Michael Hoffman, January 7, 2025

Contents:

- Browns’ Comment: Ramifications of Publishing Panofsky’s Letters

- Huggins Uses Panofsky’s Two Letters, Including Brinckmann Citations, Out of the Blue – As if Nothing Amiss

- Wasson’s Repeated Censorship of the Brinckmann Citation, at the Same Time as Berating Mycologists for Failing to “Consult” Art Historians

- pilzbaum: A term coined by art historians by 1906 that means trees that look like mushrooms

- Art Historians Are in No Position to Insult, Lecture, Berate, and Chastise Mycologists

- Huggins’ Dismissive Label PMTs (Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists) vs. PMDs (Psychedelic Mushroom Deniers), like Hatsis’ Construction “Secret Amanita Cult Theorists”

- Branching (and Non-Branching) Indicates Psilocybin Mushrooms

- How Did Huggins Find Out About the Censored Panofsky Letters?

- Huggins tries to excuse Wasson’s obstructionism

- Art Historians Misread Trees as Merely Peripheral and Not Worth Writing About

- Wasson Perverts the Meaning of “Consult” Art Historians, from Library Research to Personally Contacting

- The Argument from Celerity: Scholarship by Measuring the Quickness and Strength of Disavowal by Authorities

- Citations Mysteriously Missing from the Bibliography of “Foraging Wrong”

- Argument from Insulting Mycologist as Ignorant of What the Authorities Say

- The principle of artist responsibility and freedom — including the “special exceptional topic” of mushroom-trees

- Huggins Uses the Arguments from Wasson and Directly from Panofsky’s Letters, and Is Therefore Held Accountable for Wasson’s Censorship

- pilzbaum (trees that art historians describe as “look like mushrooms”) don’t look like mushrooms, because they have branches — that look like mushrooms

- Gills and Veil Look Like Branches

- Art Historians Deserve to Be Ignored and Disrespected, Having Written Nothing Related to the Mushroom-Trees Question

- Terms

- See Also

Browns’ Comment: Ramifications of Publishing Panofsky’s Letters

In a Comment on my page “Erwin Panofsky’s Letters to Gordon Wasson, Transcribed”, Prof. Jerry Brown & Julie Brown thanked me for explaining how major the Browns’ breakthrough was in publishing both of Panofsky’s letters that Wasson censored from 1952-1986.

Dear Michael,

While we realized the importance of publishing the two Panofsky letters to Wasson side-by-side, you have obviously grasped and illuminated their greater importance in the entire Mushrooms in Christian Art debate. In our opinion, there is no debate.

Due to the focus and interpretation you’ve brought to these letters, we consider their discovery at the Wasson Archives and our subsequent publication to be one of our most significant discoveries – along with the documentation of Wasson’s meetings with the Pope during his time at JP Morgan which handled Vatican accounts; and, of course, the extensive images of both Amanita muscaria and psilocybin images in Christian art published in The Psychedelic Gospels.

Thanks for acknowledging our work in your post,

Julie and Jerry Brown

Huggins Uses Panofsky’s Two Letters, Including Brinckmann Citations, Out of the Blue – As if Nothing Amiss

Regarding Erwin Panofsky’s 1952 Letters to Gordon Wasson, published by Brown & Brown 2019, transcribed by Michael Hoffman, 2023.

In his 2024 article “Foraging for Psychedelic Mushrooms in the Wrong Forest”, Ronald Huggins thinks he can leverage and cash in on the Panofsky letters and their Brinckmann citation (discovered & published by Brown, not acknowledged by Huggins) without paying for the scholarly sin and crime and con artistry committed by Gordon Wasson, the Father of Obstructing Ethnomycology.

Wasson’s Repeated Censorship of the Brinckmann Citation, at the Same Time as Berating Mycologists for Failing to “Consult” Art Historians

Since 1952 until the end of his life in 1986, Wasson repeatedly, covertly, and deceptively censored Panofsky’s letters to block research, at the very same time as pretending to call for more scholarly consultation of art historians.

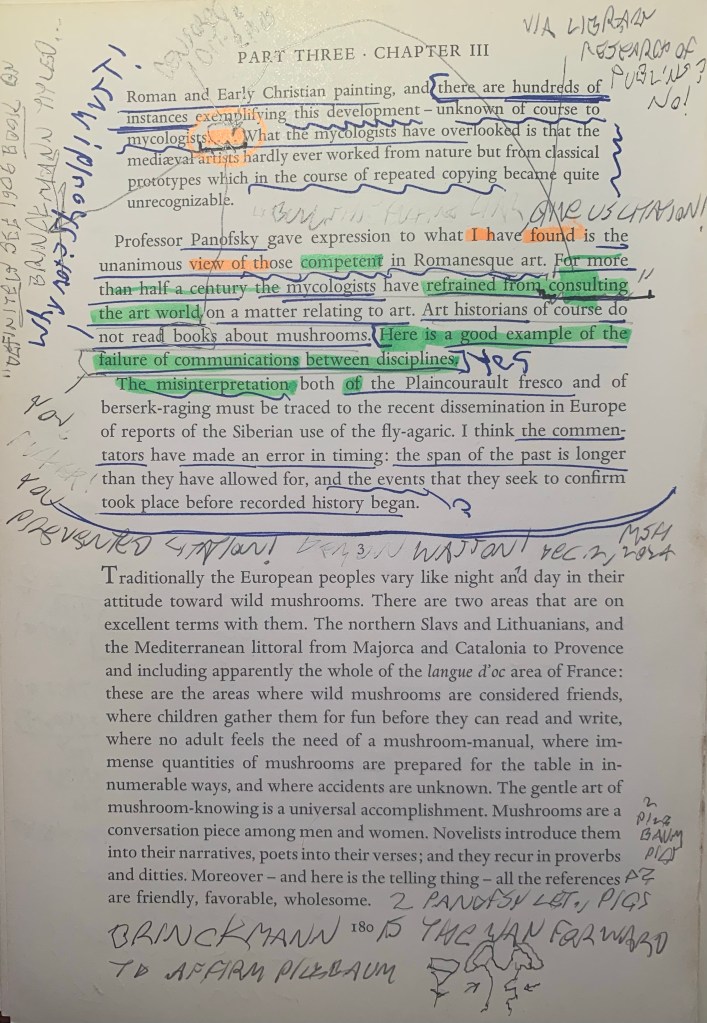

On page 180 of SOMA (1968), Wasson bluffs and censors the double-strong citation of Brinckmann (1906) by Panofsky (1952) while simultaneously insulting mycologists and berating and chastising them to “consult”.

Compare:

- Line 3 of the Panofsky excerpt, “unknown of course to mycologists. . . .“

- Line 3 of the next paragraph, “refrained from consulting the art world”:

Here’s Panofsky’s actual letter, around Wasson’s ellipses:

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2025/01/07/panofskys-letters-to-wasson-transcribed/#Sentence-1-5 —

“It comes about by the gradual schematization of the impressionistically rendered Italian pine tree in Roman and Early Christian painting, and there are hundreds of instances exemplifying this development – unknown, of course, to mycologists. If you are interested, I recommend a little book by A. E. Brinckmann, Die Baumdarstellung im Mittelalter (or something like it), where the process is described in detail. Just to show what I mean, I enclose two specimens: a miniature of ca. 990 which shows the inception of the process, viz., the gradual hardening of the pine into a mushroom-like shape, and a glass painting of the thirteenth century, that is to say about a century later than your fresco, which shows an even more emphatic schematization of the mushroom-like crown. What the mycologists have overlooked is that the medieval artists hardly ever worked from nature but from classical prototypes which in the course of repeated copying became quite unrecognizable.”

Also, from Panofsky’s 2nd letter to Wasson: https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2025/01/07/panofskys-letters-to-wasson-transcribed/#Sentence-2-10 – [handwritten:]

“Please keep my poor little pictures as long as you wish. And I really recommend to look up that little book by A. E. Brinckmann.“

Wasson replaced the highlighted content by ellipses while at the very same time berating mycologists as ignorant and needing to “consult” art historians, as a pretense; a bluff; a put-on; an affectation, to deceive and obstruct investigation.

Wasson in 1952 or 1953 refrained from informing the leading mycologist John Ramsbottom about the Brinckmann citations, and about Panofsky’s two included art works showing mushroom-trees, at the same time as calling mycologists ignorant and needing to “consult” art historians.

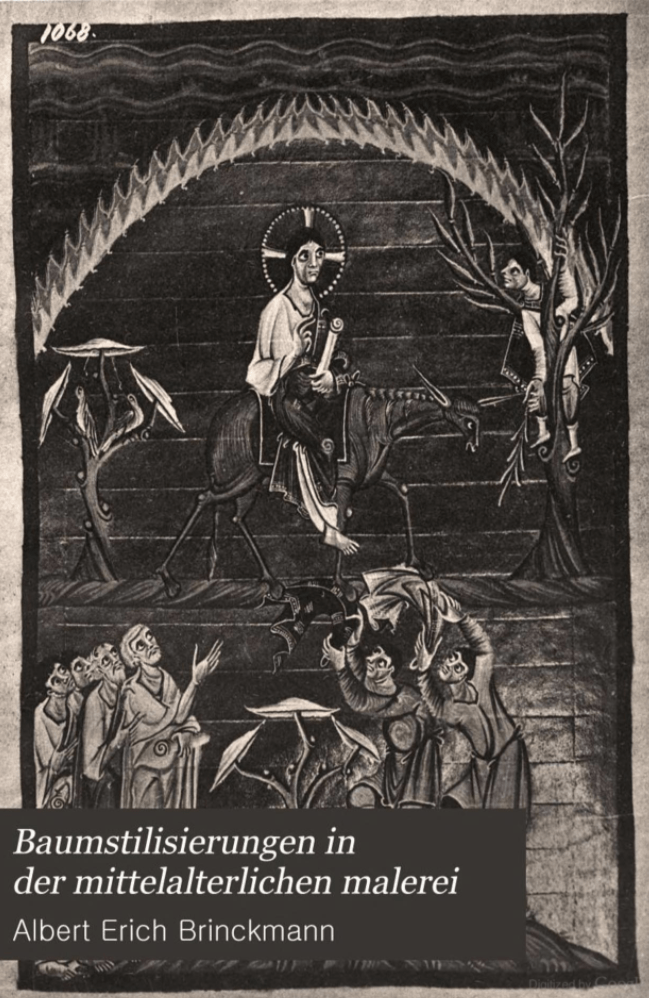

Huggins then in 2024 tries to use the censored material as if we’ve had it all along: “Trees … are not often discussed by art historians. A noted exception is Albert Erich Brinckmann’s Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen Malerei (1906), a work recommended by Panofsky in his letters to Wasson back in 1952.”

(“Probably no one will notice this use of the Panofsky letters & Brinckmann citation, out of the blue.

“I’ll just amplify the Wasson/Panofsky move of severely insulting, chastising, and berating mycologists, as a distraction strategy.” – thinks Huggins.)

John Ramsbottom’s retaliation to such insults was to re-print his new book in 1953, with an added citation from Wasson exposing him as a committed sceptic, and of a rude sort, using words such as “ignorant”, “blunder”, and “unaware” in Wasson’s multiple such writeups:

Rightly or wrongly, we are going to reject the Plaincourault fresco as representing a mushroom. … For almost a half century mycologists have been under a misapprehension on this matter.

Wasson to Ramsbottom, letter of December 21, 1953, reprinted in Ramsbottom, Mushrooms & Toadstools, post-1953 printing, p. 48. Found by Irvin 2006.

pilzbaum: A term coined by art historians by 1906 that means trees that look like mushrooms

The term pilzbaum, German for “mushroom-trees”, means trees that look like mushrooms, in Christian art. The term pilzbaum was coined by and used by art historians; it is their term.

The term pilzbaum has been used by art historians since before the concept of psychoactive mushrooms, such as 5 times by Albert Brinckmann in his 1906 book Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings.

pilzbaum deniers are scholars who deny purposeful mushroom imagery in Christian art; deniers of mushroom imagery in Christian art.

Art Historians Are in No Position to Insult, Lecture, Berate, and Chastise Mycologists

Deniers of mushroom imagery in Christian art have garnered for themselves all the credibility of a con artist, and are hardly in a position to lecture and berate others for not consulting the art historians – committed skeptics who deliver nothing but a worthless argument from authority by people who’ve never written or published anything about trees or the mushroom-trees question.

The lone, single, “little” publication covering mushroom-trees was censored by Wasson.

You’re telling me I should consult art historians? I’d love to! That’s what I am trying to do: read their writings about mushroom-trees.

So where is the citation that Panofsky must have provided to you, Wasson?

I wanted to properly consult the published works of art historians on this topic of mushroom-trees, but just as I suspected in 2006, confirmed in 2019, there are no such writings — or pathetically few, and old, and “little”.

Wasson hid for 67 years (1952-2019) the single publication by art historians that contains passages about mushroom-trees – from 1906, before the concept of psychoactive mushrooms even existed for art historians.

Huggins’ Dismissive Label PMTs (Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists) vs. PMDs (Psychedelic Mushroom Deniers)

Ronald Huggins’ term Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists is like Hatsis’ Construction “Secret Amanita Cult Theorists“, but Huggins adds a acronym form.

This is fair, “for convenience in discussion”, except that Huggins strangely omits this type of label for his own side’s position, breaking parity.

“For convenience in discussion” is Panofsky’s phrase for the purpose of neutralizing the fact that art historians use their term pilzbaum, mushroom-trees.

~~ link to sentence by Pan

http://egodeath.com/WassonEdenTree.htm#_Toc135889190 –

“Rightly or wrongly, we are going to reject the Plaincourault fresco as representing a mushroom.

“This fresco gives us a stylized motif in Byzantine and Romanesque art of which hundreds of examples are well known to art historians [CITATION FUCKING NEEDED!!], and on which the German art historians bestow, for convenience in discussion, the name Pilzbaum.

It is an iconograph representing the Palestinian tree that was supposed to bear the fruit that tempted Eve, whose hands are held in the posture of modesty traditional for the occasion.

For almost a half century mycologists have been under a misapprehension on this matter. We studied the fresco in situ in 1952.”

– Wasson, private letter of December 21, 1953, quoted in Ramsbottom, Mushrooms & Toadstools, post-1953 printing, p. 48

As if to avoid parity between the positions in dispute, Huggins doesn’t provide an equivalently distancing name or acronym for his own team’s position, such as: Psychedelic Mushroom Deniers (PMDs) – deniers of mushroom imagery in Christian art.

PMTs = Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists; pilzbaum affirmers. Huggins’ term in his “Foraging Wrong” article, 2024.

PMDs = Psychedelic Mushroom Deniers; my term countering Huggins, describing his own camp in a slightly diminishing, dismissive way.

Branching (and Non-Branching) Indicates Psilocybin Mushrooms

I’m glad to see Huggins latching onto Panofsky’s branching argument, hidden from us by Wasson since 1952.

I’m more of a Branching Theorist than a “Mushroom Theorist”, in the sense Huggins means.

What we should be looking for is not just “mushrooms” in Christian art, but rather, combined {mushrooms}, {branching}, {handedness}, and {stability} motifs.

That’s the message that artists are sending via this genre, a message that’s more about branching (as a Psilocybin effect), rather than focused just on mushrooms.

The message of the mushroom-tree artists is that:

On mushrooms, switching to the non-branching worldmodel avoids the threat of loss of control. Reject branching possibilities (while on mushrooms), to avoid the threat of loss of control, and have stable, viable self-control.

the mushroom-tree artists

Branching features, including emphasis of non-branching, in conjunction with {handedness} and {stability} motifs, prove that mushroom-trees positively do purposefully mean mushrooms.

How Did Huggins Find Out About the Censored Panofsky Letters?

The next sections are from my comment:

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2025/01/07/panofskys-letters-to-wasson-transcribed/#comment-2449

Mystery intrigue from a novel by Brown, Brown, & Brown:

How did Huggins’ “Foraging Wrong” 2024 article find out about the two Panofsky letters in drawer such-and-so, if not from Brown 2019, and why does it cite only Brown 2016, not 2019?

Huggins wrote about how we actually cannot “consult” art historians’ publications about mushroom-trees, because these competent art historians who are so thoroughly familiar with mushroom-trees have never published anything on the topic, which is of mere peripheral importance:

“Trees, being peripheral to the more central features of medieval iconography, are not often discussed by art historians.

“A noted[!] exception is Albert Erich Brinckmann’s Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen Malerei (1906), a work recommended by Panofsky in his letters to Wasson back in 1952.”

Brinckmann is so “noted” by Wasson in SOMA‘s Panofsky passage in 1968, and by Wasson 1952-1986, that Wasson censored, omitted, and never once mentioned Brinckmann’s name or that Panofsky twice, strongly recommended his book Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings.

AS IF scholars and mycologists have had access to Panofsky’s letters (both citing Brinckmann) since 1952 or 1968!

AS IF we (Brown) didn’t just find the Brinckmann citation and recognize its importance only recently, in 2019!

And how does Huggins expect anyone to use his useless, unhelpful citation of drawer such-and-so at Harvard?

Wasson and Huggins both use improper, abnormal dancing-about, instead of normal scholarly publications and citations that are usable by scholars.

Did Wasson read the publications of “competent” art historians, per normal scholarship?

No; Huggins promotes instead of library research:

“Wasson readily sought help from people with expertise in fields related to his research.”

“Sought help” from “experts” who never wrote and published on the topic of mushroom-trees, and consider trees merely peripheral, not central in importance, and not worth bothering to write and publish about.

Huggins tries to excuse Wasson’s obstructionism

Huggins tries to excuse Wasson’s obstructionism:

“Given Wasson’s importance the PMTs [Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists] are generally aware of Panofsky’s warning, and of Wasson’s subsequent remark that “mycologists would have done well to consult art historians.”

“But they reject it as “an unreflective dismissal [that] misses the point,” or a case of Wasson’s being taken in by the “monodisciplinary blindness and interpretive slothfulness of professional researchers,” meaning Panofsky and the other unnamed art historians Wasson consulted.

“One prominent PMT [Psychedelic Mushroom Theorist], J.R. Irvin, even complained that “Wasson adopted Panofsky’s interpretation and thenceforth began to force it upon other scholars.

“Uncritical acceptance of the Wasson-Panofsky view lasted, unchecked, for nearly fifty years.” [Irvin, THM]

“It might be noted, however, that many of the works in which the PMTs [Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists] express contrary views were published during the fifty years to which Irvin refers.”

Art Historians Misread Trees as Merely Peripheral and Not Worth Writing About

Where are the expert art historian’s works in Huggins’ Bibliography, that discuss the question of mushroom-trees (trees relevant to the Wasson-Panofsky view)?

There aren’t any (or, as I wrote in my 2006 Wasson article, we can conclude that such writings by art historians are pathetically few and weak); as Huggins admits:

“Trees, being peripheral … are not often discussed by art historians. A noted [read: censored] exception is Brinckmann…”

As Huggins says, the “many works” about mushroom-trees are from mushroom-imagery affirmers, not from mushroom-imagery deniers (art historians) regarding the mushroom-trees question, whose studies on this topic are nonexistent.

Even Brinckmann’s “little book” from 1906 (that’s all you got?!) is missing from Huggins’ Bibliography section.

In 1996-1998, Georgio Samorini finally followed what little of Panofsky’s lead (that there are hundreds of instances of mushroom-trees) that Wasson in SOMA let leak through.

Wasson Perverts the Meaning of “Consult” Art Historians, from Library Research to Personally Contacting

Wasson perverts the meaning of the word ‘consult’, from consulting the writings of art historians about the mushroom-trees question, to personally contacting art historians to question them on their stance on this prohibited topic.

Since Wasson couldn’t win by citing Brinckmann’s “little” book (written before the concept of psychoactive mushrooms) and by showing the two mushroom-tree pictures that Panofsky sent to him, which would invite further research and a positive conclusion about mushroom-trees, he tried to change the rules of the entire standards for doing academic research, to prevent investigation.

Huggins continues:

“The only real advantage Wasson has enjoyed was perhaps the result of his [formerly] trusted reputation, based partly on his willingness to engage scholars in other fields as a way of cross-checking his own work, a feature not often encountered in the more generally insular PMTs [Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists].”

Normal scholarship uses writing and publication and citation as a way of doing the above.

Why require this special approach of “reach out and consult competent authorities to measure their speed and strength of disavowal”, for the special, exceptional topic of mushroom-trees, only?

“In the meantime, the few art historians with expertise in Ottonian and Romanesque art who are aware of the PMTs [Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists] claims continue to echo Panofsky.”

How can art historians “echo Panofsky”, when they’ve only had half of one of the two letters which Huggins somehow has full access to? (Except the two attached art works.)

Art historians have only had access to the two letters starting in 2019 (thanks to Brown & Brown) – not since 1952 or 1968 as Huggins wrongly implies.

Huggins needs to differentiate between the little bit of Panofsky’s argumentation that Wasson let leak through in 1968, versus the entire two letters (sans art attachments) the Browns revealed and exposed in 2019. Which “Panofsky” does Huggins say art historians are “echoing”?

The first time art historians were permitted to see Panofsky’s “branches” argument was 2019, in the Browns’ article.

Huggins continues:

“When questioned on the topic by the writer, prominent art historian Elina Gertsman responded crisply [⏱]:

“I very much do not think that Ottonian or Romanesque imagery was in any shape or form influenced by psychedelic mushrooms.””

Argument from crispness?

Huggins does not attempt to present any argumentation provided by this authority.

From this learned, grand, prominent, expert authority on “related topics” that are related to this “peripheral” topic of mushroom-trees, we’re only given a name and credentials, along with speed and strength of professed disavowal. Scholarship!

The Argument from Celerity: Scholarship by Measuring the Quickness and Strength of Disavowal by Authorities

The Hoffman Uncertainty Principle:

The more directly you probe and interrogate publicly the competent art authority (who has published nothing on the mushroom-trees question), the quicker (and crisper!) the celerity of disavowal — and the less the certainty about the person’s actual belief.

Huggins presents a bizzarre special-case approach to this topic, only:

Consult the drawer at Harvard.

Consult your local top expert art authority, stopwatch in hand, to measure the celerity with which they disavow purposeful mushroom imagery in Christian art.

Every competent art authority: “No, no, no, no, there’s no way any credible authority affirms these mushroom-trees, no way, no how; we disavow!”

Argument by celerity of authorities’ disavowals.

There is a consistent pattern of withholding and preventing people from seeing the letters.

Huggins is of no help here: he does not publish the letters for scholars to share, and he does not point to the Brown 2019 article or my original transcription page at this site.

Citations Mysteriously Missing from the Bibliography of “Foraging Wrong”

Mystery intrigue in the Bibliography of “Foraging Wrong”:

“Consult” the competent art authorities — yet Huggins’ Bibliography lacks these key entries centrally relevant to main topics discussed in the article body:

- Brinckmann, Albert (1906). Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings. Either at:

- Archive.org.

- https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2020/12/11/brinckmann-mushroom-trees-asymmetrical-branching/ with Brown’s transcription of Brinckmann into English.

- Brown (2019).

- Hoffman (2022). Erwin Panofsky’s Secret Pair of Letters to Gordon Wasson, Exposed

- Panofsky (1952). Letter 1 & 2 in drawer at Harvard.

Argument from Insulting Mycologist as Ignorant of What the Authorities Say

The funny thing about this argument is that you can only play this card once, for a brief moment.

You cannot argue year after year, from 1952 to 1986 or 2025, that mushroom-tree affirmers are merely ignorant of the fervent disavowals of purposeful mushroom-tree imagery by (actually ignorant) art historians who have never written anything about trees (of any kind) in Christian art.

By the time of Ramsbottom’s book Mushrooms & Toadstools in 1953, and by Wasson’s SOMA in 1968, every mycologist knew quite well, all too well, that art historians are ignorant, committed skeptics, eager to disavow mushroom-trees quickly and emphatically, in order to preserve their “competent” status, while insulting, berating, lecturing, and chastising mycologists, exactly in the style of Huggins in “Foraging Wrong” in 2024.

Baloney indirection and roundabout dancing:

Huggins wrote:

“The authors venture their claims without an adequate grasp of the standard way of depicting trees and other plants in the art of the period.”

Affirmers of mushroom imagery in Christian art extremely well grasp the standard way of depicting trees and other plants in the art of the period:

Every mushroom-tree affirmer is intensely aware that art historians describe these trees as “look like mushrooms”, thus their term, the art historians’ term, “pilzbaum“, by which the art historians mean:

The trees that look like mushrooms in Christian art.

The principle of artist responsibility and freedom — including the “special exceptional topic” of mushroom-trees

The principle of artist responsibility and freedom (against Panofsky):

If the artist didn’t want art historians to think of mushrooms when seeing these trees, then the artist should not have made their trees look so distinctly like mushrooms.

Just like with every other item depicted, as art historians say on every other topic – artists were free within the genre.

Within this special topic, only, Panofsky robs artists of their freedom and forces them to follow “prototypes”, trying to remove artists’ responsibility for making viewers think of mushrooms.

The special pleading fallacy.

Huggins Uses the Arguments from Wasson and Directly from Panofsky’s Letters, and Is Therefore Held Accountable for Wasson’s Censorship

Huggins continues:

“Nor have they been much inclined to consult art historians, whose opinions on such matters they show little interest in.

“This began when PMTs [Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists] responded negatively to the advice art historian Erwin Panofsky gave to New York banker and amateur mycologist G. Gordon Wasson in 1952.”

Huggins nicely leaves out the fact that Wasson only allowed (for 51 years, 1968-2019) half of the first of the two Panosfky letters to be seen by everyone.

So much for emphatically pressuring mycologists or mushroom-tree affirmers to “consult” art historians:

Wasson and Huggins are all talk, posturing, and bluff, while withholding useful citations for critical scholarship – citations that support, not refute, the mushroom-imagery affirmers.

Art authorities have no credibility until they publish something on the unimportant, “peripheral” topic of trees (particularly mushroom-trees).

As the official voice, spokesman, and apologist for the Gordon Wasson 1968 and Erwin Panofsky 1952 argument (in both letters in full), Ronald Huggins is answerable for Wasson’s censorship of:

- The Albert Brinckmann citation (urged strongly by Panofsky, twice).

- The branches argument in letter 2.

- The two mushroom-tree art instances attached to letter 1.

Art historians have earned their disrespect, and have some answering to do.

pilzbaum (trees that art historians describe as “look like mushrooms”) don’t look like mushrooms, because they have branches — that look like mushrooms

Huggins repeats the Panofsky argument: the items that art historians describe as “mushroom-trees” don’t look like mushrooms, because they have branches. Huggins, repeating Panofsky’s newly available argument, tries to dismiss mushroom-trees because they “have branches”.

The “branches” themselves typically look like literal mushrooms. The “branches” that Huggins (following Panofsky) uses to dismiss the mushroom interpretation look like mushrooms.

If mushroom-trees “don’t look like” mushrooms, why do art historians themselves describe them as pilzbaum, mushroom-trees, since 1906 or earlier?

Gills and Veil Look Like Branches

Georgio Samorini argues that a mushroom’s veil sometimes looks like branches. As Huggins points out, this is true only fleetingly.

My better argument is that the gills and branches of mushrooms look like branches, sufficiently closely for diagrammatic, non-realistic, stylized medieval art.

Art Historians Deserve to Be Ignored and Disrespected, Having Written Nothing Related to the Mushroom-Trees Question

Art historians don’t take the topic of mushroom-trees (or trees in general) seriously enough to write and publish anything on the topic, and yet Huggins expects mushroom-imagery affirmers to take the “prominent”, “competent” authorities who published on “related topics” seriously.

Huggins expects art historians to be taken seriously on this specific topic. Why?

Respect needs to be earned and warranted, but what we’re given instead is censorship and withholding citations and art evidence.

There is every reason to not take deniers of mushroom imagery in Christian art seriously.

Terms

pilzbaum – Art historians describe, in Christian art, trees that distinctly look like mushrooms; they refer to these as pilzbaum; mushroom-trees. Brinckmann’s 1906 book contains the word pilzbaum 5 times.

mushroom-imagery affirmers (pilzbaum affirmers) – Scholars who assert purposeful mushroom imagery in Christian art. Entheogen scholars. John Allegro, Georgio Samorini, Carl Ruck, Blaise Staples, Jose Celdran, Mark Hoffman, Michael Hoffman, Clark Heinrich, Jerry Brown, Julie Brown, Jan Irvin, John Rush, Cyberdisciple.

mushroom-imagery deniers (pilzbaum deniers) – Scholars who deny purposeful mushroom imagery in Christian art. Erwin Panofsky, Gordon Wasson, Andy Letcher, Thomas Hatsis, Ronald Huggins.

PMTs = Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists; pilzbaum affirmers. Huggins’ term in his “Foraging Wrong” article, 2024.

PMDs = Psychedelic Mushroom Deniers; my term countering Huggins, describing his own camp in a slightly diminishing, dismissive way.

branching – In the pilzbaum genre of medieval art, branches, such as a tree branching into two mushrooms; a tree with crown supported by Y branches, or crown supported by a group of small branches. Also cut branches; visually cut (occluded) branches; or cut right trunk.

branching theory – Branching and non-branching features ultimately depict by analogy and refer to the branching possibility worldmodel of the ordinary state, vs. the non-branching, frozen, pre-existing worldmodel that’s typically experienced on Psilocybin.

Medieval mushrooms-tree artists were more interested in presenting a message about branching, in conjunction with mushrooms, than presenting a message that’s just about mushrooms.

The artists’ message is:

“Reject branching possibilities (while on mushrooms), to avoid the threat of loss of control, and have stable, viable self-control.”

“On mushrooms, switching to the non-branching worldmodel avoids the threat of loss of control.”

That is my advanced and sophisticated explanation, to turn the apparent “problem” of mushroom-trees having branches, into an advantage, to prove that mushroom-trees purposefully mean mushrooms.

Mushroom-trees purposefully mean mushrooms, as positively evidenced by their branches (and especially cut-branches), conveyed via combining {mushrooms} and {branching} motifs together with {handedness} and {stability} motifs.

See Also

Erwin Panofsky’s Letters to Gordon Wasson, Transcribed

Jerry Brown, Julie Brown (2019). “Entheogens in Christian art: Wasson, Allegro, and the Psychedelic Gospels.” Journal of Psychedelic Studies. 22 pages.

https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2019.019

https://www.academia.edu/40412411/Entheogens_in_Christian_art_Wasson_Allegro_and_the_Psychedelic_Gospels

Keywords: Art History, History of Christianity, Psychedelics, Anthropology of Christianity, Medieval Church History.

Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings (Brinckmann 1906)

Which Two pilzbaum Art Images Did Panofsky Attach in the First Letter to Wasson?

Deniers’ Logical Fallacies in the Pilzbaum (Mushroom-Trees) Debate

Wasson and Allegro on the Tree of Knowledge as Amanita (Egodeath.com) — March 2006 article for the Journal of Higher Criticism.

In simple terms some involved are just plain ordinary world mindset of unawareness no matter how much experience they have.

And no matter what, until the pilzbaum deniers et al have studied the Egodeath Theory in depth, opening their minds into understanding the birth of religion from mystic sltered state religious experience, how can anyone expect them to have the same vision as you have.

Helen Keller was blind and couldn’t relate to the world until she learned one word attached to what she could feel through her bare hands, ‘water,’ and then the entire world opened up for her.

LikeLike