Page by Cybermonk December 11, 2020. Original page title, per url:

Brinckmann, Mushroom Trees, & Asymmetrical Branching

Contents:

- Citation of Brinckmann’s Book

- The Incredible Shrinking “Art Historians Have Already Discussed Mushroom-Trees” Claim by Panofsky

- Info About Brinckmann

- Plates from Brinckmann’s Book

Citation of Brinckmann’s Book

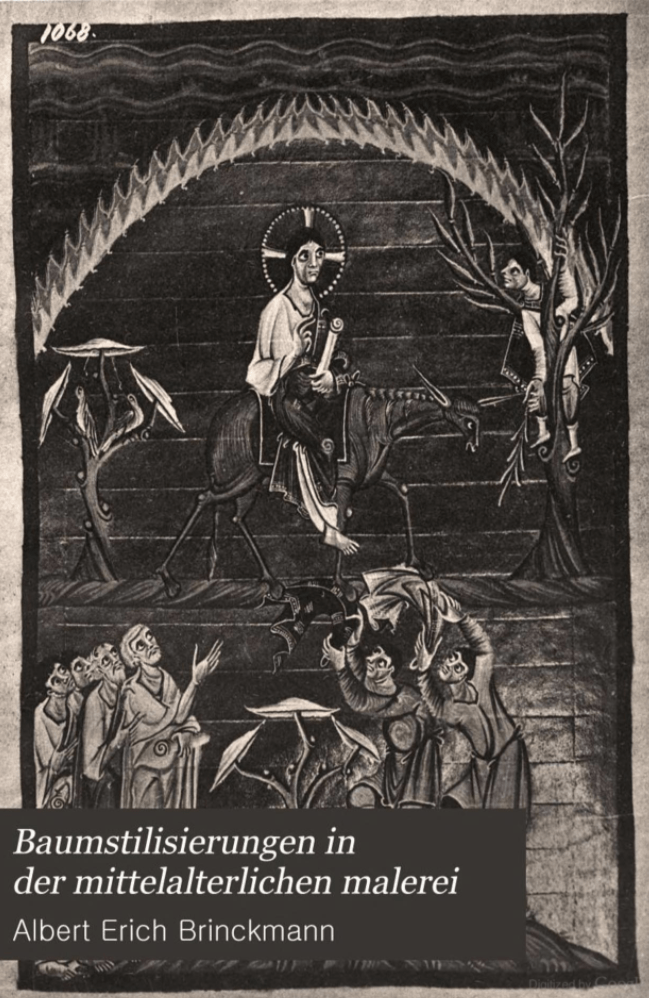

Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen Malerei

(Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings)

Albert Erich Brinckmann, 1906

86 pages

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/mode/2up

The 9 plates, at the end, are copied to the present page.

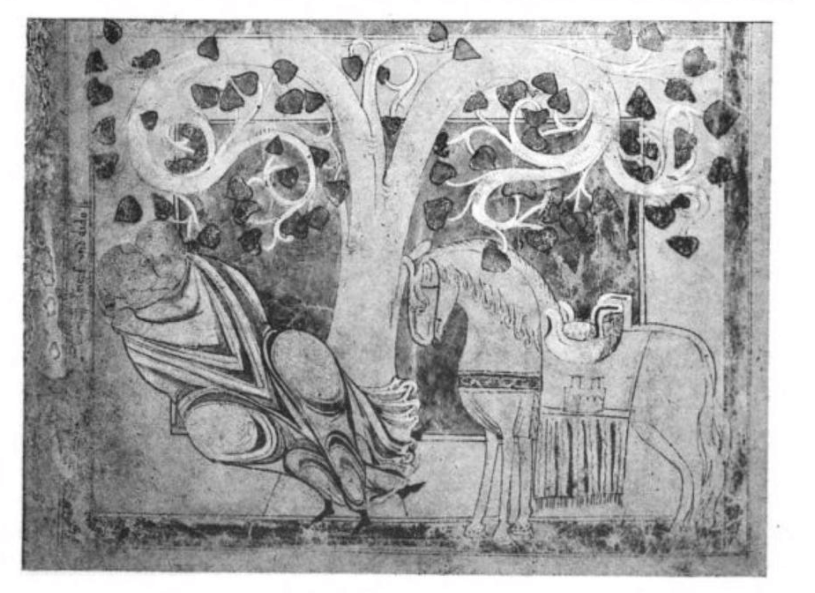

6 plates with some 10 plant schematizations each, and 3 plates with 4-5 works of art:

o Jesus riding a donkey (same as cover)

o 2-in-1: Vegetation + small rearing horse

o a) Eden tree, b) reclining/tree/horse

http://amzn.com/3957383749 – reprint in U.S.,

Publisher : Vero Verlag GmbH & Co.KG (February 15, 2014)

https://www.amazon.de/-/en/Albert-Erich-Brinckmann/dp/0243487665/ – reprint in Germany, publisher: Publisher : Forgotten Books (30 Nov. 2018)

Alt titles of this page:

Brinckmann & Asymmetrical Branching/ Non-branching Trees in Christian Art

The Name “Brinckmann” Appears Three Times in Panofsky’s Two Letters to Wasson, Including His Full Name and Book Title in Wasson’s Own Hand

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2022/03/09/idea-development-page-13/#Brinckmann-3-times

The Incredible Shrinking “Art Historians Have Already Discussed Mushroom-Trees” Claim by Panofsky

Erwin Panofsky wrote to Wasson in 1952:

… the plant in this fresco has nothing whatever to do with mushrooms … and the similarity with Amanita muscaria is purely fortuitous. The Plaincourault fresco is only one example – and, since the style is provincial, a particularly deceptive one – of a conventionalized tree type, prevalent in Romanesque and early Gothic art, which art historians actually refer to as a ‘mushroom tree’ or in German, Pilzbaum. It comes about by the gradual schematization of the impressionistically rendered Italian pine tree in Roman and early Christian painting, and there are hundreds of instances exemplifying this development – unknown of course to mycologists. … What the mycologists have overlooked is that the medieval artists hardly ever worked from nature but from classical prototypes which in the course of repeated copying became quite unrecognizable. – Erwin Panofsky in a 1952 letter to Wasson excerpted in Soma, pp. 179-180

[Beware of ellipses! Pope Wasson here omitted Panofsky’s citation of Brinckmann’s book.]

Meyer Schapiro, another art historian, asserted the same argument in communications with Wasson.

I couldn’t find an English version of Brinckmann’s book. I didn’t hear back from German entheogen scholar Christian Ratsch.

I just found a significant word-mistranslation. Brinckmann actually wrote ‘grapevine’ where this translator wrote ‘vine’.

The translation is of Chapter 1 of 5, and of the final quarter of Chapter 5.

Those chapters don’t seem to have the word ‘mushroom’ — SO PANOFSKY’S CLAIM THAT “THE ART HISTORIANS HAVE DISCUSSED mushroom trees” is shrinking and shrinking, down to what, 3.75 short chapters at most?

3.75/5 of 86 pages = 0.75 * 86 = 65 pages of “coverage” of the topic, in one book by one art historian, in 1906?

THAT’S ALL YOU GOT??

No wonder Pope Wasson censored Brinckmann’s name & book, it is so puny and underwhelming coverage of the matter, the topic of mushroom trees!

to try to “refute” the mycologyists (NOT Allegro!; long before him):

- Rolfe’s mycology book — 1925.

- Ramsbottom’s mycology book — 1949.

- Panofsky’s letter — 1952.

- Ramsbottom’s mycology book — 1953.

- Brightman’s mycology book — 1966.

- Allegro’s Philogy/fertility book (non-mycology, non-entheogen-scholarship) — 1970.

Allegro’s book “The Sacred Mushroom and The Cross: A study of the nature and origins of Christianity within the fertility cults of the ancient Near East” was 1970 (2009 Irvin reissue).

Wasson & Panofsky first claimed that the mycologists (NOT Allegro!!) were wrong about this one image, Plaincourault, in 1952 — 18 years (2 decades) before Allegro’s book!

http://www.egodeath.com/WassonEdenTree.htm#_Toc135889188

Info About Brinckmann

Dictionary of Art Historians: Brinckmann, Albert

https://arthistorians.info/brinckmanna

German Wikipedia entry about Brinckmann: Albert Erich Brinckmann

https://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Erich_Brinckmann

English translation:

https://www.translatetheweb.com/?ref=TVert&from=&to=en&a=https%3A%2F%2Fde.m.wikipedia.org%2Fwiki%2FAlbert_Erich_Brinckmann

To confirm a theme that the Egodeath theory’s Mytheme theory predicts (branching on left, non-branching on right),

To confirm the theme of {branching on left, non-branching on right}, I’d ideally need:

- The original art that Brinkmann used to draw his shape-diagrams.

- An English translation of Brinckmann’s book.

- Brinkmann’s captions in English, for the numbered shape-illustrations in each plate.

- It would be better to work with a set of data that was collected by someone who is aware of the “branching vs. non-branching” theme and the “left = false = branching, right = true = non-branching” theme.

I can’t trust the left/right orientation in Brinckmann’s plates.

There are reversed photographs of a Tauroctony, so that Mithras is forgetting, rather than remembering.

Plates from Brinckmann’s Book

Table of Contents for Plates

(The numbers in parentheses indicate the text pages.)

Translated pages:

Chapter I: 1-7

Final quarter of Chapter V: 48-52

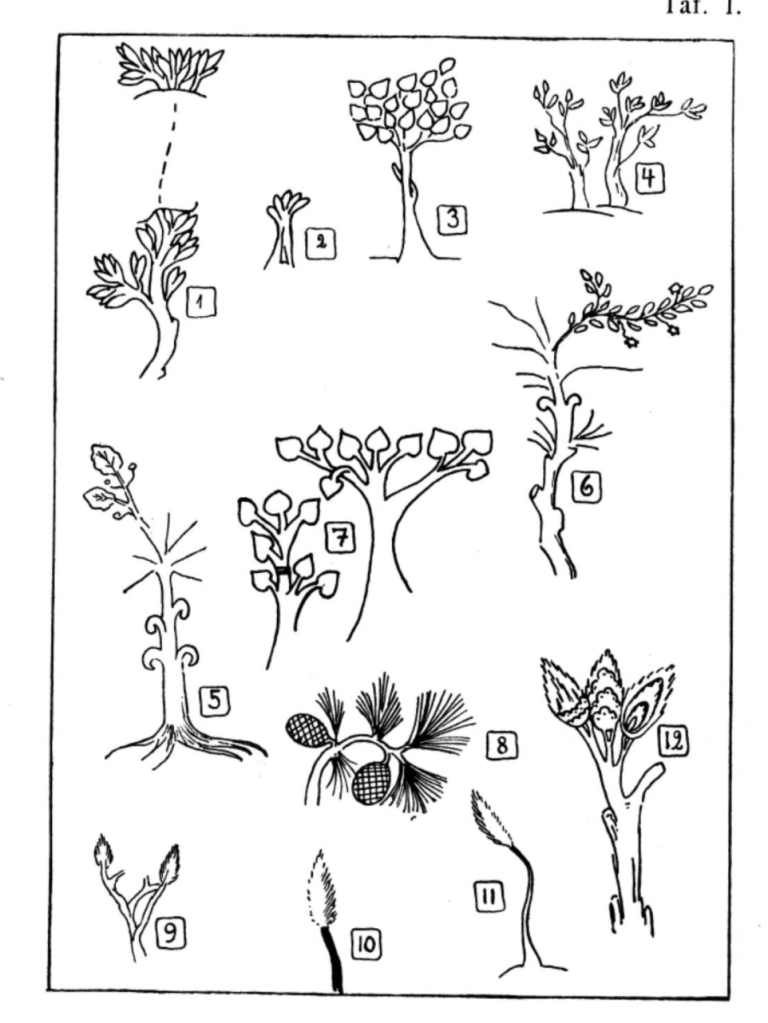

Diagrams of Forms

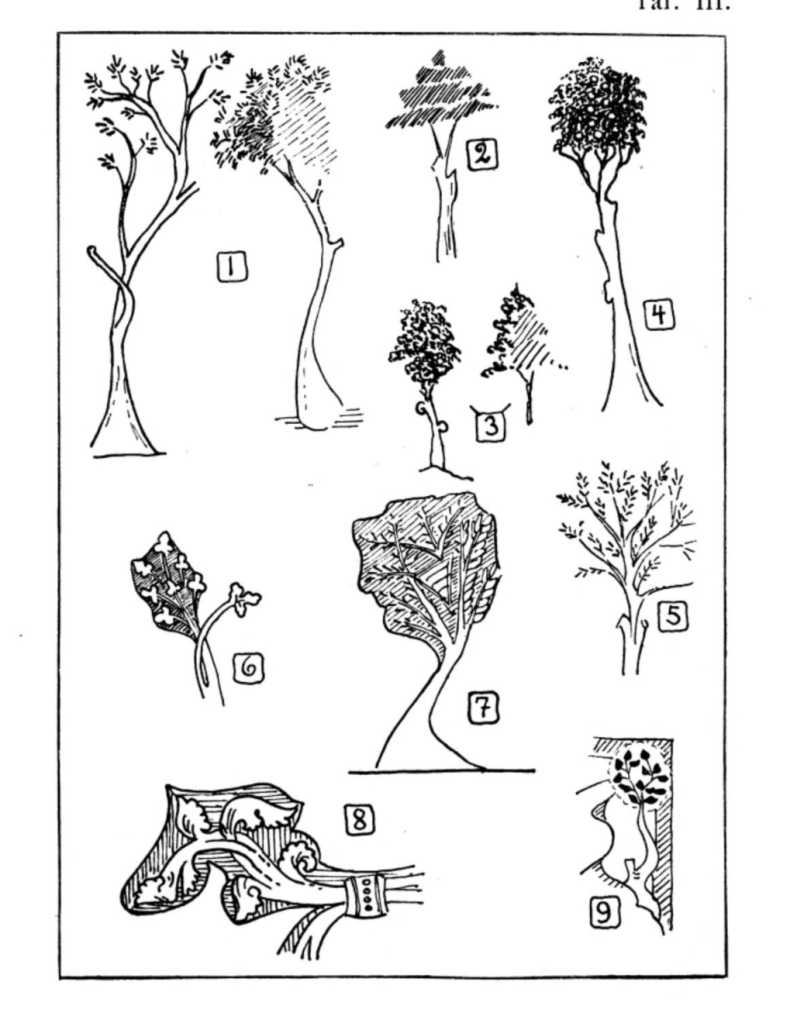

Plate 1

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n63/mode/2up

Shapes in Plate 1, regarding branching morphology:

- Right side debranched in 2 spots.

- x

- Right branch cut off, wraps left.

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

- Branching yet all the branching branches are cut off, on the left.

- x

- x

- Left branches, right cut off (like the Pink Key Tree in Canterbury “mushroom tree/ hanging/ sword” image with the trained, self-threatening Psalter reader).

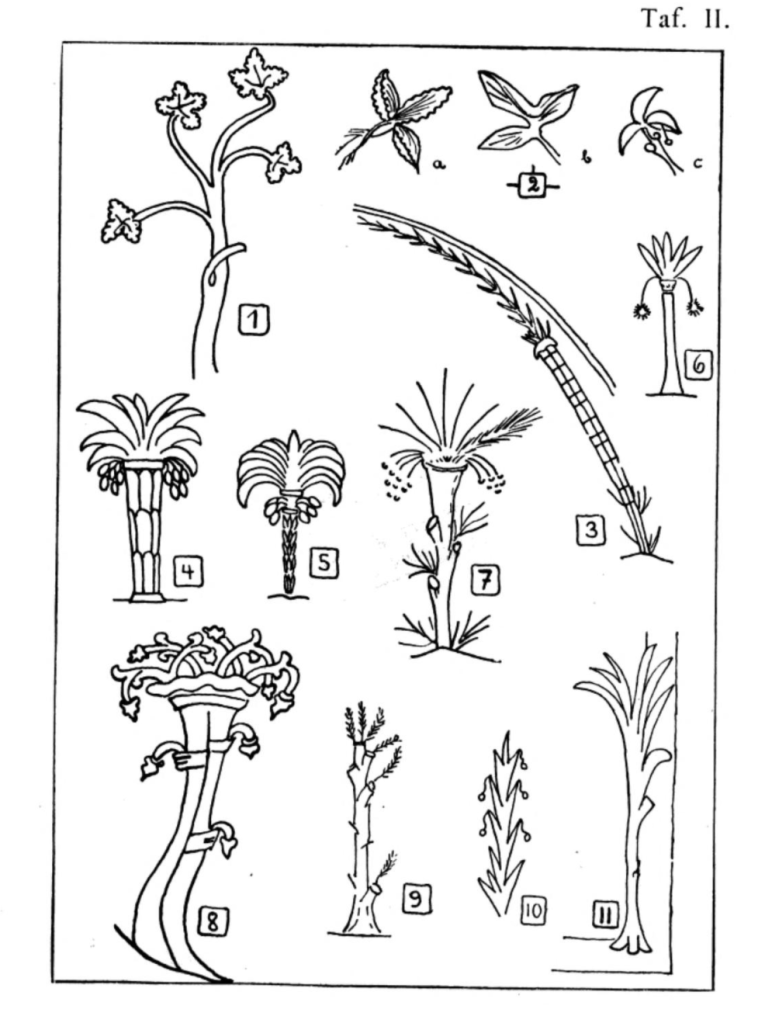

Plate 2

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n65/mode/2up

Shapes in Plate 2, regarding branching morphology:

- Similar to the Pink Key Tree in Canterbury “mushroom tree/ hanging/ sword” image with the trained, self-threatening Psalter reader. Left branch is cut off, wraps to become right.

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

- Debranched 2x on left, 1x on right.

- x

- Debranched 1x on left, 3x on right.

- x

- Branching on left, 2 cuttoff branches on right.

Plate 3

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n67/mode/2up

Shapes in Plate 3, regarding branching morphology:

- Left diagram: Left branching (part of it is debranched on right), right cut off and wraps left.

Right diagram: Branching on left, 2 debranched stubs on right. - Branching on left, debranched on right. Need to see original.

- x

- Unclear digram. 2 cut branches on left, 1 on right possibly.

- x

- Right has branching but veers to become left; left is non-branching but veers to the right.

- x

- x

- Cut left, branching right.

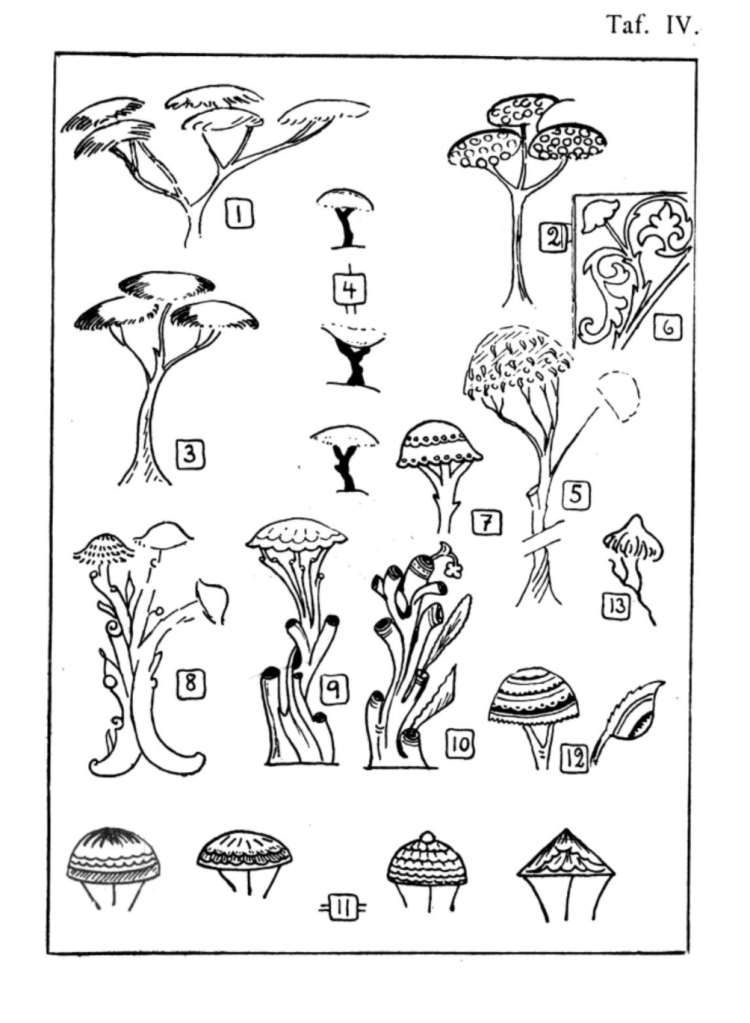

Plate 4

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n69/mode/2up

Shapes in Plate 4, regarding branching morphology:

- x

- x

- x

- x

- Cut on left. Hazy on far right.

- x

- 1 cut on left, 1 on right.

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

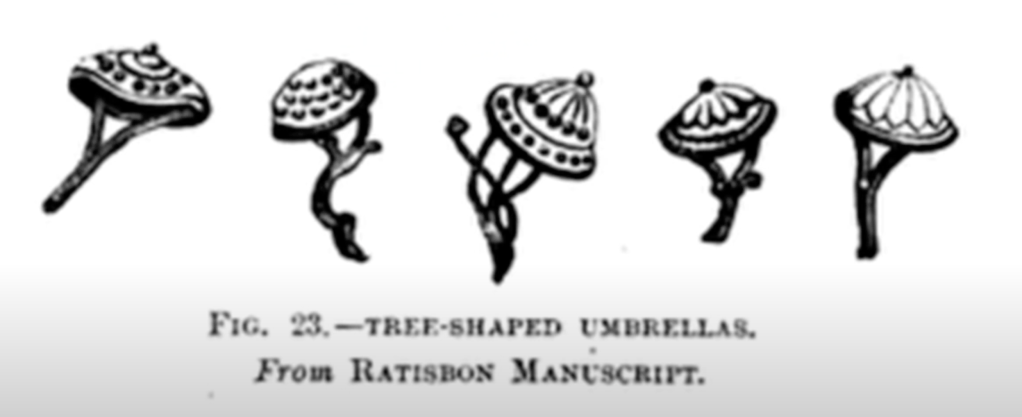

Mushroom Trees Debunked

YouTube channel: Psychedelic Historian

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrfeNp1FSUY

At about 55% through, he shows this illustration:

Cover of cista mystica snake basket is flat or round decorated:

Plate 5

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n71/mode/2up

Shapes in Plate 5, regarding branching morphology:

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

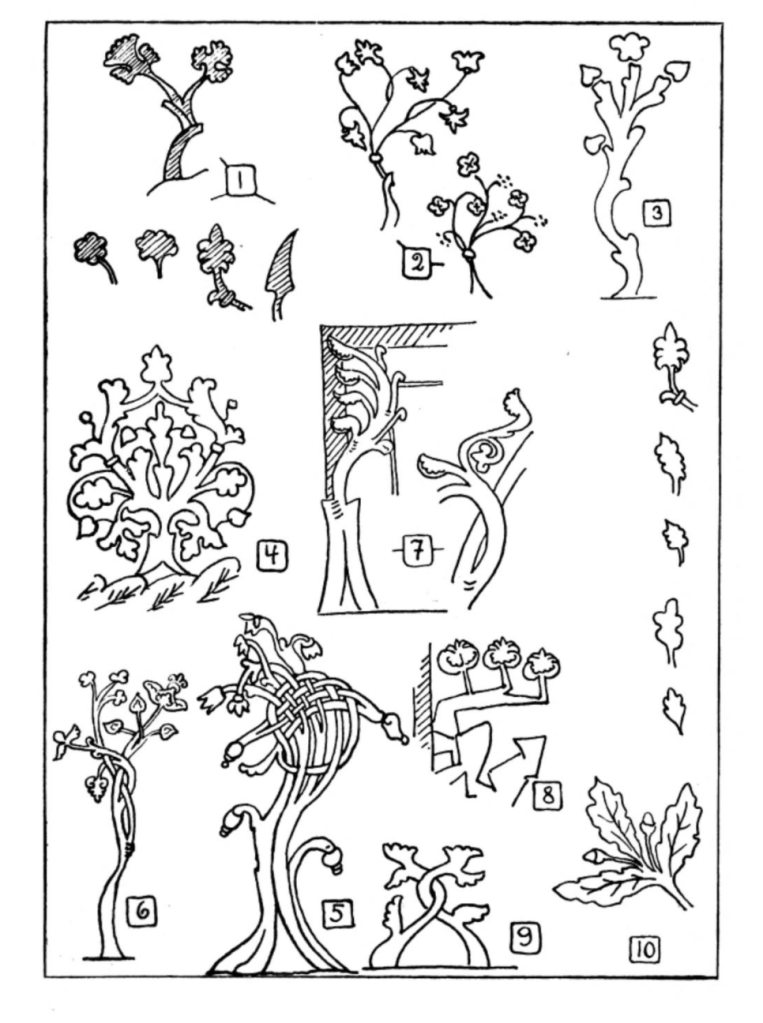

Plate 6

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n73/mode/2up

Shapes in Plate 1, regarding branching morphology:

- x

- Right becomes left, and branches. Left becomes right, and apparently is cut off (need original).

- x

- x

- x

- Common theme of one worldline branching into two: the control-thought receiver’s worldline + the control-thought inserter’s worldline. Within the cap/canopy, there are similarly, a pair of laurel-shrub non-branching branches, like could form a wreath-crown.

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

- x

Art Images

Plate 7

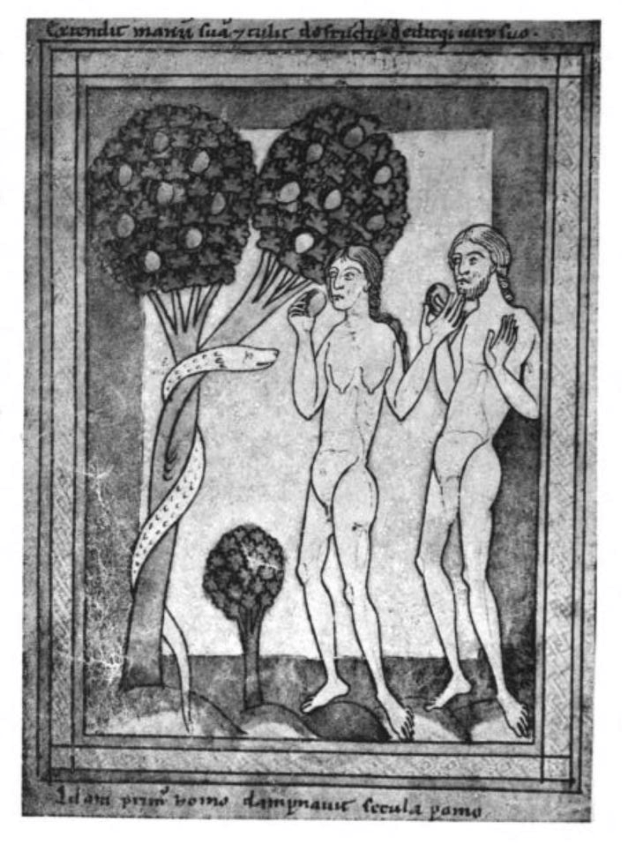

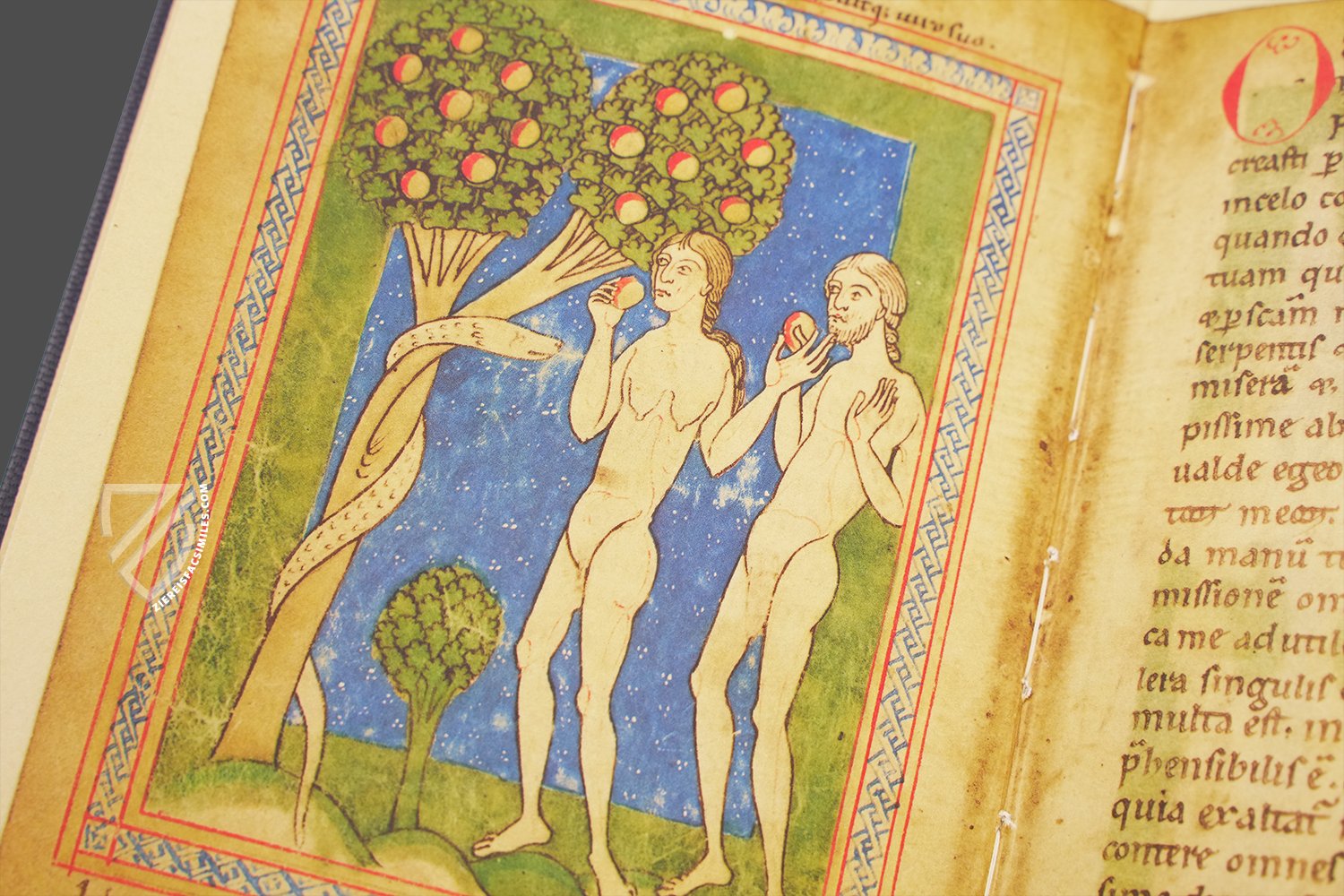

“wasserzeichen-projekte crop.jpeg” 411 KB [11:13 a.m. February 20, 2023]

Crop by Cybermonk. url https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/0009/bsb00096593/images/index.html?fip=193.174.98.30&seite=94

Hi-res color upstream source found and added by Cybermonk February 20, 2023.

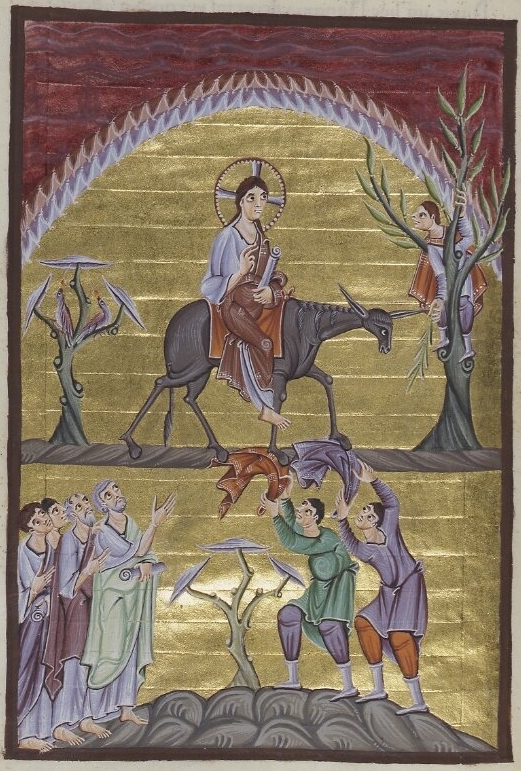

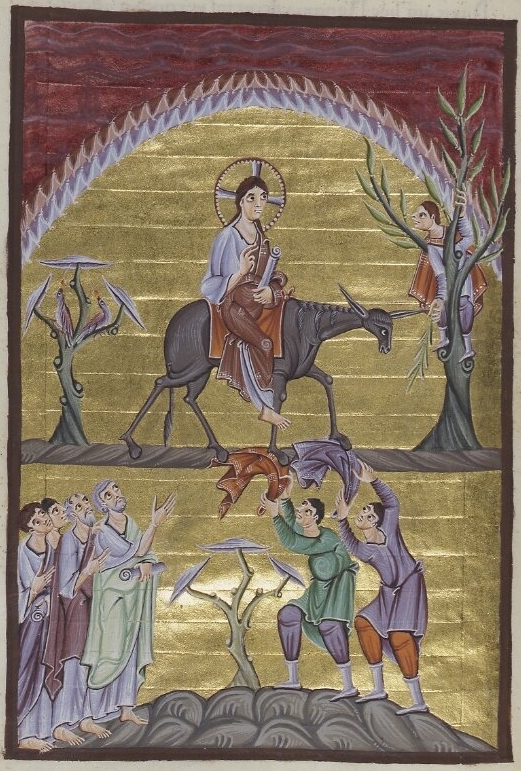

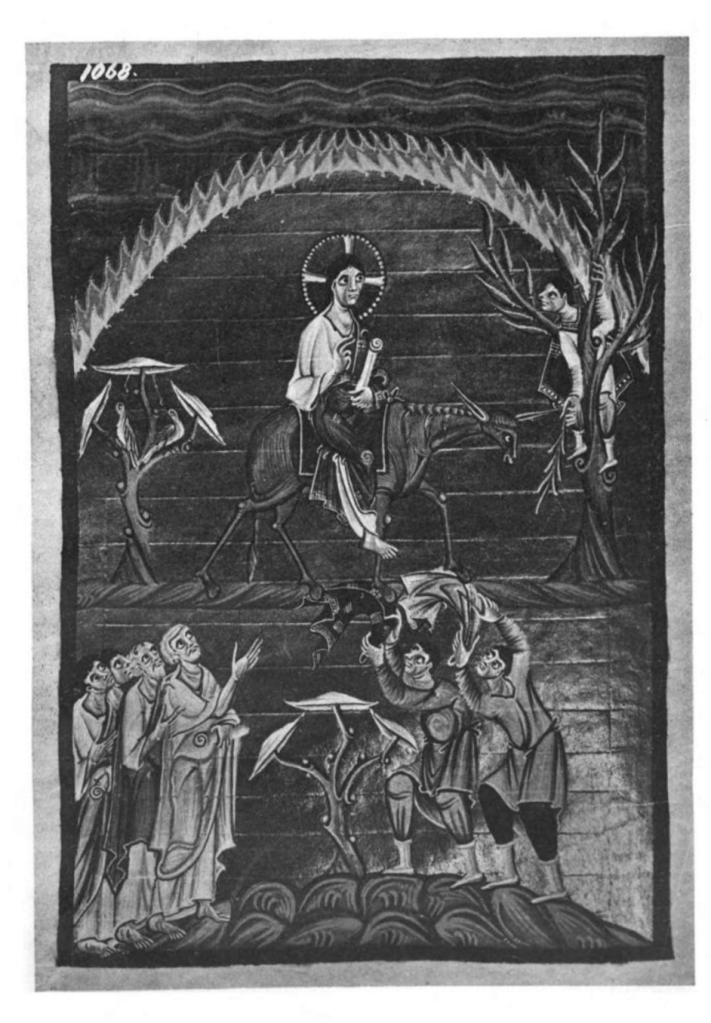

Entry into Jerusalem. Das sogenannte Evangeliarium Kaiser Ottos III (The so-called Evangeliarium of Emperor Otto), Latin Codex 4453, Munich, around 1000 CE. https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n75/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n75/mode/2up

Plate 8

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n77/mode/2up

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carmina_Burana

Samorini’s commentary: https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/mushroom-trees-in-christian-art-samorini/#Figure-12

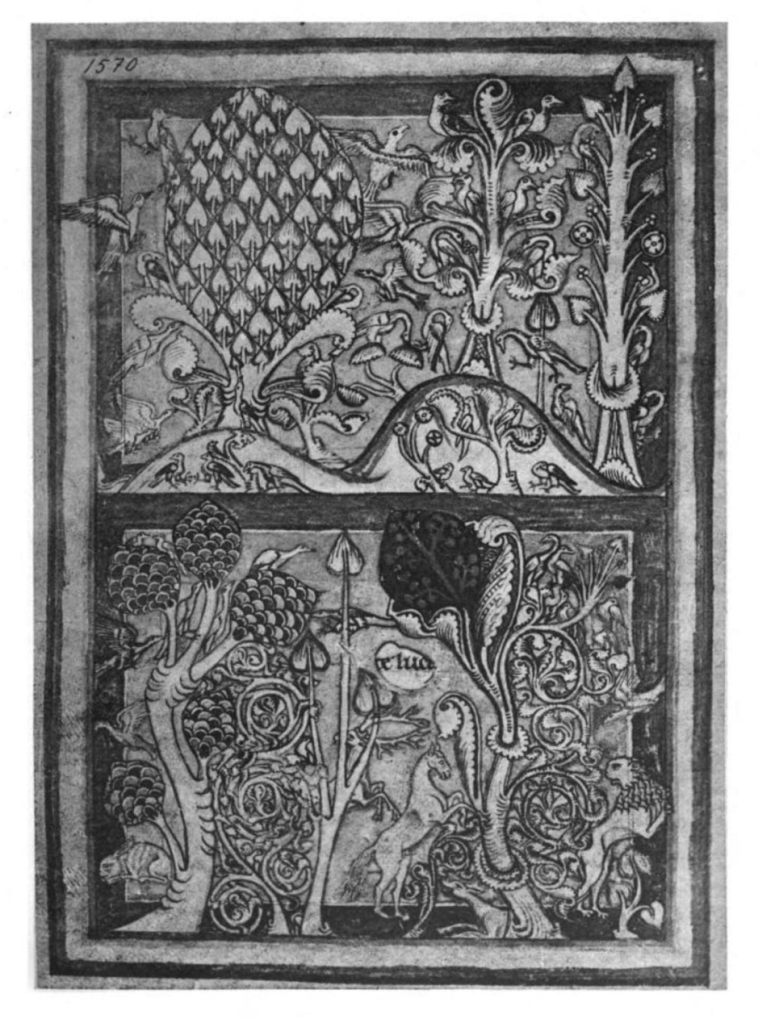

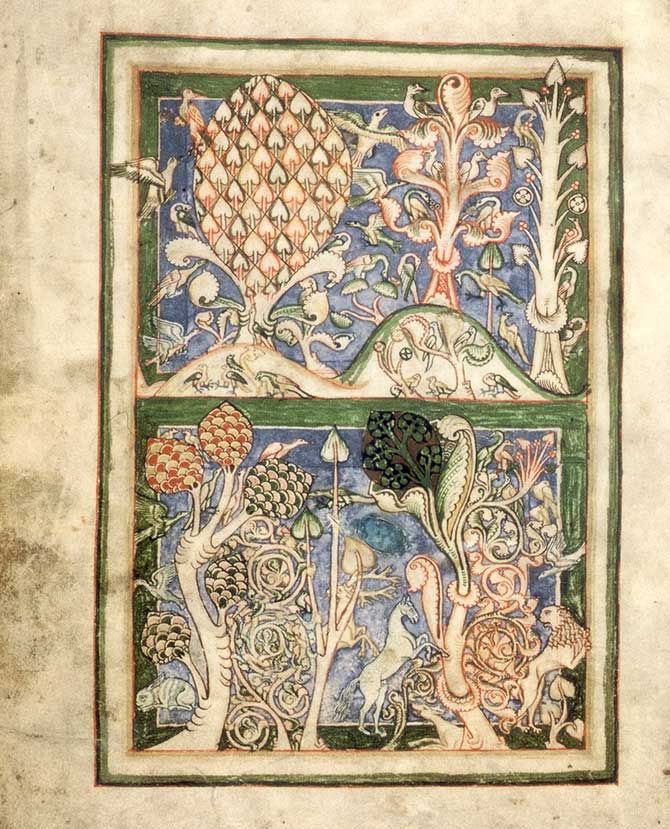

Plate 9

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n79/mode/2up

https://www.facsimiles.com/facsimiles/book-of-hours-of-hildegard-von-bingen

I analyzed the above image at:

Article:

Defining “Compelling Evidence” & “Criteria of Proof” for Mushrooms in Christian Art

Subsection:

Brinckmann’s Book that Proves with Finality that Mushroom Trees Are Trees, Not Mushrooms

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2020/11/13/compelling-evidence-criteria-of-proof-for-greek-bible-mushrooms/#bbtpwf

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n79/mode/2up

Translation of Chapter I and Final Quarter of Chapter V

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n3/mode/2up

STUDIES ABOUT GERMAN HISTORY OF ART

ISSUE 69

TREE STYLIZATIONS

IN

MEDIEVAL PAINTING

BY

A. E. BRINCKMANN

DR. PHIL.

WITH 9 TABLES

Painting is the mere visibility of the will.

Schopenhauer.

STRASSBURG

J.H. ED. HEITZ (HEITZ & MÜNDEL)

1906

Table of Contents

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n5/mode/2up

I. Early Christian art in Italy……page 1

II. Byzantine painting…….page 8

III. Carolingian art………page 15

IV. Carolingian tradition and Byzantine influence…..page 24

V. New forms……page 33

Index of Tables………page 53

Pages in this translation to English:

Chapter I: Early Christian Art in Italy – Pages 1-7

Chapter V: New Forms – Pages 48-52 (5 pages), not 33-47 (15 pages)

Chapter I: Early Christian Art in Italy

Page 1

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n7/mode/2up

I.

EARLY CHRISTIAN ART IN ITALY.

The Christian artistic impulse initially contents itself with poor borrowings from the simultaneous rich – even though partially craftily and schematically producing – Roman art. The producing powers are too steadfast in their time to create a change of the presentation circle, let alone the presentation forms without long transitions; only the new content that is given to it modifies the old form.1 There are no reasons for the non-reproduction of nature or even for a conscious renunciation of nature. In the catacombs of San Gennaro dei Poveri,2 as in the Coemeterium of the holy Domitilla, there are landscape displays that show – despite all barrenness – that a Christian oratory can take the same ornaments as a Roman house, and still the mosaics of S. Constanza (329) give pagan-antique decoration.

In Roman art, the power of objective naturalistic presentation reached its peak in the first century AD. When developing further, the aspiration to give only the appearance and to not anymore display the body, which encompasses the sense of touch, becomes apparent, floating beyond individual forms in an impressionist manner. It is left to the

1 Julius Lange, The Human Gestalt in the History of Art. Transl. Straßb. 1903. Page 442: “Christianity gives the subjectivity instructions for an infinite content and infinite dimensions and directly and indirectly accounts for a completely new concept of mankind.”

2 Vict. Schutze, The Catacombs of S. Gennaro dei Poveri, Jena 1877, by the same. The Catacombs, Leipzig 1882.

BRINCKMANN 1

Page 2

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n9/mode/2up

substituting experiences of the observer to make the last connection of optical impressions of the form him/herself.1 When it comes to painted tree images, this illusionism gives the picturesque mass in which neither leaves nor branches are silhouetted, or he sets lighter and darker spots with a fine brush in a soft way in trees with tender leaves, so that the crown is an aromatically shimmering product of strokes and spots. At the same time, in the Hellenistic relief plastic, a manner of presentation emerged, which shows the individual scenery elements not physically anymore, not in terms of the body, but area-wise, or in other words, compressed flat. The individual plans of the scenery are not ordered/organized one after another but one above another; the ideal area of the scenery that leads right into the relief thus does not build – with the real, vertical relief area –a right angle but a more or less acute or pointed angle, i.e. the presented area is folded upward against the spectator.2 As far as the trees are concerned, the branches that build the treetop are taken apart and are compressed onto an ideal vertical level, yet the individual leaves are created supernaturally/extraordinarily big and in a precisely detailed way. Both presentation manners cross in the early Christian and Byzantine art.

The sculptors of the earlier Christian sarcophaguses3 take over the tree stylizations of Roman art, even though their variety of modes is already limited. In the beginning, the laurel tree is seen a lot; already strict and hard in the contours but still characteristic in trunk and leaf on a sarcophagus in the Louvre (I, 1),4 [Plate 1, diagram 1] stiffer and more reduced to a sarcophagus of the Lateran (I, 2).1 [Plate 1, diagram 2]

[I did lots of botanical laurel shrub research and postings ~2012, at the Egodeath Yahoo Group, re: mytheme {non-branching}; the laurel shrub is primarily nonbranching, like ivy. -mh]

1 Wickhoff, Viener Genesis, Vienna 1895, page 65.

2 compare Schreiber, The Hellenistic Relief Images, Leizpig 1894. The tendency to depict a body as an area/surface is clearly apparent in the representation of a house that is seen laterally. The narrow gable wall is not used in order to make the building appear cubic by means of introducing it into the space of the image, but it is folded in the vertical area of the long side so that the rectangular layout becomes a line.

3 These offer the best examples and have to replace the failing painting. The later plastic, however, was not able to serve as an example due to insufficient classification and lack of publications.

4 Abgeb. Garucci, Storia della arte Cristiana (History of Christian Art). Prato 1879-81. Volume V, page 295.

Page 3

The trunk is short and stocky and the branches and twigs are not gnarly anymore, the long-ish and smooth leaves grow out of it in an area-like manner and lay down next to one another across the surface/area. The oleaster (that is considered sacred) then replaces the bay tree almost entirely later-on. In the symbolic representation of the harvest, it is brought together with antique geniuses and builds an appropriate counterpart to the vintage.2 Besides the palm tree, the oleaster is the special Christian tree in which the holy pigeon [probably the gentle harmless Holy Spirit dove, as opposed to the violent eagle of Zeus -mh] nests and from which twigs are broken off [important {nonbranching} mytheme -mh] for the entry of Christ.3 The trunk resembles the trunk of the bay tree, the leaves are longer, they never sit together in a cloggy/clotty way and spread more freely across the surface/area/ the berries have special stems or two leaves as a chalice. The oak tree is also, especially in meadow/pasture pictures, used manifold, while other kinds of trees are more seldom – the representation of the palm tree is dealt with further below.

From the vast amount of Roman motifs, only the most common ones, i.e. the crafty shapes are taken over: a limitation for the benefit of lesser types. These types all require neglect of nature and come into existence by means of numeric reduction and formal simplification of the mother forms. The tree has only few leaves, whose detailing is raw. The stem, whose leaves often grow out of it without a special stem leaf, is short and stocky and rather a matter, such as an organic plant. The neglect of a living organism allows that vine [important nonbranching mytheme. vine = Weinstock, leaves = Blätter -mh] leaves grow out of an oak tree trunk, i.e. that two forms that were taken over without looking at it in a correcting way are connected to nature. The tree does not have a scenic intrinsic value anymore, it withers as a mere accessory element and loses its proportion toward its surroundings. In this context, the landscape, whose representation the Hellenistic Art loved, disappears and finally also their last rudiments, the trees –

1 Garucci, ibid., page 298.

2 Garucci. Page 381. 322 and 4.

3 Garucci, page 381.

Page 4

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n11/mode/2up

trunkless bushes hardly appear anymore – receive a new assessment.

[The goal in Greek & Christian tree depictions is to contrast branching vs. non-branching; so

1) the non-branching trunk is always depicted, along with

2) branching at top (underside of canopy/cap), and

3a) often non-branching cut-off limbs.

3b) This Brinckmann translation provides a valuable Egodeath Mytheme theory-corroborating clue/point: ivy leaves: ivy’s primarily non-branching shape depicts the important & central, {non-branching} theme.

The goal in mushroom-tree art is to depict the contrast between possibilism (possibility-branching) vs. eternalism (pre-existence of the block universe with worldlines).

from {king steering in tree} (possibilism) through {mixed-wine at banquet} (Psilocybe) to {snake-puppet frozen in rock} (eternalism)

from {king steering in tree} through {mixed wine at banquet} to {snake-puppet frozen in rock}

{king steering in tree} -> {wine} -> {snake frozen in rock}

-mh]

The requirements for artistic creation change, a new principle of representation breaks through. A value shift from descriptive to associative elements, a regression in seeing and representing takes place, which leads to those representation forms of all early art periods that are defined as symbols and whose insinuating shape suffices to trigger/cause the associative process.1

A deeper and deeper living-into-oneself and thinking-into-oneself into the Christian scriptures prepares the new representation principle. These have, as an effusion of the abstract Semitic mind, only a little nature assumption or outlook, descriptions of landscapes out of an intense nature sensation are looked for in vain. The individual forms of nature remain unseen, it does not go being the dry-typical words “vine” [‘Weinstock‘; important non-branching mytheme -mh] or “palm tree”. The spiritual life in the transcendental world makes the eye unreceptive for the forms of the surrounding and has a “de-arting” effect (an effect that takes the art perspective away).2 For example, the limitedness and stiffness of the circle of imagination of formations of nature becomes comprehensible, it is explicable that few forms that are manageable in the associative imaginations, are constantly repeated, yet seem tense due to their constant monotony and thus carry in themselves the reason for their decay. The crafty, not naturalistic production is necessarily followed by the stiff schematizing of the form, the tendency toward the abstract-specified (orthodox) under the loss of the living organism. The human being who gets deeper and deeper into his religion and its dogmas then neglects the senses that connect him to the exterior world. [it is more important to depict {branching vs. non-branching}, as well as {mushroom}, than literal botanical representation -mh] The Christian art, in its striving

1 See the Greek Xoanon. For Christian art, it is also important that such symbols always assume a geometric figure. The very beginning of all creating lies in the geometric, not only of the human creating but also of the one of nature.

2 Only a completely new sensation, as it ventures into religious life with the Holy Frances and the mystics, whose roots, however, lies in France [mushroomland -mh], has given religion yet a new creative power in the area of visual arts.

Page 5

for symbolization, takes its way from the naturalistic to the abstract-geometric. The crafty /manual simplification of the form repertoire has been mentioned already. Now the clerical literature of the visual arts dictates their objects, also the tree type is influenced by the new circle of imagination and soon the vegetative will shrink to the vine* and the palm tree.

[sic, mistranslation; Brinckmann here wrote ‘grapevine‘, not ‘vine’; he wrote ‘Weinrebe’ here. Now when we say “grapevine” instead of feeble generic “vine”, this places us squarely into Dionysus’ domain; Mythemeland. {vine} is important to depict non-branching; e.g. Jonah’s gourd plant; gourd = vine. -mh]

From the agricultural connection, in which the antiquity gave the palm tree, the palm tree is now taken out. Its trunk becomes stiff and is covered with excessively big scales, the fronds lose their fine-drawn riffles in the sarcophagus [important {carved into rock} mytheme -mh] reliefs and radially shoot out of the stem head in form of a scythe blade. The grapes that hang around the crown in form of a wreath will be reduced to two that will hang down on both sides, pressed flat.

The area/surface character of the art is crucial for the use of the palm tree. Architecture offers examples in the development of the capital: the Corinthian-Roman flattens/levels and the end of the series is the Ravennatic-Byzantine fighter capital with its pure one-dimensional linear ornamentation. Christian art loves to at first give fix end points to a surface/area, e.g. armchairs, cliffs, doors, while the rest is equally filled or distributed/divided again, such as by means of putting columns with architrave or round arch. Trees, especially palm trees, are also categorized into this principle that is inherent in the surface/area. The initial traces of a marginal lining with trees are found to be a good composition element already in the presentation of Orpheus of the Calixtus catacombs, for a marginal lining with palm trees almost each apsis mosaic gives examples in later times. The narrow room, the bending after the crest of arching/bowing modify the already favorable shape of the palm tree. On the one hand, the fronds are not simplified as strongly as in the plastic as a consequence of the size of the presentation, also the number of the trunk

1 compare Riegl. Questions of Style (Stilfragen), Berlin 1893, also Semper, Style (Stil) II, Volume 8, 496.

Page 6

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n13/mode/2up

scales is not that coarsened, the sphere-shaped bush of the crown, however, as it is still given in S. Cosma e Damiano (530), is dragged/protracted and appears with the scarce residues of some stretched-up-high fronds in the apsis mosaic of S. Pudenziana (390) (II, 3).1 [Plate 2, diagram 3]

The development that the palm tree undergoes in its substitution for separating columns is strange. One can name the country house ornaments of S. Apollinare nuovo (580) an example for this insinuation, in which a saint and a palm tree alternate, respectively, and also the cupola mosaic of S. Maria in Cosmedin of Ravenna. The sarcophaguses, especially the Ravenna ones, again, offer good examples. 2 The insinuation of an originally vegetative form instead of an architectonical limb means a loosening of the architectonic idea; it is consequent if the architectonic idea of the column grows into the vegetative form, which is no longer corrected by nature. The palm tree is being architectonized. Its smooth, straight trunk, [nonbranching -mh] the breaking out of the crown at a sharply separated place [sharply contrasting branching -mh] , especially the bending out of the fronds on the side, which close into a semicircle from two neighboring trees, make them appropriate for this. First of all, a disk-shaped limb moves between trunk and crown, comparable to the capital, toward the place that also nature draws by means of died leaf roots and bass/velvet matter (II, 4).3 [Plate 2, diagram 4] A doubling of this disk with an in-between piece appears (II, 5),4 [Plate 2, diagram 5] and whereas the fruit grapes were hanging down from above over the disk rim before, here three little fruit stems with one berry each arise from the in-between piece. The scales of the trunk are initially small and in many rows; they stretch out lengthwise at sometimes in tilting waves and pieces of rock, [{rock} mytheme = block universe -mh] sometimes seeming to be little boards that are nailed upon,

1 In these days of traditions, the chronological sequence is not essential for the development of a form. Old motifs are long repeated, and a later piece may be consulted as an example for an earlier form stage.

2 Garacci, table/panel 334, 341, Deciduous Trees in similar application table/panel 350, 379.

3 As an example very instructive, a Ravenna sarcophagus, picture

Venturi, Storia dell’arte italiana (History of Italian Art). Milan 1901, figure 200, Garucci, table/panel 345, whose palm form is also proof for the following. (II. 4.) [Plate 2, diagram 4]

4 Garucci, table/panel 356.

Page 7

pointed in an angular shape, and they make the trunk appear like a channeled/chamfered column shaft.1 Finally, a purely architectonic creation appears, which denied the organic growing of the tree out of the earth; the trunk is insinuated to have a column basis. The palm tree, the Christian tree, has become an area composition limb and has gotten into architectonic connection. Its shape and detailing has become simplified into a crafty type, it has even lost its purpose to connote that a process is taking place outside.

In the next chapter, the evaluation of a botanical denomination will be closer looked at. From the already mentioned aspects, it can be concluded that it cannot depend on an individual denominating, and that only the first forms of the series show that the basis of the schematic creation is the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera)2 that also grows in Italy but does not bear ripe fruit.

1 Another stylization type appears in Ashburnham/Pentateuch: the trunk put together out of a series of spheric limbs.

2 Compare Viktor Hehn, Cultural plants VIth volume, Berlin 1894.

[check Archive.org pages to see if plate I-IX is referenced in the text -mh]

Chapter V: New Forms

pages 33-47 not present (15 pages)

Page 48

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n55/mode/2up

top third of page omitted

* * *

From the pages of this book, one will be able to read a certain dryness despite its polemic. There is a type of presentation in history of art that needed to be fought against, which sees a slow but consequently intended development toward nature, a striving to reflect the forms of the environment in images, in the entire medieval painting, and whose conclusion always is: how close has one gotten to the role model nature? However, tradition and the feeling for style are the crucial factors here, next to which a sporadic, rare nature motif is of no importance. One does not want to depict nature! Such a victorious desire consciously appears only in the XIVth (fourteenth) century and it is unjust to judge everything beforehand in terms of the achieved nature truth or to grasp the development under the aspect of the aspired naturalism. Due to a miniature, only a limited conclusion can be drawn onto the general nature feeling, because a sensation for the surrounding nature is a mood condition that does not need detailed observations, the dreamed shapes and colors of poetry say more than a meticulous drawing. The main mistake of millenniums of striving for naturalism, on which

1 Irmer’s opinion, for example (a.a.O., page 37), there would be Alpine roses in Cod. Balduini, is wrong.

Page 49

judgments were built, could only come into existence in times like ours, [1906 -mh] which felt the urge of a vivid style so barely and which say the saving rope in naturalism. There is something higher than a copy of the appearance flight: the form-making/building style. And a painter who creates out of an art that is strong in style, [evidence-type: stylized depictions of mushrooms (often also highlighting themes of {branching vs. non-branching}) -mh] does not go to nature and builds then, but he rather develops existing forms according to psychological laws of a timely and racial [ie the Valentinian “race” of Pneumatics -mh] predisposition, from his sphere of existence.

Only later one begins to not only see nature and express one’s joy about her in poetry but also to orientate oneself toward her in terms of image presentation. Nature becomes a subtle admonition/warning for art not to get lost in abstract images. One said that for the medieval artist, all nature forms changed into an ornament style right away upon its reflection.2 This is not correct. The miniator has his pool of forms that suffices for the iconographically relevant presentations, he does not need nature; [au contraire, the images bend toward accurate naturalistic depictions of nature: of mushrooms -mh] only the continuous repetition of traditional forms explains their abstraction. The slow approach of art toward nature is not to be seen as a loss of the striving for ornamentalization but the continuous development of an originally ornamental form is now influenced by the remembered images of nature. [much hypothetical theorizing here; driven by what 1906 model of psychology & history? -mh] The stylization drive does not stop but formations that are strictly following a certain style grow/enhance into naturalistic ones. The development went on during one millennium from the ornamental to the ornamental, now it moves from the ornamental to the naturalist. Thus, the heart leaf (grass-of-parnassus) develops into a basswood leaf, the often mentioned double lily develops into an oak leaf. The Bamberg Alkuinvulgata uses this double lily as a room/space leaf. In the Paris

1 Constructions such as the figures Berensons over the Dante only remain thought-of constructions. The feeling, sensing “seeing” of the poet is different from the reproducing seeing of the painter.

[“reproducing”? It is debatable whether the goal of the religious painter is to “reproduce” — to reproduce — or to depict, what?

To “reproduce”, ie depict, the mushroom and its effects re: an experiential mental model of time, control, and possibilities branching?

Or to “reproduce” and depict a literal tree?

Which goal makes sense to “reproduce” ie depict?

Answer: The mystical experience, not the literal botany of trees, which is rather irrelevant. -mh]

2 Out of this unilateral perspective came the book written by Lambin, Lafleure gothique, Paris 1893. When consciously gives naturalistic leaf motifs, the early gothic certainly still geometrizes these into a regular appearance, yet it seems foolish to also develop the double lily from fern and the palmette (already Byzantine) from the lily.

BRINCKMANN

Page 50

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n57/mode/2up

Cod. lat. 10474 (II H XIIIth century), in the Cathedral of AGurk, this leaf appears still with a bent, pointed/pulled-out tip. This becomes more and more round, such as in the Bresual Missale nocturnum and the Vienna Parzival, yet in a conscious manner, the oak leaves only appears with acorns in the Manesse song manuscript, in further development toward nature, although nothing is observed here in terms of the structure of the oak tree trunk, but the naturalistic leaves and acorns grow out of an tendril/creeper tree [important non-branching mytheme -mh] (V, 10, the six forms among each other). [Plate 5, diagram 10]

The reason for this development is partially to be found in literature, which always precedes painting. [if you say so; seems debatable -mh] The demand to present something non-traditional at first brought seen nature into the picture (compare: the incredible rabbit of the Carmina Burana, VIII) and once taken on, it also influences the traditional types. Then, however, this inclination toward naturalism is explained out of a change in the optical seeing. The French early gothic has paved the path in this context. Before, one encountered a closed matter, a closed contour/outline, but now the drawing of lines has a tearing/ripping effect. This appearance is apparent both in the silhouette of a French castle, as in the shoulder/banding of a manuscript. Also, the calm, straight surface is irritated by light and dark. The smooth pillar column is made vivid by means of little columns that are stuck/glued to it, the vertically grooved/furrowed pillar is created. Sharp cuts into the silhouette, agitation in the surface, are apparent in the leaf decorations on the embrasures and intrados of Gothic cathedrals of the XIIIth century. The joy of formal irregularity now let the role models or images of nature jump in, which were avoided in former times just because of that reason. The thorn, vine leaf, and English holly now become favorite motifs of the architectonic decoration and book bandings. Sharpness of drawing and realism of the material structure, feeling for the organic in the leaf approach and in grouping the leaves are astonishing in the plant decorations of the cathedrals of Paris, Reims, Bourges (XIIIth century)1, they often seem like a cast/mold/replica over nature. And all this very sudden,

1 Compare Vitry et Briere, Monumente (Monuments). At the beginning of the XIVth century, this decoration again becomes more ornamental, more symmetric, and more abstract.

Page 51

only because one wants it like that. This naturalism does not have such an effect on painting in general.

The French sculpture does the first step in the beginning of the XIIIth century to come from the area/surface into the space.1 This problem is energetically taken on by Giotto in a picturesque manner, the artist who continues Giovanni Pisano’s ideas, who creates the connection with France. In Giotto, the individual appearance loses softness with the spatial seeing and imagining, which the painter Cimabue still gave in manual tradition of the former illusionism. Everything becomes a fix body in the room/space. The individual leaf sections of Cimabue’s trees become spheric balls, which are positioned not only next to each other but also in front of each other, and thus let the crown appear as a three-dimensional body. The trunk is smooth and stiff, [nonbranching -mh] even if it strives for a natural creation in its structure and surface. Vasari’s honor title “buono imitatore della natura” can claim validity only to a limited extent, the vegetation is generally quite scarce [the goal is depict mushroom & branching vs nonbranching -mh] and a strong tendency towards generalization becomes apparent. Far more realistic are the Sienese, and Ambrugio Lorenzetti almost gives a landscape for its own sake in the ager publicus. These little Giottesk-Sienese on small straight stems [non-branching -mh] are the ones that represent the tree for a long time to come.

In the course of the XIVth century, Italian influences lead to a decisive change in French painting. Dvorak2 has indicated some ways – Avignon (since 1335 painting of the palace by Italians) and Naples2 (Karl of Anjou). The Sinese-Giottesk presentation of space pushes the drawing/spatial/surface style of early gothic away. It is as if the ability of a naturalistic detailing would suffocate. In the Munich Passion de notre Seigneur Jesus Christ (gall. 32, XIVth century), in the Vienna Romant de la Rose (gal. 2592, end of XIVth century from Guillaume de Lorris

1 W. Vöge, The Beginnings of the Monumental Style. Straßburg 1894.

2 Illuminators of Joh. V. Neumarkt, annual book of the holy imperial palace, volume XII.

3 Compare Bertrauf, Sta. Maria di donna regina, Naples 1899.

Page 52

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n59/mode/2up

and Jean Clopinel de Meuny) appear the Sienese-Giottesk spheric trees,1 next to them also the leaf crown tree, only the bandings continue to spin their naturalist tendrils. Also, in mural painting, the spheric tree is the only form, such as in Runkelstein (beginning XVth century)2 and in the Castello di Manta nel Saluzzese (beginning of the XVth century)3, here already with a more vivid silhouette.

There was a need for other artsy personalities who were neither dreamers nor visionaries, did not bring forward accomplishments in poetry nor in philosophy, whose lymphatic temper and reality sense enabled them to submit themselves completely to the things: the Dutch. “They did not know how to simplify nature; they needed to reproduce it in its entirety”,4 they evaluated each of its appearances equally/in the same way. The space was seen, the naturalistic detail observation was made, the Dutch combine both: their painting is no longer the image expression of the word beside it by means of some scarce requisites, it is an excerpt from nature. The willingness toward it appears in its highest expression in Dutch painting of the XVth century.

1 Still in the Munich cod. gall. 7 “Bagnanut de Montanban”, written by David Aubert with miniatures of Loyset Lyedet from 1462, the sphere tree is used, and the simultaneous German art challenges with it and the barren tree its entire stand of trees.

2 Freakenoyklus from the Castle of Rankenstein by Bozen, taken from Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck 1857.

3 Compare essay by d’Ancona, L’arte, 1905.

4 Taine, Philisophy of Art, Paris 1865. The essay by Dvorak, “The riddle of the Art of the Brothers van Eyck”. Almanach of the Holy Emperor’s House Volume XXIV, confesses on page 249: “About the whereabouts of the art of Hubert, we know as little as how Jan’s new conception of the loyalty to nature came into existence.” Let us go with Taine, who does not want to solve riddles, but who sees the power of inexplicable race idiosyncrasy.

[We can explain the “race” of the Pneumatics, esotericists, per Valentinian gnosticism: they experience and depict “analogical psychedelic eternalism/pre-existence” of control-thoughts, as opposed to apparent branching possibilities steered among by King Ego.

The experienced & altered-state-perceived pre-existence of personal control thoughts kills the egoic model of time & control. -mh]

/ end of translation

Full-Text Search of ‘Pilzbaum’ in the Book

Copied from:

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2022/03/09/idea-development-page-13/#Ep99-Psilocybin-Wins-Everything

– research done around April 2, 2022: (good content I wrote there, find ‘pilzbaum’).

Full-text search of Brinckmann’s 1906 book Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings, for ‘pilzbaum’ (mushroom trees)

Brinckmann’s book that’s cited by Panofsky in letters to Wasson has 5 hits on “pilzbaum” (mushroom trees): https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/mode/2up?q=pilzbaum

page 23, 25, 33, 43, 46

I right-clicked on the hits passages, Translate to English, per below.

Hit 1: Page 23

Page -23-

First and foremost, one ties in with the illusionistic painting style.

One of the rare intermediate uildeL of the Ashburnham Pentateuch fs. p. 11), which Springer* regards as the preliminary stage of Carolingian painting.

On the sheet with the representation of the first parents there is the palm tree, then a tree consisting of three flame-like bushes, which goes back to the lancet tree, and a kleuierPilzbaumwith three mushroom-like

Hit 2: Page 25

The Kvangeiiar Franz !!. Paris national lat mid IX. .Ihh.), whose ornauienlaier Scliniuck in foreign countries is a counter salt to the soDätigen painterly treatment, brings back thePilzbaum, but already greatly changed (IV, 5).

The trunk is long and twisted at the bottom, the crowns in the form of half circular discs, one or two of which sit on the trunk, are covered in rows with shaggy tails, a transformation of the leaves, the lower edge forms a row of spots:

an urge to The palm tree is formed by a quiver-like trunk ^ with asl stumps – without knowing the foreign form, one can transfer them to the peculiarities of the native cottages – from which several fronds and the hanging grapes grow tll, T).

The cone is particularly rich around with many ledges in the crown decorated with polka dots and never-ending small side-cuts.

Trunk and crown still achieve a three-dimensional effect through the correct setting of shadows.

Hit 3: Page 33

Vöge’ has worked out a workshop of this time in an exemplary manner, which appears very clearly and large in form and composition.

Before working out, working into the context of time receded, and so this school of painting lies there as a solid block, but isolated.

The constantly recurring HauMirunii of these so-called Liulhaiy^nipiK’ is a (lreik(‘)|)figure, flatly archedPilzbaumwith a gnarled little thread that twists at the bottom and is now covered with eye buds i.sL (VH).

Already in (Index Kgberti liatte the Filzkitj)!’ the rope ends curve slightly upwards, but the flatness is what stands out here, and only contemporary Byzantine art offers similar features.*

Two small berries often hang down from the mushroom heads, each on a thread stalk, a shinuck that was already popular in Carolingian times (II, 10) , which has also crept into the ornaments as a delicate filling.

The eye buds are naturalistic transformations of the spiral bones, often unchanged spirals are drawn at this point, which also appear elsewhere, when the trunk is turned – the base also resembles a twisted rope, as in the Evan^reliar Otto III. (Munich lat.

Hit 4: Page 43

room that sounds dark, so to speak, dm (iriind for the bilfields: the S il ho uet t eri building iii.

Excellent examples from the 12th century are offered by the stained glass of the cathedrals in i^ens (III, 6)’ and Le Muiis .^

The decisive word for this formation will have been the technical requirements of glass painting[Panofsky’s photostat?]: the enclosing of larger compartments with lead rings overall form is pursued: the B1 ä 11 e ronbau ra.’

There is also evidence for this in Sens, but the stained glass in Le Mans Cathedral reveals the origin of this form from thePilzbaumand thus give the important instruction ‘VI, 1 .*

The trunk is curved in an undulating manner, the mushroom tip grows out of an ornamental leaf calyx on three stalks.

which already richly adorned Carolingian miniators and which liier du iit is exposed with ore leaves.

This dense filling with Hlällerri is the design outline to which the later pen drawing is linked, the dark overall outline of the unifying lead border remains unnoticed.

The windows of the triforium, which come from a somewhat later period, give the pure leaf crown tree.

Beautiful and rich examples from the beginning of the XIII. Century can then be found on the stained glass windows of the Cathedral of Bourges. *

Even later, especially a Paris codex (Bibl. nat. lat. 10474, IL H. XIII. c.) gives pure and noble formations of this tree scheme VI, 10).

Hit 5: Page 46

Page -46-These forms of the silliouette tree, the crown tree, and the pine cone tree, which originated in France, invaded Germany shortly before 1200.

The previously so popularPilzbaumdisappears and is found only very small, as in the vault paintings of the Decagon of St. Gereon, Cologne (after 1219) (IV, 13)’ and in the Carmina burana.

On the other hand, the purely ornamental forms survived for a longer time as tree symbols and later as plant symbols.

Characteristic is the representation of the Carmina burana (fol. 64) (VIII), which illustrates the following verses:”

Acknowledgements

Cyberdisciple found and provided the archive.org link to Brinckmann’s book, and the art historian reference entry about him.

Dr. Jerry Brown provided the English translation of Chapter 1 and the final quarter of Chapter 5.