

If you’re reading this argument, You may think the words are going wrong

But they’re not; He just wrote it like that

When you study late at night, You may feel the words are not quite right

But they are; He just wrote them himself

Wasson’s “No Inkling” passage

2. Secret Amanita Christian Cult (Allegro/Irvin/Rush/Ruck); the Moderate mushroom theory of Christianity

The color Red means Amanita mushrooms ingested.

Secret cult passing on their tradition across time and space.

Secret means the cult and practice.

3. Mushrooms Central in Christianity (Hoffman/Brown); the Maximal mushroom theory of Christianity

Any mushroom in religious art means Psilocybe or sometimes Amanita, which stands for any visionary plant, including Scopalamine.

Mushrooms are everywhere in religious art. If an element in art at all resembles a mushroom shape, the author intended psychoactive mushrooms and the audience recognized it as psychoactive mushrooms.

Mushrooms are widespread in religious art, such as cathedral windows, in all eras from archaic to late-modern. Religious artists depict psychoactive mushrooms.

Mushroom means visionary plants and the mystic altered state (loose cognitive association binding) and the Transcendent Knowledge that that experiential state produces — transformation of the mental worldmodel from Possibilism to Eternalism, as a model of control and time and possibility.

Whether an Author Is Minimal, Moderate, or Maximal, Depends on How Broad the Particular Debate

Regarding the narrow topic of the vial in the Saint Walburga tapestry, Brown is Minimal or Moderate, not Maximal. Irvin is Maximal regarding this vial. I’m Maximal on this narrow topic (and most topics).

Here’s a reversal of two authors being Minimal vs. Maximal:

Regarding the broad theory of mushrooms in Christian art:

o Irvin is Moderate (“mushrooms in Christianity mean Secret Amanita Christian Cult”).

o Brown is Maximal (“mushroom shapes in Christian art represent psychoactive mushrooms”)

Regarding the narrow instance of the Saint Walburga tapestry vial, they flip:

o Irvin is Maximal (“the object represents Amanita”)

o Brown is Minimal (“the object represents a vial but not Amanita”).

On the broad but still specific topic of mushrooms in Christian art, Brown is Maximal, except for the vial instance, where Brown is uncharacteristically Moderate in the course of presenting the good idea of a balance in-between “those who see mushrooms everywhere” vs. “nowhere”.

“Hatsis has performed a valuable service in calling attention to the excessive enthusiasm of some researchers. Unfortunately, he makes the same mistake – favoring dogmatism over fact – but in the opposite direction. When it comes to the study of entheogens in Christian art, Irvin and Rush tend to see mushrooms “everywhere,” whereas Hatsis cannot see mushrooms “anywhere.”” — Entheogens in Christian art: Wasson, Allegro, and the Psychedelic Gospels, Brown & Brown, p. 158

“… it is important not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. In this case, the bathwater contains the spurious, discredited claims Allegro made about the ahistoricity of Jesus, and the origins of Christianity as a mushroom-sex cult. The baby refers to Allegro’ s thesis that visionary plants had been widely used in Western culture and religion throughout the ages including the mystical experiences of early Christianity. According to [Michael] Hoffman …, this view is supported in one form or another by a variety of entheogen scholars…” — Entheogens in Christian art: Wasson, Allegro, and the Psychedelic Gospels, Brown & Brown, p. 159

Brown’s implicit category-scheme in that section of the article is comparable to my concept of Minimal/Moderate/Maximal versions of a given entheogen theory.

On folds in clothing, I’m closer to Maximal than Moderate. Many folds depict mushrooms, per John Rush.

On the narrow question of Amanita, Irvin is Maximal – he sees Amanita at every opportunity. Red means Amanita. But, this very fixation on Amanita, and especially his camp’s fixation on “Secret Amanita Christian Cult”, pushes Irvin to be only Moderate, regarding Psilocybe and Entheogens generally, throughout Christian history.

Positions on the Ahistoricity of Religious Founder Figures

Regarding the ahistoricity of religious founder figures:

o I’m Maximal (“generally, religious founder figures are ahistorical constructions”).

o Brown is Minimal (“the … discredited claims Allegro made about the ahistoricity of Jesus, …”).

Discredited? Richard Carrier, and his camp of intensive scholars on that topic, begs to differ.

Jesus from Outer Space: What the Earliest Christians Really Believed about Christ

Richard Carrier, October 20, 2020

http://amzn.com/1634311949

Due to the reception history of Allegro’s book The Sacred Mushroom & the Cross (1970), and the fixation on the irrelevant debate of “either Secret Amanita Christian Cult, or else No Mushrooms in Christianity”, it is impossible to make progress on the entheogen theory of religion, or the narrower, mushroom theory of Christianity, without dealing with the obstruction known as the Wasson/Allegro debate.

That’s why I had to write my exhaustive, formal Plaincourault article for publication in Robert Price’s Journal of Higher Criticism:

Wasson and Allegro on the Tree of Knowledge as Amanita

http://www.egodeath.com/WassonEdenTree.htm

I led the way for early 21st-Century Radical Critics such as Acharya S & Robert Price (who I corresponded with) to become Maximal on the topic of the ahistoricity of religious founder figures.

My webpages and articles on the ahistoricity of religious founder figures in general were published before some of the ahistoricity books by Acharya & Price (such as the ahistoricity of Paul, Peter, and the other apostles).

I disagree with many aspects and assumptions of Allegro’s story that “the original Christian cult used Amanita and held that Jesus was Amanita, and later Christians forgot that and only thought of Jesus as a man, not Amanita”.

An Attempted Argument for the Moderate Mushroom Theory of Christianity: The Vial that Looks Like Amanita

Brown’s Passages About the Vial in the Saint Walburga Tapestry

On page 153 of the book The Psychedelic Gospels, Brown writes:

“The caption under a photo of the tapestry [from Irvin’s book The Holy Mushroom] … reads,

“St. Valburga is depicted holding a distinct Amanita muscaria in its young bulbous state of development, complete with white spots – the key to ‘feast’ celebrations. The background [of the tapestry, behind the saint] is red with white floral decorations.” — Irvin’s caption

Brown continues:

“Looking closely at the photo, Julie disagreed with this description.

“Jer,” she said, calling me over to the hotel room window to examine the photo in the light. “Look closely, there at the bottom. That’s a straight edge, not the round bulb of an Amanita. And furthermore, this white “bulb” is serrated all over with regular grooves. That’s not a mushroom she’s carrying, but a white vial with a red top probably holding her healing oil.”

Brown’s article also discusses the Saint Walburga tapestry:

“To cite one example, in plate 32 of The Holy Mushroom, Irvin describes St. Walburga as “holding a distinct Amanita muscaria in its young, bulbous state of development, complete with white spots” (p. 136). … we realized that St. Walburga was not holding a mushroom but a vial containing healing ointment, as confirmed in numerous other artworks and accounts of her life.” – Brown & Brown, Entheogens in Christian art, p. 157 lower right

Brown Commits the Single-Meaning Fallacy

Brown & Brown themselves commit the single-meaning fallacy, arguing that the object held by Saint Walburga is a vial, and therefore cannot also visually represent an Amanita. Brown argues that the object has a flat (straight edge) bottom, so it is a vial and therefore cannot also represent an Amanita.

Arguing that an item represents one thing and therefore cannot represent another item, even if the other item is isomorphic, is the single-meaning fallacy.

Article:

Entheogens in Christian art: Wasson, Allegro, and the Psychedelic Gospels

Brown & Brown, p. 158 upper left image, “Tapestry of Saint Walburga”

https://akjournals.com/view/journals/2054/3/2/article-p142.xml

Vial held by Saint Walburga, close-up of the image on p. 159

Brown argues that the item has serrations and therefore cannot be an Amanita. The serrations which Julie Brown points out as evidence against Amanita can serve as evidence for Amanita.

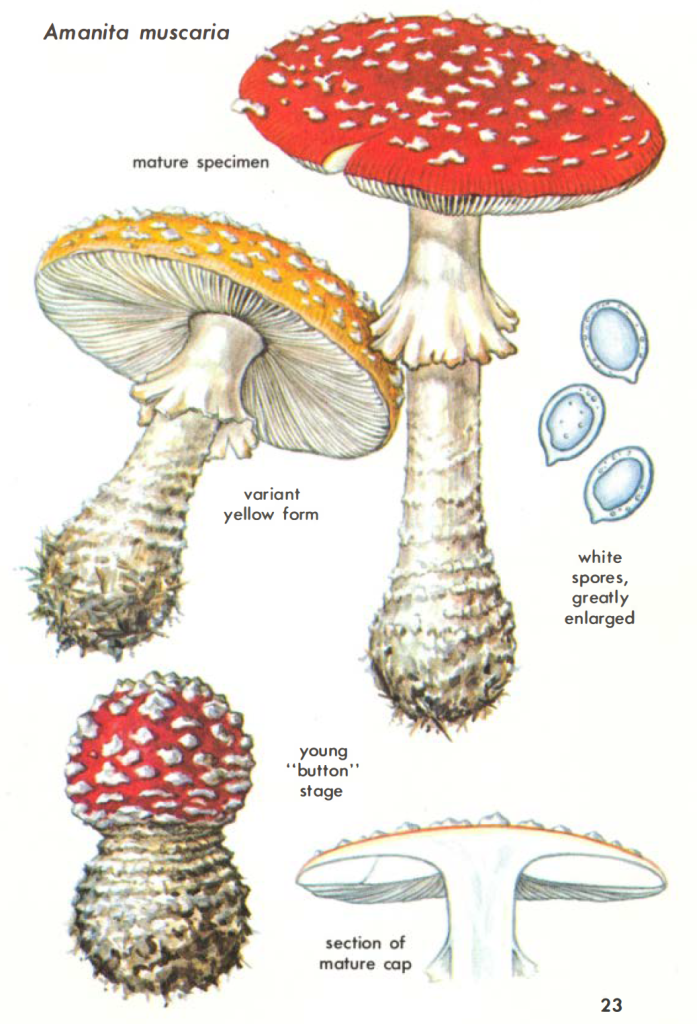

Amanita sometimes has a distinctive leafy ribbed base, as one of its interesting forms, as shown in the photographs below. Amanita enables flexible depiction in art, because of its varied shapes, textures, and colors – that’s part of the otherworldly, shapeshifting magic and appeal of the Amanita, as the book Strange Fruit demonstrates.

1. Irvin – “It’s an Amanita.”

2. Brown – “It’s a vial, not an Amanita.”

3. Hoffman – “It’s a vial that’s designed to look like an Amanita.”

An Amanita with a leafy serrated base, like examples in the book Strange Fruit. Photograph from a Web search.

“Very baby fly agaric”, by Dr Steven Murray

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/310537336784234578/

A serrated base of an Amanita that’s in a state between egg shape and dumbbell shape, following the lifecycle descriptions in the book Strange Fruit. Photograph from a Web search.

From the book Hallucinogenic Plants (A Golden Book), by Richard Evans Schultes, 1976 (0th Edition of Plants of the Gods)

Amanita-styled salt shaker, with flat (straight edge) base, demonstrating that a container with a flat base can represent an Amanita. From a Web search.

Amanita-styled clear glass container, with flat (straight edge) base, demonstrating that a container with a flat base can represent an Amanita, to good aesthetic effect. This clear vessel highlights that it’s a container. From a Web search.

Amanita-styled white glass container, with round sides and flat (straight edge) base, demonstrating that the base of a vessel can be broader than the cap, while still reading as Amanita. From a Web search.

An Amanita cap on a white cup to contain tea, with rounded sides and a flat (straight edge) bottom, designed to look like an Amanita. From a Web search.

A hermetic seal Amanita-cap lid with a broad white container base with a flat (straight edge) bottom. From a Web search.

Web searches for Amanita:

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=amanita+container

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=amanita+salt+shaker

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=amanita+bottle

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=amanita+egg

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=baby+amanita

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=amanita+lifecycle

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=amanita+bulb

Book:

Strange Fruit: Alchemy, Religion and Magical Foods: A Speculative History (= 1st Ed., 1995)

Magic Mushrooms in Religion and Alchemy (= 2nd Ed., 2002)

http://amzn.com/0892819979

Clark Heinrich

Brown’s Example of Mis-identification Backfires

Brown uses a good strategy, of constructing two bracketing categories, like “those who see mushrooms nowhere” and “those who see mushrooms everywhere”.

In the effort to strike a pose of being fair and centered, Brown begins the section against “those who see mushrooms everywhere” by discussing the image in a Tapestry of Saint Walburga which looks like a baby Amanita with small cap and large oval body, but with a flat base for a vial.

This section of Brown’s article, “Overenthusiasm by ardent advocates“, tries to leverage an actually reasonable and justifiable example of seeing an Amanita despiction as “overenthusiasm”. But above, I demonstrated that this vial example is actually a counter-example that works against their case, because Amanita sometimes has a distinctive serrated base, and because Amanita-styled containers have a flat base.

Brown’s choice of this vial example to make the case against the Amanita identification backfires and instead shows that the Maximal theory “over”-enthusiastic advocates may well be closer to the truth than Brown, who here strikes a pose advocating a Moderate theory of interpreting mushrooms in art.

The held object in the tapestry resembles an early-lifecycle Amanita; Saint Walburga is holding a vial with a flat bottom, that is designed to look like an Amanita.

Beware the “argument-from-single-meaning” fallacy. Saint Walburga is known to hold a vial, and the vial can be styled to look like an early-stage Amanita.

‘Cause you know sometimes words have two meanings.

Brown’s Committee for Judging Mushrooms in Christian Art

Is there a gallery of Christian mushroom art, so people can make their own decision on reading the art, instead of some self-appointed “authority” issuing pronouncements as if from on high? It’s time to let the art speak for itself, instead of would-be gatekeepers trying to obstruct and silence it.

Brown & Brown are correct: start a project to gather all the images, and then debate. But what’s going to stop their Committee from crashing and burning on the rock of incommensurable interpretive paradigms?

It is impossible to adjudicate between you, who say “Is not!“, and me, who say “Is too!“, other than speculation about, or somehow measuring, which explanatory framework is more successful and powerful.

Brown proposes to set up a university Committee to “properly adjudicate” so now they’ll be able to look at a mushroom image and know whether to read it as Mushroom or Not Mushroom.

Never mind the problem of incommensurable paradigms & vested interests. I confidently predict that they will get the interpretive results that they are committed to coming up with. Because the authorized Art Historians have a story to explain the images. (Others’, competing explanatory stories don’t count.)

Brown & Brown call for creating a Committee, which would do more careful, more accurate description of items shown in art, and would look at many photographs of Amanita and other visionary plants.

Such a committee could also get proper, clear copies of art, instead of the blurry images from John Rush’s book. I applaud Rush’s resourcefulness and contributions to interpretation, but was disappointed by the inadequate clarity of many of the images.

Hatsis Is Worth Limited Critique

Hatsis is a mixed bag, like scholars in general. Some of his argumentation errors are not worth refutation. It’s more profitable to write up what is the case, then do a point-by-point rebuttal of each of Hatsis’ arguments.

Hatsis mostly seems to commit a few fallacies and go wild with those:

o The “Amanita primacy” fallacy — is that the fault of Irvin/Rush, tho? The bad dynamic is the interaction of Hatsis against the Irvin/Rush position of circa 2010.

o The “single-meaning” fallacy — “This might be a shroom, but I discovered a better interpretation: it’s a [nail|tree] — therefore, it’s not a shroom!!” (facepalm) This basic error violates Poetry 101.

o The “debunk the secret Amanita cult” fallacy — Hatsis intensively uses phrases, he spits phrases like “the Secret Christian Amanita Cult” – he thinks he’s battling a very specific gang of advocates, with a narrow, specific name. He’s battling a windmill that’s maybe only 50% overlap with the Egodeath theory’s interpretive approach.

Contributions from Hatsis Despite Himself

There are many good fragments of discussion & images from Irvin, Rush, and Hatsis.

Brown debated Hatsis, which is good for moving research forward.

Hatsis is applying valuable scholarship to the images and storylines. The more that such debates are constructively driven, the more progress. There’s potential progress here.

Scholarship is like that: a mix of folly and insights, bad argumentation like Wasson’s book SOMA both critiques, and itself commits.

There are many fragments of value in Hatsis’ writings; good pictures. He sometimes presents the best mushroom-trees to wave-aside.

It’s been hard to keep the present article short and organized as originally expected, because it turned out that Hatsis’ arguments are omitted from his book, and are scattered instead in articles, one of which I can’t find again online. I posted critique on his 2017 articles when they were new, at the Egodeath Yahoo Group.

Hatsis’ book only contains an unsubstantiated sweeping denial of mushrooms in Christian art, stating the title of two of his articles, which aren’t in the book — not even as summarized arguments.

I discovered that that to review Hatsis’ arguments against mushrooms in Christian art, I have to not only assess this book, but also, much more so, his online articles (again).

Hatsis’ book contributes a lot to entheogen scholarship in Western religious history. I’m focused here on Hatsis’ position regarding Amanita, Psilocybe, and visionary plants in Christian art.

“easily explained away through sound, tried-and-true historical criteria”

Emptier words have never been said.

p. 139: “The supposed mushrooms that appear in Christian art are easily explained away through sound, tried-and-true historical criteria, which those who still support the theory (in one variety or another) have simply not considered.”

This writer in this book doesn’t even bother to be up front summarizing what his argument is, while insulting the reader as “have simply not considered”. Unscholarly and a ripoff.

It’s a cheap evasive psych-out move, not persuasion through scholarship. Hatsis has by no means demonstrated, in this book or at his psychedelicwitch website, that Christian mushrooms are “easily explained away through sound, tried-and-true historical criteria“.

Why didn’t he put his unimpeachable, definitive, rock-solid, summarized arguments in the book that he charges money for, to back up his massive, centrally relevant claim, that “The supposed mushrooms that appear in Christian art are easily explained away“?

“sound, tried-and-true historical criteria” — what a JOKE! All Hatsis has is baseless, smug assertions, which he doesn’t even have the integrity to include in his book.

It’s angering that after I paid money for the book, he makes a massive statement in the book, insults as “have not considered” those who disagree, and then just gives the name of his online articles to back up his vague dismissal of all mushrooms in Christian art.

It’s maddening that now I have to critique not only the book, but even more so, two online articles that the book so casually uses as its sole foundation for the massive, smug, total, sweeping denial of mushrooms in Christian art.

Hatsis’ book only contains vague arm-waving assertions, delivered with smugness; the articles that contain Hatsis’ arguments (and mushroom tree art, omitted or censored from the book), are at Hatsis’ site.

His site is the “psychedelicwitch” domain name, now redirected to his renamed, “psychedelichistorian” domain name.

Then, after you find his articles by using Web search (because they are not linked from his home page), those online articles grant that the images might be mushrooms, but that doesn’t mean they are psychoactive mushrooms.

WEAK! So much for his slam-dunk argument that is too sound to bother putting it in the printed book.

Wasson and Allegro had entanglements and conflicts of interests that distorted and confused the question of mushrooms in Christianity. Hatsis lets his advocacy of Mandrake (and his strategy of self-promotion by straining to taunt and discredit Irvin) discourage recognizing mushrooms in Christian art.

Search Hit Counts on various plants in the book

Search hits, says it all, for this book’s single-plant fallacy: Hatsis the witch pushes Mandrake, ignores Psilocybe in Christianity, and (in his articles) obsesses on rejecting “secret Amanita”.

mushroom 123

opium 121

cannabis 111

mandrake 78

secret 53

amanita 50

Brown 25

henbane 13

Allegro 12

psilocybin 5

tree of knowledge 5

tree of knowledge of Good and Evil 3

opiate(s) 3

psilocybe 1

wormwood 1

Irvin 0 <– omitted, like Hatsis’ arguments for his massive, centrally relevant claim of “no mushrooms in Christian art” are omitted – even though ‘mushroom’ is the top hit

laudanum 0

scopolamine 0

datura 0

thornapple 0

Free-form Comments About Hatsis’ Book

I’m also interested in visionary plants in Greek religion and Western Esotericism.

Hatsis is not focused on Psilocybe or Christian art. He’s focused on Mandrake and texts, against a very narrow theory of Amanita in Christianity.

To characterize his book (regarding the question I’m focused on), my revealing version of his title is, per the single-plant fallacy:

Mandrake, not Amanita, Is the Christian Entheogen, by Witch Hatsis

Page numbers for Hatsis’ book in the present article are for Kindle (348pp), not paperback (288pp).

Like Andy Letcher, Hatsis’ angle is to counter Allegro, setting up “Allegro and the followers of Allegro’s theory” as the bad guy to defeat.

Hatsis is aiming at a target that’s not as important as he acts. Some people do act as if Allegro is highly important, along with some Amanita-focused theory of Christianity, so I wouldn’t quite say Letcher & Hatsis are just titling at windmills.

Irvin does emphasize Amanita. Hatsis isn’t just broadly dismissing that mushrooms are in Christian art; Hatsis is specifically choosing to rebut and focus on Irvin’s theory, which is Amanita-focused.

Maybe Irvin & Rush focus on Amanita. This may be a debate between two camps, which aren’t focused on my position, which is neutral regarding Amanita.

Letcher & Hatsis give undue focus to one particular conception of the role of Amanita in Christian art, in relation to Christians ingesting Amanita.

Like Letcher, Hatsis is fixated on Allegro, as if Allegro is the most important touchpoint of contention.

Jan Irvin was an Allegro cheeerleader, whereas, unlike Irvin, I always emphasized the limits of Allegro. I consider Allegro as of no outstanding import as an entheogen historian/scholar.

My position is that Christian art shows Amanita (as well as Psilocybe and mandrake), and Amanita in Christian art means the use of visionary plants to induce the loose cognitive state, producing Transcendent Knowledge. Mine is a substantially different position than the position which Letcher & Hatsis fixate on debunking.

page 183: “rites of Dionysus … a psychedelic mushroom (psilocybin or otherwise) was almost certainly added to the wine.”

A key page is 140, which is poorly, vaguely worded: Why are such writers incapable of writing in plain statements on this topic? Every sentence is filled with completely unclear phrases. What exactly are you saying is the case? —

“Now, some of these scholars are correct to a certain degree; Christians did experiment with theogens. They are also correct in thinking that these Christian mystery traditions are glosses of ancient Hebraic literature like the story of the Fall in Genesis. But the occult lessons of the Fall have nothing to do with the Tree of Knowledge. There is, in fact, no evidence that any Christian ever interpreted the forbidden fruit in such a way.

“Here is where the discipuli Allegrae and I part company. While they believe that the key Christian psychedelic mystery traditions rest in the forbidden fruit that Adam and Eve ate in the Garden, I hold a different opinion. There isn’t a shred of evidence to suggest that medieval artists secretly signified entheogens as the fruit by depicting the Amanita muscaria mushroom into art. There does exist, however, evidence for such psychedelic mystery traditions, buried in obscure literature long forgotten.”

Here, Hatsis conflates a particular art assertion (Amanita, not Psilocybe, in depictions of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, not in other art scenes), with the broad theory of mushrooms in Christian art. Does Hatsis say there are no mushrooms in Christian art? I say there are countless mushrooms in Christian art. He makes a huge show of contesting one, particular, narrow theory, while acting as if he’s debunking a very broad theory.

p. 139: “The supposed mushrooms that appear in Christian art are easily explained away through sound, tried-and-true historical criteria, which those who still support the theory (in one variety or another) have simply not considered.”

These criteria are self-evident, and you’re an idiot if you aren’t convinced by what I haven’t written here in this book you paid for. If you must have definitive proof, see my psychedelic witch site, which doesn’t link to the articles, that prove I’m right and you’re ignorant.

I can’t make heads or tails out of what Hatsis is saying, “The occult lessons of the Fall have nothing to do with the Tree of Knowledge.” What exactly are you denying & asserting? “There is … no evidence that any Christian ever interpreted the forbidden fruit in such a way.” In such what way?

“[whether] the key Christian psychedelic mystery traditions rest in the forbidden fruit that Adam and Eve ate in the Garden.” What is this supposed to mean, to assert & deny? —

“the key Christian psychedelic mystery traditions”

“rest in”

“the forbidden fruit that Adam and Eve ate in the Garden”

Answer a plain question:

Does Christian art depict mushrooms as the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil? I say yes; what exactly does Hatsis say?

Did Christians think of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil as all of the following:

o Visionary plants

o The state of consciousness produced by visionary plants

o The Transcendent Knowledge that results from that state of consciousness that is produced by visionary plants; the transformation of the mental worldmodel from Possibilism to Eternalism, as a model of control and time and possibility.

I say yes; what exactly does Hatsis say?

p 142 he narrowly defines the word ‘fruit’. In contrast, I define ‘fruit’ to mean any entheogen, the altered state from entheogens, and the knowledge which the altered state reveals. “The ‘fruit’ represented temptation and apostasy from God; all other modern interpretations resting in an Amanita muscaria Christian art conspiracy? Fruitless.”

The tree story in Genesis is extremely playful, overloaded with a play of multiple meanings, including two senses of ‘death’. It’s beyond Hatsis’ interpretation (p141, fruit = temptation); it’s challenging.

p172 a curious thing about writing is that the more clarifying qualifiers you add, the more confusing the result is. “Christian psychedelic mysteries … [I] demonstrate [that] orthodox traditions … have nothing to do with secretly painting Amanita muscaria mushrooms into medieval Christian art.” Try a simplest statement: Is Hatsis saying that Christianity lacks mushrooms in art? He quietly avoids that issue, that statement, that question.

Hatsis pretends that the broad question “Are there mushrooms in Christian art?” is the same as the narrow question “Are there secretly, Amanita, in medieval Christian art?” This is evasive, deceptive writing.

Imagine an infinitely narrow question, along the lines of:

“Do we have explicit, textual evidence, that there are secretly, Amanita mushrooms, in medieval Christian art which depicts the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of Good and Evil, and which was interpreted by the mainstream Christian church as the ‘fruit’ meaning ingesting Amanita, to have an intense mystic experience?”

Even if the answer to that infinitely narrow question is “No”, we have failed to address the simple question:

Are there mushrooms in Christian art?

If there are mushrooms in Christian art (which there are, in abundance), then the ‘fruit’ of the tree of the knowledge of Good and Evil, which does and does not cause death on that day, means entheogens and the altered state and Transcendent Knowledge.

The fruit of the tree of the knowledge of Good and Evil = mushrooms in Christian art = entheogens and the altered state and Transcendent Knowledge, including complex play and twists of ideas about “rebellion” and “punishment” and “expulsion through the garden gate”.

The great show of bluster from Letcher and Hatsis just serves to obscure that simple, sound, justified interpretive theory.

p. 91, Hatsis is plainly wrong and shows that he is unqualified to discuss art; he hasn’t examined many illustrations. “when ancient peoples depicted a mushroom they did so without ambiguity” What an absurdly over-broad and overconfident statement! He must have mind-reading ability. How can a scholar write “ancient peoples”? He makes a uselessly vague and broad, sweeping overgeneralization. Hatsis is the world’s worst guide to mushrooms in religious art.

There’s a flexible spectrum ranging from literal mushroom depiction to abstract shapes. We see in one art work, a range of grape clusters, ranging from mushroom shape to abstract.

Mytheme-Illiterate Hatsis Calls a Serpent-Basket a “Mixing Vat”

Hatsis fails to cover mushrooms in Greek art, in his book — a huge omission. Hatsis doesn’t mention Graves’ 1957 recognition of mushrooms as the basis of Greek religious mythology.

Hatsis is unqualified to cover Greek mythology. He mentions mushrooms as a hypothetical possibility once or twice, in the relevant chapter. Hatsis is an un-read outsider to the field of mushrooms in Greek religious mythology, and his commentary should be given the attention it deserves.

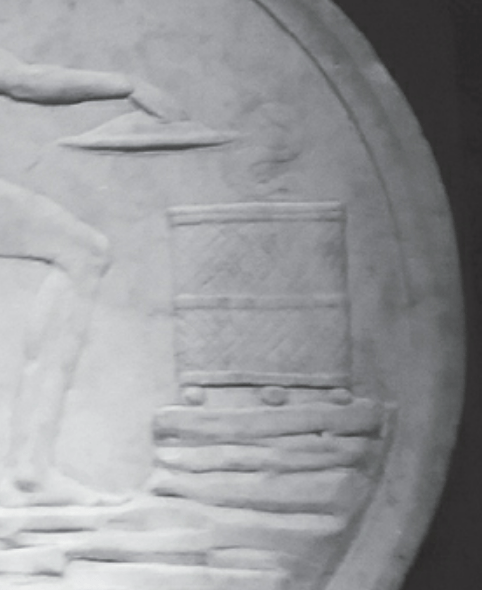

p. 92 – “oracle of the Dionysian shrine drank a mushroom wine … the hydria … In one scene, … what very much looks like a small mushroom; in the juxtaposed scene, … presenting a grape vine to the man, … add it to the mixing vat …” p. 93 “another rendition of this … scene seen on a plate … shows neither a mushroom nor opium … but rather a serpent”.

He goes on to discuss a plate. The plate is shown on the next page, with a wrong caption that says “mixing pharmaka into wine“, which is not appropriate for the basket (cista mystica) that’s shown.

The plate shown in Hatsis’ book, p.93. Hatsis’ incorrect-in-every-way caption: “Fig. 4.1 Sacred Marriage: ivy and wine. Bacchus mixing pharmaka (symbolized as the serpent) into wine.”

Article about images of basket (cista mystica):

https://ferrebeekeeper.wordpress.com/2012/06/08/cista-mystica/

Wikipedia Cista article shows a coin with snake emerging:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cista

serpent actually means block-universe worldline (snake in rock) which brings entheogens and loose cognition (the mystic altered state) and realization of Transcendent Knowledge. Hatsis commits the single-meaning fallacy, or single-aspect fallacy.

The large cylindrical object has cross-hatches and a lid. Hatsis doesn’t recognize the theme of uncovering the basket by removing the lid and revealing the hidden, occluded snake of the block-universe worldline, describing entheogen-induced experiencing.

I’m not going to waste my time here correcting his every incorrect word of mis-identification in this image. For my full mytheme-decoding of the above plate, find ‘basket’ in the weblog article:

Possibilism vs. Eternalism: Two Models of Time and Control

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2020/11/12/possibilism-vs-eternalism-2-models-of-time-and-control/

Aside: Say ‘use’, not ‘experiment’

I dislike the word ‘experiment‘, with its heavy affectation, its loaded, confusing, complex, negative, weak, and feeble connotations and stance of “I reject this and distance myself from it and disavow and minimize”; say, positively and simply and neutrally, ‘use‘.

“Joe used mushrooms” — Everyone can agree; it is the simplest, plainest statement of fact.

“Joe experimented with mushrooms” — What exactly are you claiming when you thus characterize his use of mushrooms?

/ end of free-form comments on the book

My Hypothesis

Rewrite this section, since Hatsis denies mushrooms in Christian art.

In 2017, Hatsis had a vague position that emphasized that Christianity was not based on entheogen use throughout its history, and especially that we do not have evidence for entheogen use throughout the history of normal proper Christianity.

Meanwhile, Park Street Press published the book by Brown & Brown, The Psychedelic Gospel.

When Hatsis contracted with Park Street Press, they helped him to become more specific about the “entheogenic Christian history” theory, to develop a positive and coherent, consistent narrative of entheogenic Christian history, so he did, at that time, contrasting with his less well-articulated 2017 Letcher-like dart-throwing against the entheogenic Christian history theory.

On page 201, Hatsis mentions “During my debate with Jerry Brown,” — so we see a good situation, of two Park Street Press authors debating the topic of Amanita in Christian history.

Park Street Press could not have one new author seeming to contradict another of their authors, with their books contradicting each other and cancelling each other out.

That’s my speculative hypothesis.

Any theory is likely to start out relatively incoherent, poorly articulated, and poorly evidenced (“Exactly what is it that you are denying, and asserting? You’re all over the place and contradicting yourself and moving the goalposts”), and end up more coherent, better and more consistently articulated, and well-evidenced.

Andy Letcher is the best example of this incoherence and failure to construct a positive, coherent, consistent, specific theory of what is the case, in his book Shrooms.

This is the sense in which the earlier, garbled, inconsistent, self-contradictory theory, is replaced by the later, clear theory.

Does 2018 Hatsis contradict 2017 Hatsis?

Rewrite this section, since Hatsis denies mushrooms in Christian art.

The instant question, the elephant that tramples immediately into the room: Is Hatsis consistent? Does he retract his previous denials of the great extent of entheogens throughout Christian history and religious mythology? Does this book contradict his previous, 2017 articles?

Where does Hatsis now stand on the spectrum, from minimal, to moderate, to my Maximal Entheogen Theory of Religion per the Egodeath theory? Does he continue to dismiss and belittle the evidence for entheogens throughout the heart of Christian history?

Was the publisher able to get him to conform and comply to the story which other entheogen scholars (eg Brown & Brown) need to continue to tell? Or is he committed to rejecting and de-legitimating as much evidence as possible? Is this a plot to censor entheogens from the heart of Christian history, sidelining that into abnormal and exceptional “gnostic Christian” othering & “Christian magic” heresy?

Given this hypothesis, my time is far better spent critiquing Hatsis’ formal 2018 book, than (as I did in Egodeath Yahoo Group posts, and comments at Cyb’s WordPress weblog) critiquing Hatsis’ less-formal, negatively toned articles & videos against Jan Irvin, which were (naturally) not thought-through or researched as well as the book.

For constructive entheogen scholarship, particularly regarding Greek religion & Christian historical practice, Hatsis should be judged and applauded based on his 2018 book, not on his 2017 writings or videos; we should excuse his early, 2017 work.

Hatsis brings a lot to the table, if only a good, constructive publisher (Park Street Press) can rein-in his negative personal tone, and get him to positively construct a specific theory that states what is the case, in a positively delivered, accessible tone.

/ end of hypothesis

Table of Contents for Part II: Psychedelic Mystery Traditions in Ancient Christianity

This Part of the book focuses on entheogenic Christian history (my term).

Chapter 6: The fire-like cup: Psychedelics, Apocalyptic Mysticism, and the Birth of Heaven

A Godless and Libertine Philosophy

The Curse of Adam’s Seed

Radix Apostatica

Opposite It, the Paradise of Joy

Chapter 7: Disciples of Their Own Minds: Gnosticism and Primitive Christian Psychedelia

Mystery of the Lord’s Supper

Sacred Knowledge

Where the Roots of the Universe Are Found

Mystery of the Light Maiden

Precursor of Antichrist

Chapter 8: Patrons of the Serpent: Psychedelics and the Holy Doctrine

The Sleep of Heavenly Contemplation

Christianizing Pagan Psychedelia

Ecstasy Drinks at the Festival of Lamps

The True Story of the Santa

Ink Inclusion

/ end of Table of Contents for Part II, which focuses on Christianity

Publisher’s description, sorted

Condensed & sorted points from the publisher:

General in Western Civ

long tradition of psychedelic magic and religion in Western civilization

how, when, and why different peoples in the Western world utilized sacred psychedelic plants

the discovery of the power of psychedelics and entheogens can be traced to the very first prehistoric expressions of human creativity, with a continuing lineage of psychedelic mystery traditions from antiquity through the Renaissance to the Victorian era and beyond.

how psychedelic practices have been an integral part of the human experience since Neolithic times.

In Jewish, Christian, & Mystery Religion

[what about Christian mainline tradition history?]

Jewish, Roman, and Gnostic traditions

Christian gnostics

how psychedelics were integrated into pagan and Christian magical practices

mystery religions that adopted psychedelics into their occult rites

the psychedelic wines and spirits that accompanied the Dionysian mysteries

role of entheogens in the Mysteries of Eleusis in Greece

the worship of Isis in Egypt

In Other Western Traditions

full range of magical and spiritual practices

ingestion of substances to achieve altered states.

how psychedelics facilitated divinatory dream states for our ancient Neolithic ancestors and helped them find shamanic portals to the spirit world.

magical mystery traditions of the Thessalian witches

alchemists

divination, magic, alchemy, or god and goddess invocation.

Middle Eastern and medieval magicians

ancient priestesses

wise-women

Victorian magicians

magical use of cannabis and opium from the Crusaders to Aleister Crowley.

/ end of publisher’ description, sorted

Mushroom Art Search Links

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=jesus+mushroom

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=christ+mushroom

https://www.samwoolfe.com/2013/04/the-sacred-mushroom-and-cross-by-john.html – a couple “new” pics, pretty good Comments discussion/debate

https://www.pinterest.com/SimoneQ2/the-mushroom-in-religion/

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/489133209510411085/ – Canterbury, Daliesque mushroom tree on lower left panel of folio 5v/, February 2020, saved by Simone Q. Man hanging from right elbow from a mushroom tree with 1 stem, 12 caps. Left hand on vessel with flowing stream/fountainhead/wellspring.

Comments on Part II: Psychedelic Mystery Traditions, for each subheading

This Part of the book focuses on entheogenic Christian history (my term).

Below are all of the section headings from the Part II Table of Contents, with commentary.

Chapter 6: The fire-like cup: Psychedelics, Apocalyptic Mysticism, and the Birth of Heaven

A Godless and Libertine Philosophy – p139 “Allegro… these researchers argued that the main Christian entheogenic sacrament was the Amanita muscaria mushroom. … the lack of evidence for this claim … The supposed mushrooms that appear in Christian art are easily explained away through a series of sound, tried-and-true historical criteria, which those who still support the theory (in one variety or another) have simply not considered.”

At “not considered”, Hatsis links to psychedelicwitch.com (which now redirects to psychedelichistorican.com), articles “Mushrooms in Mommy Fortuna’s Midnight Carnival” https://psychedelichistorian.com/the-mushroom-in-mommy-fortunas-midnight-carnival/ and “The Secret Christian Radish Cult” https://psychedelichistorian.com/the-christian-radish-cult/ .

“not considered” is false. I read his arguments and debunked them in Egodeath Yahoo Group posts. Hatsis is illiterate at reading mythology art.

Hatsis pulls the Andy Letcher move of trying to find & formulate the weakest, poorest theory, then disprove that bad theory which he formulated and selected, and then make it sound like because his bad theory-formulation isn’t supported, therefore “Amanita isn’t in Christian historical religious practice or traditional Christian art”, which is false.

p140 “There isn’t a shred of evidence to suggest that medieval artists secretly signified entheogens as the fruit by depicting the Amanita muscaria mushroom into art. There does exist, however, evidence for such psychedelic mystery traditions, … in … literature …”

Has Hatsis seen the art findings showing Amanita (and Psilcybe) in Christian art? Entheos journal, Web image searches, etc. There are depictions of Amanita and Psilocybe throughout Christian art. The ‘mushroom’ in religious art means “the loose cognitive state induced by visionary plants”, and the hidden knowledge that is revealed.

‘Visionary plants’ can include cannabis (especially ingested through the stomach, rather than lungs), scopalamine, DMT, salvia, opiates, and mixtures. p143 Hatsis uses the term ‘visionary plants’.

Commentary on book part II section headings, continued

The Curse of Adam’s Seed

Radix Apostatica

Opposite It, the Paradise of Joy

Chapter 7: Disciples of Their Own Minds: Gnosticism and Primitive Christian Psychedelia

Mystery of the Lord’s Supper

Sacred Knowledge

Where the Roots of the Universe Are Found

Mystery of the Light Maiden

Precursor of Antichrist

Chapter 8: Patrons of the Serpent: Psychedelics and the Holy Doctrine

The Sleep of Heavenly Contemplation

Christianizing Pagan Psychedelia

Ecstasy Drinks at the Festival of Lamps

The True Story of the Santa

Ink Inclusion – “Christianity absolutely had psychedelic mystery traditions throughout its history–nearly up to the modern day. … Psychedelia has been part of Christianity since its earliest days.” “the so-called sacred mushroom hypothesis. … The paintings supposedly feature hundreds of mushrooms, but the texts leave not a trace. Why wasn’t the mushroom included [in the texts]? It makes no sense.” (his emph at end) “Our human history is rich with psychedelic history. let’s not desperately try to rivet Amanita muscaria customs onto Christianity where no[sic] evidence for them exists.” Why does Hatsis act like only text, not art, counts as evidence? Is Hatsis equipped to read analogical descriptions, in texts?

Transcendent Knowledge Podcast, episode 21, discusses James Kent and these issues. https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2020/11/07/transcendent-knowledge-podcast-episodes/

Amanita in Christian or Greek art does not mean Amanita; it means the “loose cognitive association binding” state of consciousness, which is induced through various plants.

In religious art, ‘mushroom’ means loose cognition induced by visionary plants. (I use the word ‘plants’ as shorthand to include fungi.)

Article: The Christian Radish Cult

https://psychedelichistorian.com/the-christian-radish-cult/

“1. The overwhelming majority of the supposed mushroom motifs can really be many things. Do some look like mushrooms? Sure! But these are so few and far between”. The article focuses mostly on the easy target, of John Rush’s book’s DVD images.

“2. Even if some of the pictures do represent mushrooms, there is no way of knowing that the artist meant them to be hallucinogenic transportation tools into the spirit world; they could just be mushrooms for eating. Furthermore, mushrooms do not start appearing in European artwork in earnest until the late 15th century; and when they do, they aren’t ambiguous.”

Why would non-psychoactive mushrooms be in a religious mythology painting? It’s in the interest of the genre to take advantage of mystic things, not replace them by non-mystic things.

“3. Too many of Rush’s plates are pictures of folds in clothing – which, so long as you aren’t at a zentai-suit convention, will usually pop up in images that have people wearing clothing. But using this standard, one could find a mushroom in almost every picture ever painted”

“What Rush has done is embroidered his modern western ideas about mushrooms onto ancient cultures …

“Maybe Rush is correct; a Christian Mushroom Cult existed secretly for centuries, and while the members feared persecution, torture, and death they still found time to include mushrooms in their paintings. Unfortunately, anonymous tips, curls in clothing and hair, and distrusting your own eyes (by seeing a mushroom where none is evident30) simply do not count as the kind of hardcore evidence needed to prove a Christian Mushroom Cult existed.”

Notice Hatsis’ focus on ‘secrecy’, as if “secrecy” and Allegro’s “Secret Mushroom Cult” (Hatsis’ capitalization) is identical with the mushroom theory of Christianity.

Hatsis is just nothing more than yet another member of a clan: the Wasson/Letcher/Hatsis gang, pulling their standard moves, of picking and focusing on the weakest theory they can find (“Secret Mushroom Cult”), as if it is definitive and the only theory-version, then dismissing that narrowest theory, and then acting like they disproved the broad proposal of mushrooms in Christian history.

Hatsis didn’t even have the integrity to include his arguments within the book, but instead, just included a straight-out-of-Wasson, smug authoritarian insult. “We have a tried-and-true scholarly method, and other people are just ignorant of our proven, sound method.”

/ Radish article

Article: The Mushroom in Mommy Fortuna’s Midnight Carnival

This is one of the two articles that Hatsis points in his book, where he asserts that he has “sound, tried-and-true historical criteria” that prove that no Christian art has mushrooms — criteria which no mushroom theorist has ever considered, which if they would only take a moment to consider, they would readily grant the devastating finality of Hatsis’ proof that there are no psychoactive mushrooms in Christian art.

I commented on this article as well, in the Egodeath Yahoo Group, around 2017.

“The supposed mushrooms that appear in Christian art are easily explained away through sound, tried-and-true historical criteria, which those who still support the theory (in one variety or another) have simply not considered.” — Hatsis’ book, p. 139

Excerpts from Hatsis’ Carnival article:

“More Unsubstantiated Claims of the Holy Mushroom Theory”

“to preempt one of the more common (but ultimately shallow) arguments (“you only addressed one picture!”) against my article Christian Mushroom Theorists vs. Critical Historical Inquiry[URL not found; article title not found now], I offer further evidence that these mushroom advocates are a little too quick to label something a “mushroom”, or mask lax methodology behind vague sophistry like saying that the mushrooms are hidden1. If my other articles haven’t demonstrated how flippant many of Irvin, Rush and the rest’s conclusions are, maybe the following will.”

“Irvin’s The Holy Mushroom offers this image of St. Martin as further proof that artists “secretly” depicted mushrooms in their works. This window from Chartres Cathedral, France…”

“Assuming that St. Martin can’t both raise the child from the dead and point to an “amanita” tree, what is he doing? … St. Martin is not “pointing” at anything. His hand is in a standard Christian blessing position”

Notice how Irvin and Hatsis are debating always in terms of ‘Amanita’. I’d just say “mushroom”, that happens to be red. Amanita is needlessly specific.

“the supposed “amanita” that Martin is “pointing upward at” is more likely just a tree; the legend specifically takes place in a field. While mushrooms can grow in a field, that is not enough to show that the tree in the window is supposed to be an amanita.”

“Irvin includes another image that supposedly captures St. Martin alongside an amanita muscaria in Panel 13″

“On the lower right of the panel we see the same amanita that appears in Panel 13. Only Martin isn’t painted into either panel 13 or 15!”

“Thus, Irvin’s claim that Martin is “glaring at an Amanita muscaria complete with spots” in Panel 13 is wholly erroneous.

“there are no mushrooms for Martin to mingle with in this stained-glass piece that clearly takes place indoors. Therefore, while the field tree of Panel 18 might have secretly represented the 4th century bishop as a mushroom, Martin’s absence from Panels 13 and 15, which both depict the same kind of amanita mushroom-tree found in Panel 18, should be enough to reject the premise that medieval artists associated St. Martin with divine mushrooms.

“There is, of course, the possibility that a lack of indoor fungi present in Panel 14 will cause Irvin to default the “mushroom motif” to the halo (or aureola) around Martin’s head. After all, it is red and “cap-like”. While anyone should be able to see that such a tactic would only typify moving the goalpost after the punt8, I feel that I should comment on it; one Mushroom Cult researcher has already made a similar argument9.

“Figure 6 is an enlarged cropping of the halo (aureola) around Martin’s head. Perhaps the halo is there to represent a mushroom; but there also might be a more reasonable answer.”

The Amanita-fixation fallacy:

“The panels that depict Martin dying are curious in their detail; these panels show him with a red, blue, or green, halo. Panel 32 shows him with both: his corpse wears a blue halo; his soul rejects Satan while wearing the red halo.

“Therefore, if the halo is supposed to be an amanita muscaria, Christian Mushroom Cult theorists also have to explain all these other facts about them. Does amanita have properties that make it change from red to blue to green and back to red again? What Christian legend will the Mushroom Cult theorists use to make this (his)story fit correctly into their ideas?

“One of the details Mushroom Cult theorists like Irvin use to prove their case is that these improbable amanita trees come “complete with spots”15. I admit that both red trees in Panels 13 and 15 come with etchings that could be called spots. But then how will Mushroom Cult theorists contend with these trees from bestiaries — red capped, complete with spots?

“Is this asp (Figure 8) from the Aberdeen Bestiary (12th century) clinging to a “mushroom-tree”? After all, the top is red with passable “white spots”. Where do asps fit into the Christian Mushroom Cult theory?”

Where do serpents fit into the “mushrooms in Christian mythology”, the Egodeath theory answers that question. The so-called “Christian Mushroom Cult theory” (Hatsis’ term, I believe), is a separate matter.

Here, Hatsis shows good bestiary images, showing mushrooms, demonstrating that there aren’t mushrooms in Christian mythology art. See the article for many good images of mushrooms, piling up the evidence for the lack of mushrooms.

“In The Holy Mushroom, Irvin credits these mushroom trees as “the provider of Jacob’s vision — climbing the ladder to heaven.”

“But this resemblance to that secular genus of text is not the Mushroom Cult theory’s biggest problem; the biggest problem is what to do with all the other illuminations that portray mushroom trees (by the theorists’ standards, anyway) when they appear in scenes of violence. We see, also from the Munich Psalter, the same mushroom trees that supposedly gave Jacob his vision.”

“Truly amazing is that this picture testifies to a 13th century popular familiarity with ideas long-since stamped out of Christendom! How do the magic mushroom-trees, evident in this folio, work into the parable of Lamech accidentally slaying Cain? If these trees caused Jacob’s visions, they must, by any rule of fair-minded and objective scholarship, also account for Lamech’s deadly mishap.”

What a brittle demand Hatsis puts forward. Not only must mushrooms be shown, they must be shown with certain values, or they aren’t mushrooms.

Hatsis has a brittle mental separation between “spiritual vs. nonspiritual art”. He continues to fixate on ‘red’. And like a non-poet, he commits the single-meaning fallacy, arguing that if an image means a tree, it cannot also mean a mushroom:

“Trees of this kind appear in Latin bestiaries and numerous other nonspiritual works despite Rush’s claim that “mushroom shapes are rare in secular art”21; and when they do, they always represent trees. The leaves tend to appear in a variety of colors: purple, green, blue, and of course, red. Christian Mushroom Cult theorists like Irvin need to explain how they know these pictures are mushrooms when all available evidence says otherwise. Gold Munich Psalter shows a style of tree that looks very “psychedelic” indeed, but it always ends up the same: when you put the “mushroom tree” in historical context, it never ends up being a mushroom.

Never ends up? Hatsis commits the single-meaning fallacy.