Erwin Panofsky’s 1952 Letters to Gordon Wasson, published by Brown & Brown 2019, transcribed by Michael Hoffman, Egodeath.com, EgodeathTheory.WordPress.com, Feb. 5, 2023.

Contents:

- May 2, 1952 Letter 1 from Panofsky to Wasson

- Photograph of Letter 1

- Citation of Letter 1

- Transcription of Letter 1

- Transcription of Letter 1 Broken Up per Sentence

- Sentence 1.1 (your words about my talk)

- Sentence 1.2 (word of warning)

- Sentence 1.3 (art historian consult: nothing mushrooms)

- Sentence 1.4 (only one example of pilzbaum)

- Sentence 1.5 (pine hundreds instances development)

- Sentence 1.6 (little book by Brinckmann)

- Sentence 1.7 (enclose specimens pine into mushroom)

- Sentence 1.8 (prototypes became unrecognizable)

- Sentence 1.9 (Brinckmann Tree Stylizations)

- May 12, 1952 Letter 2 from Panofsky to Wasson

- Photograph of Letter 2

- Citation of Letter 2

- Transcription of Letter 2

- Transcription of Letter 2 Broken Up per Sentence

- Sentence 2.1 (thanks for reply to 1st letter)

- Sentence 2.2 (induce ecstasy by Amanita)

- Sentence 2.3 (French witches)

- Sentence 2.4 (pilzbaum so universal in so many representations)

- Sentence 2.5 (ignorant misunderstood prototype as mushroom)

- Sentence 2.6 (would have omitted branches)

- Sentence 2.7 (religious art little reason to think of mushrooms)

- Sentence 2.8 (not occur in Bible or Saints)

- Sentence 2.9 (keep pictures)

- Sentence 2.10 (recommend Brinckmann)

May 2, 1952 Letter 1 from Panofsky to Wasson

Photograph of Letter 1

Published by Jerry B. Brown & Julie M. Brown 2019: https://www.academia.edu/40412411/Entheogens_in_Christian_art_Wasson_Allegro_and_the_Psychedelic_Gospels

Citation of Letter 1

Letter of Erwin Panofsky to R. Gordon Wasson, May 2, 1952. Wasson Archives, Harvard University Herbarium, Cambridge, Mass. Tina and R. Gordon Wasson Ethnomycological Collection Archives, ecb00001, series IV, drawer W3.2, folder 20. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

First published by Jerry Brown & Julie Brown (2019). Entheogens in Christian art: Wasson, Allegro, and the Psychedelic Gospels. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, Volume 3: Issue 2, pp. 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2019.019 – https://www.academia.edu/40412411/Entheogens_in_Christian_art_Wasson_Allegro_and_the_Psychedelic_Gospels.

Transcription of Letter 1

Transcribed by Michael Hoffman, Egodeath.com, EgodeathTheory.WordPress.com, February 5, 2023.

THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL STUDIES

May 2, 1952

Mr. R. Gordon Wasson,

J.P.Morgan & Co.,

23 Wall Street,

New York 8, N.Y.

Dear Mr. Wasson:

Many thanks for your kind words about my little talk and the photostat of the discussion centered around the fresco of Plaincourault. Please let me put in a word of warning. In my opinion — which, I am confident, will be shared by any art historian you may care to consult — the plant in this fresco has nothing whatever to do with mushrooms (which would indeed be surprising since it was the tree, and not the mushroom, of good and evil which brought about the transgression of the First Parents), and the similarity with Amanita muscaria is purely fortuitous.

The Plaincourault fresco is only one example — and, since the style is very provincial, a particularly deceptive one — of a conventionalized tree type, prevalent in Romanesque and Early Gothic art, which art historians actually refer to as “mushroom tree” or, in German writing, Pilzbaum. It comes about by the gradual schematization of the impressionistically rendered Italian pine tree in Roman and Early Christian painting, and there are hundreds of instances exemplifying this development – unknown, of course, to mycologists. If you are interested, I recommend a little book by A. E. Brinckmann, Die Baumdarstellung im Mittelalter (or something like it), where the process is described in detail. Just to show what I mean, I enclose two specimens: a miniature of ca. 990 which shows the inception of the process, viz., the gradual hardening of the pine into a mushroom-like shape, and a glass painting of the thirteenth century, that is to say about a century later than your fresco, which shows an even more emphatic schematization of the mushroom-like crown. What the mycologists have overlooked is that the mediaeval artists hardly ever worked from nature but from classical prototypes which in the course of repeated copying became quite unrecognizable.

With best regards,

Sincerely, Erwin Panofsky

[handwritten]

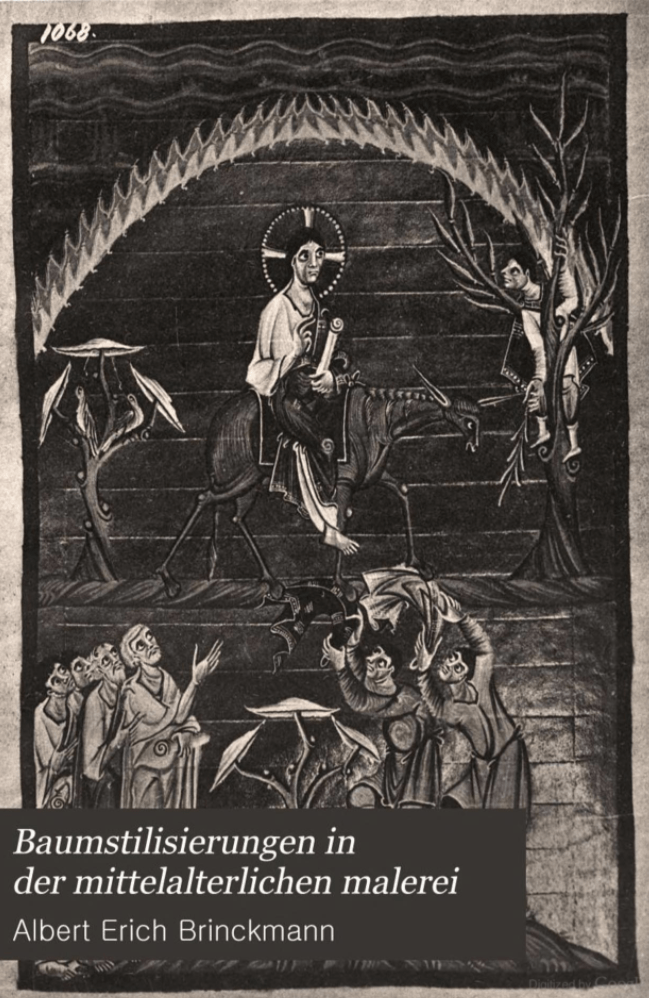

Albert Erich Brinckmann

Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen malerei

/ end of transcription of letter 1 from Panofsky 1952, published by Jerry B. Brown & Julie M. Brown 2019

Typewriter typo fixes:

- Omitted extra space next to punctuation.

- Fixed typo “misuderstood”.

- Corrected “by surprising” to “be surprising”.

The partial transcription of letter 1 in Wasson’s 1968 book Soma differs from the photograph in slight details: commas, ‘a’, capitalization of “Early Christian”.

Transcription of Letter 1 Broken Up per Sentence

Letter of Erwin Panofsky to R. Gordon Wasson, May 2, 1952. Wasson Archives, Harvard University Herbarium, Cambridge, Mass. Published by Jerry B. Brown & Julie M. Brown 2019:

https://www.academia.edu/40412411/Entheogens_in_Christian_art_Wasson_Allegro_and_the_Psychedelic_Gospels, transcribed by Michael Hoffman, February 4, 2023, https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com.

THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL STUDIES

May 2, 1952

Mr. R. Gordon Wasson,

J.P.Morgan & Co.,

23 Wall Street,

New York 8, N.Y.

Dear Mr. Wasson:

Sentence 1.1 (your words about my talk)

Many thanks for your kind words about my little talk and the photostat of the discussion centered around the fresco of Plaincourault.

Sentence 1.2 (word of warning)

Please let me put in a word of warning.

Sentence 1.3 (art historian consult: nothing mushrooms)

In my opinion — which, I am confident, will be shared by any art historian you may care to consult — the plant in this fresco has nothing whatever to do with mushrooms (which would indeed be surprising since it was the tree, and not the mushroom, of good and evil which brought about the transgression of the First Parents), and the similarity with Amanita muscaria is purely fortuitous.

Sentence 1.4 (Only one example of Pilzbaum)

The Plaincourault fresco is only one example — and, since the style is very provincial, a particularly deceptive one — of a conventionalized tree type, prevalent in Romanesque and Early Gothic art, which art historians actually refer to as “mushroom tree” or, in German writing, Pilzbaum.

Sentence 1.5 (Pine Hundreds Instances Development)

It comes about by the gradual schematization of the impressionistically rendered Italian pine tree in Roman and Early Christian painting, and there are hundreds of instances exemplifying this development – unknown, of course, to mycologists.

Sentence 1.6 (Little Book by Brinckmann)

If you are interested, I recommend a little book by A. E. Brinckmann, Die Baumdarstellung im Mittelalter (or something like it), where the process is described in detail.

Sentence 1.7 (Enclose Specimens Pine into Mushroom)

Just to show what I mean, I enclose two specimens: a miniature of ca. 990 which shows the inception of the process, viz., the gradual hardening of the pine into a mushroom-like shape, and a glass painting of the thirteenth century, that is to say about a century later than your fresco, which shows an even more emphatic schematization of the mushroom-like crown.

Sentence 1.8 (Prototypes Became Unrecognizable)

What the mycologists have overlooked is that the medieval artists hardly ever worked from nature but from classical prototypes which in the course of repeated copying became quite unrecognizable.

With best regards,

Sincerely, Erwin Panofsky

Sentence 1.9 (Brinckmann Tree Stylizations)

[handwritten:]

Albert Erich Brinckmann

Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen malerei

/ end of transcription of letter 1 from Panofsky 1952, published by Jerry B. Brown & Julie M. Brown 2019

May 12, 1952 Letter 2 from Panofsky to Wasson

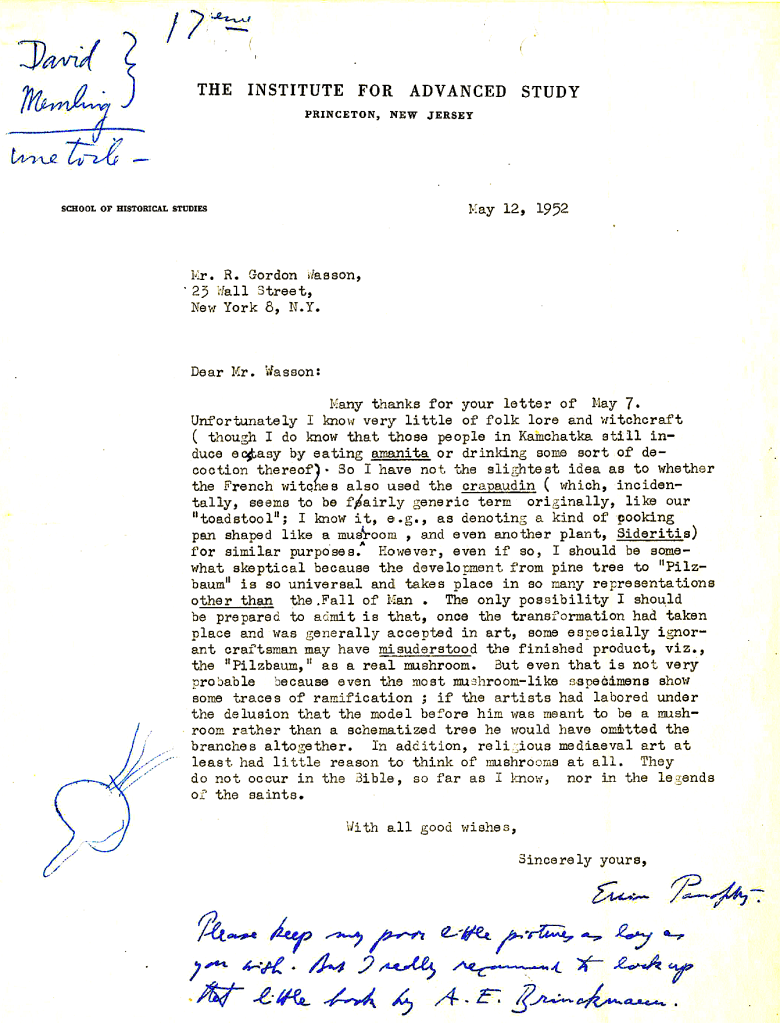

Photograph of Letter 2

https://www.academia.edu/40412411/Entheogens_in_Christian_art_Wasson_Allegro_and_the_Psychedelic_Gospels

Citation of Letter 2

Letter of Erwin Panofsky to R. Gordon Wasson, May 12, 1952. Wasson Archives, Harvard University Herbarium, Cambridge, Mass. Tina and R. Gordon Wasson Ethnomycological Collection Archives, ecb00001, series IV, drawer W3.2, folder 20. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

First published by Jerry Brown & Julie Brown (2019). Entheogens in Christian art: Wasson, Allegro, and the Psychedelic Gospels. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, Volume 3: Issue 2, pp. 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2019.019 – https://www.academia.edu/40412411/Entheogens_in_Christian_art_Wasson_Allegro_and_the_Psychedelic_Gospels.

Transcription of Letter 2

Transcribed by Michael Hoffman, Egodeath.com, EgodeathTheory.WordPress.com, February 5, 2023.

[handwritten upper left:]

David Memling [illegible] 17

THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL STUDIES

May 12, 1952

Mr. R. Gordon Wasson,

23 Wall Street,

New York 8, N.Y.

Dear Mr. Wasson:

Many thanks for your letter of May 7. Unfortunately I know very little of folk lore and witchcraft (though I do know that those people in Kamchatka still induce ecstasy by eating amanita or drinking some sort of decoction thereof). So I have not the slightest idea as to whether the French witches also used the crapaudin (which, incidentally, seems to be fairly generic term originally, like our “toadstool”; I know it, e.g., as denoting a kind of cooking pan shaped like a mushroom, and even another plant, Sideritis) for similar purposes. However, even if so, I should be somewhat skeptical because the development from pine tree to “Pilzbaum” is so universal and takes place in so many representations other than the Fall of Man. The only possibility I should be prepared to admit is that, once the transformation had taken place and was generally accepted in art, some especially ignorant craftsman may have misu[n]derstood the finished product, viz., the “Pilzbaum,” as a real mushroom. But even that is not very probable because even the most mushroom-like specimens show some traces of ramification; if the artists had labored under the delusion that the model before him was meant to be a mushroom rather than a schematized tree he would have omitted the branches altogether. In addition, religious mediaeval art at least had little reason to think of mushrooms at all. They do not occur in the Bible, so far as I know, nor in the legends of the saints.

With all good wishes,

Sincerely yours,

Erwin Panofsky.-

[handwritten]

Please keep my poor little pictures as long as you wish. And I really recommend to look up that little book by A. E. Brinckmann.

/ end of transcription of letter 2 from Panofsky 1952, published by Jerry B. Brown & Julie M. Brown 2019

Adjustments made:

- Changed “to be fairly generic term” to “to be a fairly generic term”

Transcription of Letter 2 Broken Up per Sentence

Letter of Erwin Panofsky to R. Gordon Wasson, May 12, 1952. Wasson Archives, Harvard University Herbarium, Cambridge, Mass. Published by Jerry B. Brown & Julie M. Brown 2019:

https://www.academia.edu/40412411/Entheogens_in_Christian_art_Wasson_Allegro_and_the_Psychedelic_Gospels, transcribed by Michael Hoffman, February 4, 2023, https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com.

[handwritten upper left:]

David Memling [illegible] 17

THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL STUDIES

May 12, 1952

Mr. R. Gordon Wasson,

23 Wall Street,

New York 8, N.Y.

Dear Mr. Wasson:

Sentence 2.1 (thanks for reply to 1st letter)

Many thanks for your letter of May 7.

Sentence 2.2 (induce ecstasy by Amanita)

Unfortunately I know very little of folk lore and witchcraft (though I do know that those people in Kamchatka still induce ecstasy by eating amanita or drinking some sort of decoction thereof).

Sentence 2.3 (French witches)

So I have not the slightest idea as to whether the French witches also used the crapaudin (which, incidentally, seems to be fairly generic term originally, like our “toadstool”; I know it, e.g., as denoting a kind of cooking pan shaped like a mushroom, and even another plant, Sideritis) for similar purposes.

Sentence 2.4 (pilzbaum so universal in so many representations)

However, even if so, I should be somewhat skeptical because the development from pine tree to “Pilzbaum” is so universal and takes place in so many representations other than the Fall of Man.

Sentence 2.5 (ignorant misunderstood prototype as mushroom)

The only possibility I should be prepared to admit is that, once the transformation had taken place and was generally accepted in art, some especially ignorant craftsman may have misu[n]derstood the finished product, viz., the “Pilzbaum,” as a real mushroom.

Sentence 2.6 (would Have omitted branches)

But even that is not very probable because even the most mushroom-like specimens show some traces of ramification; if the artists had labored under the delusion that the model before him was meant to be a mushroom rather than a schematized tree he would have omitted the branches altogether.

Sentence 2.7 (religious art Little Reason to think of mushrooms)

In addition, religious mediaeval art at least had little reason to think of mushrooms at all.

Sentence 2.8 (not Occur in Bible or Saints)

They do not occur in the Bible, so far as I know, nor in the legends of the saints.

With all good wishes,

Sincerely yours,

Erwin Panofsky.-

Sentence 2.9 (keep pictures)

[handwritten]

Please keep my poor little pictures as long as you wish.

Sentence 2.10 (recommend Brinckmann)

[handwritten]

And I really recommend to look up that little book by A. E. Brinckmann.

/ end of transcription of letter 2 from Panofsky 1952, published by Jerry B. Brown & Julie M. Brown 2019

References

Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings (Brinckmann 1906) – citations include:

Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen Malerei

(Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings)

Albert Erich Brinckmann, 1906

86 pages

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/mode/2up

Letters of Erwin Panofsky to R. Gordon Wasson, May 2 & May 12, 1952. Wasson Archives, Harvard University Herbarium, Cambridge, Mass. Tina and R. Gordon Wasson Ethnomycological Collection Archives, ecb00001, series IV, drawer W3.2, folder 20. Botany Libraries, Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University.

The letters were first published by Jerry Brown & Julie Brown (2019). Entheogens in Christian art: Wasson, Allegro, and the Psychedelic Gospels. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, Volume 3: Issue 2, pp. 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2019.019 – https://www.academia.edu/40412411/Entheogens_in_Christian_art_Wasson_Allegro_and_the_Psychedelic_Gospels

Dear Michael,

While we realized the importance of publishing the two Panofsky letters to Wasson side-by-side, you have obviously grasped and illuminated their greater importance in the entire Mushrooms in Christian Art debate. In our opinion, there is no debate.

Due to the focus and interpretation you’ve brought to these letters, we consider their discovery at the Wasson Archives and our subsequent publication to be one of our most significant discoveries – along with the documentation of Wasson’s meetings with the Pope during his time at JP Morgan which handled Vatican accounts and, of course, the extensive images of both Amanita muscaria and psilocybin images in Christian art published in The Psychedelic Gospels.

Thanks for acknowledging our work in your post,

Julie and Jerry Brown

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mystery intrigue from a novel by Brown, Brown, & Brown:

How did Huggins’ Foraging Wrong 2024 article find out about the two Panofsky letters in drawer such-and-so, if not from Brown 2019, and why does it cite only Brown 2016, not 2019?

Huggins wrote about how we actually cannot “consult” art historians’ publications about pilzbaum, because these competent art historians who are so thoroughly familiar with pilzbaum have never published anything on the topic, which is of mere peripheral importance:

“Trees, being peripheral to the more central features of medieval iconography, are not often discussed by art historians.

“A noted[!] exception is Albert Erich Brinckmann’s Baumstilisierungen in der mittelalterlichen Malerei (1906), a work recommended by Panofsky in his letters to Wasson back in 1952.”

AS IF scholars and mycologists have had access to Panofsky’s letters (both citing Brinckmann) since 1952 or 1968!

AS IF we (Brown) didn’t just find the Brinckmann citation and recognize its importance only recently, in 2019!

And how does Huggins expect anyone to use his useless, unhelpful citation of drawer such-and-so at Harvard?

Wasson and Huggins both use improper, abnormal dancing-about, instead of normal scholarly publications and citations that are usable by scholars.

Did Wasson read the publications of “competent” art historians, per normal scholarship?

No; Huggins promotes instead of library research:

“Wasson readily sought help from people with expertise in fields related to his research.”

“Sought help” from “experts” who never wrote and published on the topic of pilzbaum, and consider trees merely peripheral, not central in importance, and not worth bothering to write and publish about.

___

Huggins tries to excuse Wasson’s obstructionism:

“Given Wasson’s importance the PMTs are generally aware of Panofsky’s warning, and of Wasson’s subsequent remark that “mycologists would have done well to consult art historians.”

“But they reject it as “an unreflective dismissal [that] misses the point,” or a case of Wasson’s being taken in by the “monodisciplinary blindness and interpretive slothfulness of professional researchers,” meaning Panofsky and the other unnamed art historians Wasson consulted.

“One prominent PMT, J.R. Irvin, even complained that “Wasson adopted Panofsky’s interpretation and thenceforth began to force it upon other scholars.

“Uncritical acceptance of the Wasson-Panofsky view lasted, unchecked, for nearly fifty years.” [Irvin, THM]

“It might be noted, however, that many of the works in which the PMTs express contrary views were published during the fifty years to which Irvin refers.”

___

PMTs = Psychedelic Mushroom Theorists; pilzbaum affirmers.

Where are the expert art historian’s works in Huggins’ Bibliography, that discuss the question of pilzbaum relevant to the Wasson-Panofsky view?

There aren’t any (or, as I wrote in my 2006 Wasson article, we can conclude that such writings by art historians are pathetically few and weak); as Huggins admits:

“Trees, being peripheral … are not often discussed by art historians. A noted [read: censored] exception is Brinckmann…”

These “many works” are from pilzbaum affirmers, not from pilzbaum deniers (art historians) regarding the pilzbaum question, whose studies on this topic are nonexistent.

Even Brinckmann’s “little book” from 1906 (that’s all you got?!) is missing from Huggins’ Bibliography section.

In 1996-1998, Samorini finally followed what little of Panofsky’s lead – hundreds of pilzbaum – that Wasson in Soma let leak through.

Huggins continues:

“The only real advantage Wasson has enjoyed was perhaps the result of his [formerly] trusted reputation, based partly on his willingness to engage scholars in other fields as a way of cross-checking his own work, a feature not often encountered in the more generally insular PMTs.”

Normal scholarship uses writing and publication and citation as a way of doing the above.

Why require this special approach of “reach out and consult competent authorities to measure their speed and strength of disavowal”, for the special, exceptional topic of pilzbaum, only?

“In the meantime, the few art historians with expertise in Ottonian and Romanesque art who are aware of the PMTs claims continue to echo Panofsky.

“When questioned on the topic by the writer, prominent art historian Elina Gertsman responded crisply [⏱]:

“I very much do not think that Ottonian or Romanesque imagery was in any shape or form influenced by psychedelic mushrooms.””

Argument from crispness?

Huggins does not attempt to present any argumentation provided by this authority.

From this learned, grand, prominent, expert authority on “related topics” that are related to this “peripheral” topic of pilzbaum, we’re only given a name and credentials, along with speed and strength of professed disavowal. Scholarship!

___

The Hoffman Uncertainty Principle:

The more directly you probe and interrogate publicly the competent art authority (who has published nothing on the pilzbaum question), the quicker (and crisper!) the celerity of disavowal.

Huggins presents a bizzarre special-case approach to this topic, only:

Consult the drawer at Harvard.

Consult your local top expert art authority, stopwatch in hand, to measure the celerity with which they disavow pilzbaum.

Every competent art authority: No, no, no, no, there’s no way any credible authority affirms these pilzbaum, no way, no how; we disavow!”

Argument by celerity of authorities’ disavowals.

There is a consistent pattern of withholding and preventing people from seeing the letters.

Huggins is of no help here: he does not publish the letters for scholars to share, and he does not point to the Brown 2019 article or my original transcription page at this site.

Mystery intrigue in the Bibliography of Foraging Wrong:

“Consult” the competent art authorities — yet Huggins’ Bibliography lacks these key entries centrally relevant to main topics discussed in the article body:

Baloney indirection and roundabout dancing:

Huggins wrote:

“The authors venture their claims without an adequate grasp of the standard way of depicting trees and other plants in the art of the period.”

pilzbaum affirmers are extremely grasping of the standard way of depicting trees and other plants in the art of the period:

Every pilzbaum affirmer is intensely aware that art historians describe these trees as “look like mushrooms”, thus their term, the art historians’ term, “pilzbaum“, by which the art historians mean:

The set of trees that look like mushrooms, typifying the genre of medieval art.

The principle of artist responsibility (against Panofsky):

If the artist didn’t want art historians to think of mushrooms when seeing these trees, then the artist should not have made their trees look so distinctly like mushrooms.

Just like with every other item depicted, as art historians say on every other topic – artists were free within the genre.

Within this special topic, only, Panofsky robs artists of their freedom and forces them to follow “prototypes”, trying to remove artists’ responsibility for making viewers think of mushrooms.

The special pleading fallacy.

“Nor have they been much inclined to consult art historians, whose opinions on such matters they show little interest in.

“This began when PMTs responded negatively to the advice art historian Erwin Panofsky gave to New York banker and amateur mycologist G. Gordon Wasson in 1952.”

Huggins nicely leaves out the fact that Wasson only allowed (for 51 years, 1968-2019) only half of the first of the two Panosfky letters to be seen by everyone.

So much for emphatically pressuring mycologists or pilzbaum affirmers to “consult” art historians:

Wasson and Huggins are all talk, posturing, and bluff, while withholding useful citations for critical scholarship – citations that support, not refute, pilzbaum affirmers.

Art authorities have no credibility until they publish something on the unimportant, “peripheral” topic of pilzbaum.

As the official voice, spokesman, and apologist for the Gordon Wasson 1968 and Erwin Panofsky 1952 argument (in both letters in full), Ronald Huggins is answerable for Wasson’s censorship of:

Art historians have earned their disrespect, and have some answering to do.

Huggins repeats the Panofsky argument: the items that art historians describe as pilzbaum don’t look like mushrooms, because they have branches. Huggins, repeating Panofsky’s newly available argument, tries to dismiss pilzbaum because they “have branches”.

The “branches” themselves typically look like literal mushrooms. The “branches” that Huggins (following Panofsky) uses to dismiss the mushroom interpretation look like mushrooms.

If pilzbaum don’t look like mushrooms, why do art historians themselves describe them as pilzbaum, mushroom trees?

Art historians don’t take the topic of pilzbaum or trees seriously enough to write and publish anything on the topic, and yet Huggins expects pilzbaum affirmers to take the “prominent”, “competent” authorities who published on “related topics” seriously.

Huggins expects art historians to be taken seriously on this specific topic. Why?

Respect needs to be earned and warranted, but what we’re given instead is censorship and withholding citations and art evidence.

There is every reason to not take pilzbaum deniers seriously.

LikeLike