Michael Hoffman

Jan. 3, 2025

Contents:

- Motivation of this Page

- The Concerns of the Egodeath Theory and Mushroom-Tree Esotericists

- During Psilocybin Transformation, Does Viable Stable Control Result from Possibilism-Thinking, or from Eternalism-Thinking?

- Irrelevant: “Free Will vs. Determinism”; Closer: “Presentism vs. Eternalism”; On-Target: “Possibilism vs. Eternalism”

- Standing in Switch Stance 🛹 – Practicing {stand on right foot} Relying on 2-Level, Dependent Control

- See Also

- Video: 4 Hours of World’s TOP SCIENTISTS on FREE WILL

- Transcript of Entire Video

- Introduction by Curt Jaimungal

- Michael Levin

- David Wolpert (Part 1)

- Donald Hoffman, Joscha Bach

- Joscha Bach, Control Systems (1)

- Stuart Hameroff

- Claudia Passos

- Wolfgang Smith

- Enlightenment (Realize Eternalism) vs. Salvation (Transcend Eternalism)

- Bernardo Kastrup

- Matt O’Dowd

- Anand Vaidya

- Chris Langan, Bernardo Kastrup

- David Wolpert (Part 2)

- Scott Aaronson

- Nicolas Gisin

- David Wolpert (Part 3)

- Motte and Bailey Fallacy

- Brian Keating, Lee Cronin

- Joscha Bach, Control Systems (2)

- Karl Friston

- Noam Chomsky (Part 1)

- John Vervaeke, Joscha Bach (Control Systems)

- Stephen Wolfram

- BOTTOM OF TRANSCRIPT, CLEANED UP EARLIER TODAY, MOVED FROM IDEA DEVELOPMENT PAGE 27 – 3:21:00 – lots of my commentary below

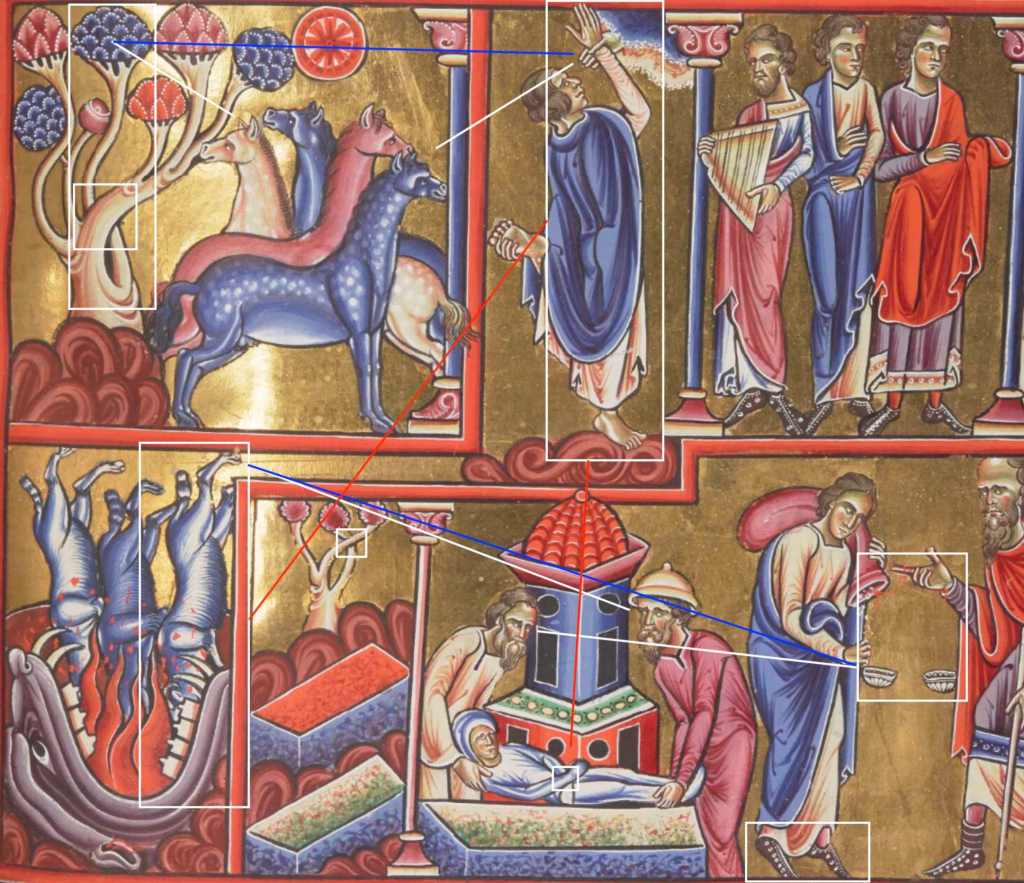

- The medieval art genre of {mushroom-trees} is concerned with stable control in the psychedelic state: that is the test of truth, relevance, concern; the standard of reference

- Jonathan Blow

- 🏋️♂️📚

- Noam Chomsky (Part 2)

- The Relevant, Psilocybin-Transformation Concern, as the Reference Point: Does Viable Stable Control Result from Possibilism-Thinking, or from Eternalism-Thinking?

- In What Sense Do People Make Decisions?

- People Who Properly Disbelieve Freewill Detectably Behave Differently

- Thomas Campbell

- John Vervaeke

- Astral Ascent Mysticism: Prime Mover Sphere Drives Sphere of the fixed stars; Eternalism

- From {king steering in tree} through {mixed wine at banquet} to {snake frozen in rock}

- The Mytheme Theory (part of the Egodeath Theory) Provides and Explains Suitable Analogies

- James Robert Brown: The Platonistic Perspective on Free Will

- Anil Seth: Strange Loops

- Douglas Hofstadter

- More ontoprisms coming…

- Video: Free Will, Morality, Self Awareness | Robert Sapolsky

Motivation of this Page

Video:

4 Hours of World’s TOP SCIENTISTS on FREE WILL

YouTube Channel: Curt Jaimungal

Nov 28, 2023

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SSbUCEleJhg —

“In our first ontoprism, we take a look back at FREE WILL across the years at Theories of Everything.

4 Hours of No-free-will Imprisonment Enslavement then Spiritual Redemption

A few sections warrant my inspection. Certainly there are some valuable relevant ideas in this long video. Hard to assess without the present page.

I already cleaned up the bottom part of the transcript in idea development page 27.

Here’s the entire transcript, including that, b/c easiest for me to process all at once.

The Concerns of the Egodeath Theory and Mushroom-Tree Esotericists

The Relevant, Psilocybin-Transformation Concern, as the Reference Point:

During Psilocybin Transformation, Does Viable Stable Control Result from Possibilism-Thinking, or from Eternalism-Thinking?

When the Egodeath theory and Psilocybin form the field & approach of Loose Cognitive Science, the free will vs. determinism analysis will change a lot, including eternalism opening up to be revealed as relevant, instead of domino-chain determinism.

The debate will switch away from “free will vs. determinism” and also away from the newer off-target contrast, “presentism vs. eternalism”, to the relevant debate, possibilism vs. eternalism.

Irrelevant: “Free Will vs. Determinism”; Closer: “Presentism vs. Eternalism”; On-Target: “Possibilism vs. Eternalism”

I wrote a lot about placing randomness into block-universe eternalism, in:

Self-control Cybernetics, Dissociative Cognition, & Mystic Ego Death (1997 core theory spec) (Hoffman, 1997) https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2020/11/30/self-control-cybernetics-dissociative-cognition-mystic-ego-death/

The first posts in Egodeath Yahoo Group 2001 contrast essentially,

- branching Quantum Mysticism

- non-branching 4D Spacetime Mysticism

Many points in this video are suggestive about explaining how the medieval art genre of {mushroom-trees} works, what concerns it depicts and emphasizes, and how I can describe differently the concerns of Egodeath theory.

Mushroom-tree artists are NOT in a Phil-vs.-Physics Dept. armchair debate about quantum flapdoodle theorizing.

Esoteric esotericism & the Egodeath theory IS NOT CONVENTIONAL DEBATE about “FREE WILL VS. DETERMINISM”.

NOR DEBATE about “POSSIBILISM VS ETERNALISM”. Rather:

In what sense is possibilism is the case, as reflected in the intense mystic altered state?

In what sense is eternalism the case?

What does it mean to functionally practically and effectively integrate these, integrated possibilism/eternalism thinking, per maturity as defined by the Teacher of Truth, Psilocybin?

Standing in Switch Stance 🛹 – Practicing {stand on right foot} Relying on 2-Level, Dependent Control

https://www.google.com/search?q=switch+stance+skateboarding

Balancing on a skateboard, a person has an innate strong preference for either L foot forward or R foot forward.

Skateboarding switch stance is hard, a deliberately learned skill – unless one has committed to ambidextrous from the start.

Switch stance requires hard work and uphill-battle re-learning the non-natural stance.

We all stand in Regular stance, weight on L foot.

We all have to work hard to learn to stand in Goofy stance, like the Goofy cartoon character surfing in an animation: weight on R foot; R foot forward on skateboard.

Then we have stable control in the Psilocybin state. This is the message of the mushroom-tree artists.

March 4, 2023

See Also

The “All At Once” Universe Shatters Our View of Time (Emily Adlam)

Excellent video interview & transcript, highly relevant to Egodeath theory of psychedelic eternalism:

The “All At Once” Universe Shatters Our View of Time (Emily Adlam)

Video: 4 Hours of World’s TOP SCIENTISTS on FREE WILL

Video:

4 Hours of World’s TOP SCIENTISTS on FREE WILL

YouTube Channel: Curt Jaimungal

Nov 28, 2023

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SSbUCEleJhg —

“In our first ontoprism, we take a look back at FREE WILL across the years at Theories of Everything.

“If you have suggestions for future ontoprism topics, then comment below.”

Transcript of Entire Video

Introduction by Curt Jaimungal

00:00:00 Introduction

Free will is a representation within the system that it’s made a decision and the decision is being made on the best understanding of what’s correct.

The dynamics that break up that undifferentiated ocean of potential selves into one, two or three or more, it can go different ways.

Out of this like ocean of potentiality, these cells, you know, 50,000 cells, and each of them will have specific goals.

Objectivists say that these probabilities are pointing to some real thing in the world.

There is some real random generator in the world.

And subjectivists say, no, these are just degrees of belief.

What is free will?

How is it different than agency?

What constitutes a willful and an unwillful action?

How do you define yourself as separate from the world in order for you to even say that you act on the environment?

What does physics have to say about all of this?

And what are some of the alternatives to the classic compatibilism versus libertarian notions of free will?

Perhaps our question is explored today by the approximately 25 or so guests of Theories of Everything.

For those of you who are new to this channel, my name is Curt Jaimungal, and what we usually do is explore theories of everything in the physics sense from a mathematical perspective.

However, this is also a philosophical channel, investigating the fundamental laws, whatever they may be.

You can think of it as an analysis from multiple perspectives on the largest looming questions we have, while also exploring an experiential approach.

We’ve been having issues monetizing the channel with sponsorship, so if you’d like to contribute to the continuation of Theories of Everything, then you can donate through PayPal, Patreon, or through cryptocurrency.

Your support goes a long way in ensuring the longevity and quality of this channel.

Thank you.

Links are in the description.

What you’re about to watch is a new format called an Onto Prism, where instead of having comprehensive interviews with a single guest on a variety of subjects, we’re flipping that and diving into a singular topic with a variety of guests.

Think of it like a buffet where there’s a smorgasbord of variegated ideas, and you can sample and choose the one you like best, or create your own Weltanschauung by sampling from the assortment.

Hearing opinions on a specific theme is strewn across the over 100 podcasts over the past three years on the Theories of Everything channel, though for convenience, they’re co-located here.

The guests in this episode include Michael Levin, Carl Friston, David Walpart, Donald Hoffman, Joscha Bach, Stuart Hameroff, Wolfgang Smith, Bernardo Kastrup, Matt O’Dowd from PBS Spacetime, Chris Langan, Nicholas Gissen, Brian Keating, Noam Chomsky, Stephen Wolfram, Jonathan Blow, Thomas Campbell, John Vervaeke, James Robert Brown, Anil Sith, and Claudia Paisos.

There’s also Anand Vaidya and Scott Aronson.

This Onto Prism on free will is in preparation for a mountainous interview with the legendary Robert Sapolsky on this very issue. [section at bottom of this page]

If you enjoy this format, then you can suggest other topics for future episodes in the comments section.

Now enjoy this peregrination into free will.

Well, again, what I’d actually like to do is back up a little bit and put some of what you just said into very simple active inference language.

Michael Levin

00:02:58 Michael Levin

If I see something happening on my Markov blanket, on my interface with the world, then I always have the question, did I do that or did the world do that?

Where the world means everything outside me.

And in a sense, the answer is always the world did it.

So the question becomes, did the world do that in response to something I did to it or did it just do it?

Not in consequence of any of my actions.

And so one gets immediately to this kind of babbling scenario that we’ve talked about many times, in which an infant or a robot or some system is trying to figure out by measuring correlations whether the world’s inputs to it have anything to do with its inputs to the world.

And just asking that question requires enormous representative capacity, because one has to represent one’s actions and represent them pretty well in time.

And one has to have a good memory to represent enough actions to get any kind of statistical support for drawing an inference about correlation.

And that memory has to be represented as a memory, not just part of one’s occurrent input.

So I think this question that you posed is really the key question faced by any agent at all that’s trying to get a model off the ground, which in a sense gets back to the question that Mike asked early, early on about how does this all start?

Maybe it starts with babbling in very simple systems.

You know, I was thinking recently, this whole issue of how many agents are there and where is the border between the agent and the world and how do you self-model that border is a fascinating topic.

And there’s an amazing developmental model for this, which is that, you know, we often talk about one embryo and the embryo does this and the embryo does that.

But actually, what happens at the beginning, let’s say, for example, in amniote embryos is that there’s a flat blastodisc, which has just a few cell layers thick.

So it’s kind of, think of it like a Frisbee and it just has a few cell layers.

And normally what has to happen is that one point in this disc breaks symmetry and then organizes the primary axis of the first embryo and basically tells all the other cells, don’t do it because I’m doing it.

And that’s how you end up with one embryo.

Now that process is very easily perturbed and many people have done it.

I used to do it in my graduate work and what you can do is if you perturb that process, that initial blastodisc, that undifferentiated sort of pool of cells, which are these sort of proto, low-level proto agents, that pool can break up into not one embryo, but actually multiple.

And so you can have, so I did this in bird embryos and you can have twins and chicken and duck and things like this.

You can have in humans, humans have exactly the same structure.

You can get them head to head.

You can get them side by side.

You can get all sorts of geometries.

You can get triplets.

You can get multiple individuals emerging by different partitions of this really kind of medium, this particulate medium where you have a bunch of cells and you don’t know ahead of time how many individuals at the level, how many larger individuals, so embryos, are going to arise from this medium because the dynamics by which, and that’s local activation and long range inhibition and things like that, the dynamics that break up that undifferentiated ocean of potential cells into one, two, or three or more cells is actually, it’s very dynamic.

It can go different ways.

And then you get interesting things like this.

So for example, you might know that human conjoined twins that are sort of stuck together side to side, one of the twins often has left, right asymmetry defects.

And it’s because when you have two twins side by side, the cells in the middle, both twins can’t quite agree on who they belong to.

Are they the right side of this twin or are they the left side of that twin?

And both twins think they belong to them, but in fact, they’re overlapping, they’re the same cells.

And so one side will have correct left and right, the other side will have like two rights, for example.

This ends up giving one of the twins laterality defects with respect to hardened gut pattern.

And so their models, each twins, as the collective of cells tries to compute things like where things are and what’s left and what’s right and so on, their models can disagree with each other.

They can draw the boundary between self and world in different ways, and you can have these sort of disputes over certain areas as to who they actually belong to.

And so I’m just incredibly interested in this process of individualization, so to speak, out of this like ocean of potentiality, these cells, you know, 50,000 cells and some number of individuals at the embryo level will be formed.

And each of them will have specific goals and morphospace, each of them will try to achieve very specific morphologies.

And you don’t know ahead of time how many there were going to be.

All right, we’ve just been diving into the interplay between the self and the world with Michael Levin, Carl Fristin, and Chris Field.

Again, every link is in the description.

David Wolpert (Part 1)

00:08:51 David Wolpert (Part 1)

They dissect the process of self-modeling and individualization, which lead us naturally to our next guest, David Wohlpart, who challenges us with a monotheistic perspective on freewill.

If they both have free will, at least once.

That’s incredibly interesting.

So it’s an impossibility result against more than one God?

Yes.

Yep.

That’s why it’s called the monotheism theorem.

It might be that we are in a universe in which you could have one God, who knows?

I’m not going to go there.

I mean, my personal feeling—conclusions on it are that in our particular universe, no.

But there is no reason why—I think the concept itself is not inherently self-contradictory like Riposte’s demon.

There could be universes.

I would say there’s no sense in which we can actually rule them out, in fact, in which there are deities.

But there cannot be any of them that support two deities.

So we might be in one of those ones in which there is a deity, who knows?

But we can’t be in one in which there’s more than one.

And when you say deity, there can’t be two omniscient deities?

There can’t be two that have free will.

So you could have one where there’s Zeus and Hera, but Zeus can always be in a particular state that restricts Hera from being in some of her particular states.

In that sense, she does not have free will of him.

At one particular time, one particular state of Zeus, it’s just not going to be any possible storyline in any of the universe, in our universe, in which Hera is in one of her particular states.

There’s some limitation.

My being in one particular state at one particular time, it could cause a restriction on the possible states that you could be in at that time.

And if that’s true, then we have no free will.

Have you heard of Norton’s Dome?

Norton’s Dome.

I think I did a while ago, ringing a bell, but I can’t bring it up.

Sure.

It’s an experiment about Newtonian mechanics, and it’s to show that Newtonian mechanics isn’t deterministic, even though it’s often said it is.

And the reason is there are certain configurations you can set up such that there’s not a unique answer to the differential equations.

You know, ordinarily in physics, just for people to know, one of the reasons why mathematicians quibble with physicists is that physicists hand wave and gloss over many details.

And so one of them is whenever we have an ordinary differential equation, we tend to say there’s uniqueness in existence.

However, that’s contingent on something called the Lipschitz continuity.

And if you don’t have Lipschitz continuity, you don’t necessarily have a unique solution.

So you basically set up a certain situation with a ball on a dome, and the equation for the dome is fairly simple.

It’s almost like a parabola.

And then it turns out one solution is it stays there forever, zero velocity initially.

And then another solution is at some point t, and the time t is not specified, it goes down some route, and any one of them.

So that’s extremely interesting.

Let’s imagine we live in a Newtonian world.

Is that related to free will, would you say?

Or is that not related to free will?

That’s something different.

I know free will, forget about the sense of intention, interacting with the laws of nature to produce that effect.

Carlos.

Yeah, the Norton’s dome, it’s also, I think it was actually Sabine, who has one of her FQXi essays that she points out that chaos is, in some sense, it can be a much stronger phenomenon that people understand, and that you can set up physical systems in which the chaos is to such a degree that actually passed a certain point in time, you cannot, it is not defined, but the state of the system will be after that.

So that’s, I think that’s the context in which I ran across it.

It’s also, there are related things, the work that goes back to two people called Porel and Richards.

Those were physicists who is well known that, for example, the three body problem, where even if you do, so there you do have the standard Lipschitz continuity, and so on, you’ve got gravitational attraction, and so on.

You can set it up to be a, what’s called a universal Turing machine.

You basically, what you do is you encode the input tape to that Turing machine into the actual precise initial conditions of these three bodies.

And then by reading the appropriate bits of the state of the system at some future time, you can figure out what that universal Turing machine state of its tape would be at that time.

What this means is that you can feed in a configuration that’s actually the halting problem so that that physical system, in fact, it violates the Church-Turing thesis, that physical system, its state in the future would not be complete.

Donald Hoffman, Joscha Bach

00:13:48 Donald Hoffman, Joscha Bach

All right, now having just gone through the monotheistic lens with David Walpart, we’re pivoting to Donald Hoffman’s cognitive neuroscientific perspective.

Also Joscha Bach joins Donald Hoffman.

In a physicalist framework, which I’m, so now I’ll just talk about what most of my cognitive neuroscience peers think, right?

Most of them assume that physical systems are fundamental.

Neural activity causes all of our behavior, and in that case, there can be a fiction of, a useful fiction of free will, but it’s really just going to be a useful fiction.

If I do something, it’s really my neurons with the neural activity that did it, and there is a sense in which you can say, I chose to do it because actually neurons are part of me, so I think that’s the point of view that Dan Dennett takes, for example, on this.

And Sam Harris replies on that, he says, well, yeah, I also grow my fingernails.

I’m not sure that I’m doing that by free will, but I, so it’s not real clear that just because my neurons are doing it, I have free will, just in the same sense that I’m not using free will to grow my fingernails.

So Sam would say there’s no such thing as free will, if you’re a physicalist.

Dan Dennett would say I’m a physicalist, and there is this important notion of free will.

I think that, of course, space-time isn’t fundamental, and so that we have to completely think outside of that box altogether.

And as scientists, we have to say upfront what our hypotheses, what our axioms or fundamental assumptions are, and be very clear about them upfront.

These conscious agents in the mathematics, they get certain inputs, we call them experiences that they have, and then there’s something called a Markovian kernel that describes what actions they take, and those actions affect the experiences of other conscious agents.

So then there’s, so that’s just the mathematics that my team has written down, it’s a very simple notion of a Markovian dynamics of conscious agents interacting.

And it’s not in a physicalist framework, we’re assuming that this is in its own world, right?

These are conscious agents, and that’s the foundation.

Space and time are not the foundation, conscious agents, so conscious experiences and interactions of conscious agents are the foundational notion.

And so then the question is, how shall we understand the probabilities?

So if I get a particular experience that comes into a conscious agent, and it then probabilistically affects the experience of other agents, how shall I understand that probability?

Shall I understand it as a free will choice, or what?

And I could say, I refuse to answer the question, there’s a probability there, and that’s as far as I go with a theory, there’s this agent, so I leave that probability as just where my theory stops, where I say, in some sense, wherever we see a probability in a theory, that’s where explanation stops, right?

That’s basically saying, I don’t know.

So whenever, so I always say this, whenever in a scientific theory you see probabilities coming up, you’re seeing the theory say, this is where I halt, this is where my explanation stops.

And there are two major approaches toward understanding those probabilities, the objectivist and subjectivist to probabilities, right?

So objectivists say that these probabilities are pointing to some real thing in the world.

There is some real random generator in the world.

And subjectivists say, no, these are just degrees of belief.

Whenever you see probabilities, you’re only talking about degrees of belief.

But in either case, explanation stops, right?

How do I come to that belief?

Well, I can only tell you probabilities.

What is that random objective process?

I don’t know, but I can just tell you probabilities.

And so really, whenever you see probabilities in a scientific theory, and they’re all over the place, I read that as saying, here’s where explanation stops and our theories halt.

And if we want to go further, we’re going to have to unpack that probability into some deeper theory.

So if I say that it’s free will in the case of the conscious agents, then, I mean, in some sense, that’s just words.

What theory has is the probabilities, and it has no further explanation.

So if I call that probability a free will, then I can call it that, but I haven’t really done much to give much insight into the notion of free will.

Free will then becomes a primitive, and maybe that’s what I want to do.

I want to say, this is where explanation stops, and so free will is primitive.

So these probabilities are free will, and I agree that that’s where my theory stops, that I can do no further.

Now what’s interesting in the conscious agent dynamics that we’re working on is that any group of conscious agents together also satisfy the definition of a conscious agent, and so they are a conscious agent.

So any conscious agents interacting are also conscious agents.

So in the theory, there’s one conscious agent, because if you take all of them together, they form one conscious agent, but then there are as many, if you’re computational, there’s only a countable number of them, or in my case, I don’t know, it may be an uncountable number of conscious agents.

But what’s interesting is that you unpack this probability in the Markovian kernel.

There could be one big probability for one agent, but you can unpack that into all these dynamical systems that are interacting conscious agents with their own probabilities and their own kernels.

And what’s interesting is that you could then give, in some sense, an unpacking of the notion of free will in that way.

You could say, well, yeah, the one agent has free will and this probability, but I can actually do some non-trivial unpacking of that notion in this sort of recursive unwinding of those probabilities throughout the network.

So there is the possibility here of, I mean, ultimately, there will be a primitive notion of free will that is just primitive and not explained, but given that one, I can explain all these other free wills sort of interacting, arising from this most primitive notion of free will in a non-trivial way.

But once again, I would point out something that I see all the time in scientific theories.

No theory in science will ever explain everything.

And I would love to see if Josje agrees or disagrees.

I will just state to make a strong claim.

There cannot be a theory of everything because every theory has to make assumptions and those assumptions are not explained, they’re assumed.

It’s just that simple.

Okay, am I correct in my summary of your views on free will that if in a physical theory you have probability, now some of that probability is just due to our ignorance, but if there’s a fundamental probability, you can just say, well, that’s indicating that the theories break down, we just don’t know.

Or you can say that there’s something underneath producing those and that which is underneath the probabilities is what you’re calling free will.

Is that correct or is that off?

Right.

So, if I’m a physicalist, I’ll say that that probability is due to some process that I can say no more about, but there’s some process that generates this stuff.

It’s not free will, it’s just a physical process that I don’t know.

But if I’m taking consciousness to be fundamental, then it’s an interesting move to say that probability can be interpreted as free will.

Now, of course, I’m not explaining anything.

I’m just putting the notion free will, the word free will on it, right?

And free will becomes just a primitive notion as well.

So that’s where my explanation stops and the most unpacking I can do is that recursive unpacking that I mentioned, which is an interesting unpacking, but ultimately there’s this primitive notion of free will that I have nothing further to say about.

But I think that that’s not a problem specific to this theory.

The last thing I was saying was that that’s endemic to all scientific theories.

Every scientific theory will have miracles at its foundation.

By miracles, I mean assumptions that are taken for granted and not explained.

If you explain them, then you’ll have a deeper theory with new assumptions that explain those assumptions, but the new assumptions aren’t explained.

So in this sense, science can never have a theory of everything because science theories always have assumptions and the assumptions are what you don’t explain.

Joshua, I know Donald said quite a few, there are quite a few elements to pick from there.

Joscha Bach, Control Systems (1)

23:50

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SSbUCEleJhg&t=1430s

We are interlocking claims, but let’s address them.

First of all, I don’t know whether there can be one theory of everything because my reasoning is not tight enough to make that proof one way or the other.

So at this point, I have to remain agnostic because I think from where I stand, it seems to be possible that there can be a theory of everything.

And it seems to be possible that there cannot.

From a computationalist perspective, whenever you have a set of observations that is finite, you will be able to construct a computational model that explains how to make such patterns.

So in principle, there can always be a theory of everything that you observed.

That’s something that I cannot, that I don’t see a way around this.

So this seems to be sound to me, and I think that can be formally proven, but it seems to be almost trivial that it’s proven.

So it’s more interesting.

The question is, can you narrow this down to a single one, to one theory of everything?

You will be always stuck with infinitely many theories of everything where most of these theories will be super inelegant and redundant and basically recordings of your observations.

Or will there be one theory that is the most elegant and explains everything neatly and wraps it up?

And of course, if you think about the space of all theories and think of them as things that you can do in a language and in which you can define truth.

And if you realize that the languages in which you can define truth consistently are the computational languages, it turns out that all your models are going to be automata and that you can sort the space of automata by the length of their definitions.

So it also seems that in principle, it should be possible to find the shortest automaton between to every pair of automata that you can construct and can up this.

And now the question is, what’s your search procedure for all the possible automata?

Do you have a search procedure that you can hope that terminates?

And this is not a question of whether it’s mathematically possible, but whether it’s efficient.

So is there an efficient strategy to find a theory of everything that is the shortest one?

And so far, we haven’t found one.

And it relates to what AI is doing in machine learning when it tries to identify what’s going on in the domain.

So in principle, we can always be sure that we could be a brain in a vat and everything is just a nefarious conspiracy that is playing out.

And because we cannot exclude this, we can never be sure that our theory of everything is the best theory that could exist of things.

So that’s obviously the case.

But if we take out this single thing and make the assumption that reality is not a conspiracy, I think then it starts to look a lot brighter.

Let’s get to the notion of free will.

I think that free will is tied into the notion of agency.

And the best explanation of what an agent is that I found so far is that an agent is a control system that is intrinsically combined with its own set point generator.

Control Systems, Cybernetics

A control system is a notion from cybernetics.

It means you have some system like a thermostat that is making a measurement using sensors, for instance, the temperature in the room.

And that has effectors by which it can change the dynamics of the system.

So the effector would be a switch that turns the heating on and off and the system that’s being regulated is the temperature in the room.

And the temperature in the room is disturbed by the environment.

And a simple thermostat will only act on its present measurement and then translate this present measurement using a single parameter into whether it should switch or not.

And depending on choosing that parameter well, you have a more efficient regulation or not.

But if you want to be more efficient, you need to model the environment and the dynamics of the system.

And maybe the dynamics of the sensory system and the actuator itself.

When you can do this, it means that you model the future of the regulation based on past observations.

So if you endow the controller with the ability to make a model of the future and use this control model to fine tune the actions of the controller, it means that a controller now is more than a thermostat.

It’s not going to just optimize the temperature in the room the next frame, but it’s going to optimize the integral of the temperature over a long time span.

So it basically takes a long expectation horizon.

The further it goes, the better probably.

And then it tries to minimize all the temperature deviations from the ideal temperature from the set point over that time span.

And this means that depending on the fidelity and detail of the model of its environment and its interaction with the environment and itself, it’s going to be better and better if it assumes that there are trajectories in the world that are the result of its own decisions.

By turning the temperature on and off at this particular point in time, I’m going to get this and this result, depending on the weather outside, depending on how often people open and close the door to the room at different times of the day, depending on the aging of my sensor or the distance of my sensor to the heating, and depending on whether the window on top of the sensor is currently open or closed and so on.

I get lots and lots more ways to differentiate the event flow in the universe and the path that the universe can take.

And the interactions that I can have with the universe that determine whether somebody will open the window and so on and so on.

So you have all these points where the controller is a very differentiated model of reality, where it’s going to prefer some events of others and is going to assign its own decisions to these trajectories.

And this decision making necessarily happens under conditions of uncertainty, which means the controller will never be completely sure which one is going to be the right decision.

The controller will have to make educated guesses, bets on the future.

And this even includes the models of itself, right?

The better the control system understands itself and the limitations of its modeling ability, the better its models are going to be.

So at some point of complexity, this thing is going to understand its own modeling procedure to improve it and to find gaps in it and so on.

And this also means that when it starts to do this, it is going to discover that there are agents in the world, other controllers that have set points, generators and model the future and make decisions.

For instance, people that might open the window when you make the room too hot and you lose energy because of that.

So maybe not overheat the room and people are in the room.

This means you have to model agency at some point and you will also discover yourself as an agent in the world, as a controller, as a set point generator and the ability to model the future.

And you will discover this before you understand how your own modeling of the future works.

So you also have to make bets on how you work before you understand yourself.

So you will discover a self-model.

The self-model is the agent where the contents of your own model are driving the behavior of that agent.

And it’s a very particular agent.

It’s one where your reasoning and your modeling has an influence on what this agent is going to do, a direct coupling.

It’s a very specific model, a very specific agent that you discover there.

And so in some sense, free will, I think, is a perspective on decision-making under uncertainty, starting from the point where you discover your own self-model up to the point where you deconstruct it again.

And of course, you will deconstruct it again.

At some point, you will be able to fully understand how you’re operating.

And once you do this, making your decision becomes indistinguishable from predicting your decision.

Because of computational irreducibility, often you will not be able to predict the decision before you make it.

But as soon as you understand that it’s just a computational process going on, and you understand the properties of that process, you will no longer experience yourself as having free will.

Free will is a particular kind of model that happens as a result of your own self-model being a simulacrum, instead of being a high-fidelity simulation of how you actually work.

And we are young beings.

We don’t get very old.

It’s very difficult for us to get to the point where we fully understand how we work.

Except in certain circumstances, right?

When we observe our children, very often we get to the point as parents that we fully understand what they will be doing in a given situation.

And we can fully understand their own actions and anticipate their decisions.

And the child might experience that it has free will.

And we experience that the child has free will up to the point where we suddenly understand, oh, this is what’s going on.

And at this point, I can completely control the child because I can out-model it.

And it’s only to the point where this system is going to introduce levels that are, again, reaching my own level, that decisions become unpredictable.

But if I am a few levels of modeling depth above the other agent that might think that it’s free will, the free will starts to disappear from my own perspective.

And it also happens in my own mind.

There’s many things that I do.

But I thought as a child, I’m acting out of my own free will.

And now I understand how mechanical it is.

And I can deal with myself by controlling myself, by out-modeling myself successively and becoming one more complex in this way.

All right.

Stuart Hameroff

00:33:10 Stuart Hameroff

Having gone through the depths of consciousness and physical systems with Donald Hoffman, we now transition to the quantum world with Stuart Hameroff.

Hameroff’s exploration of temporarily non-local consciousness offers a different angle on the question of free will, moving from cognitive neuroscience to quantum physics.

Now, going to this backward time aspect, I heard you mention Libet’s experiments and that they don’t necessarily show a lack of free will, but perhaps the free will propagates backward in time.

Now, can you explain that?

Well, Libet did these experiments in – well, he did two sets of experiments.

The first set of experiments that Roger wrote about in his book, The Embraced New Mind, were sensory experiments where he had people in neurosurgery.

He worked with a neurosurgeon named Bertram Epstein, who, by the way, was the husband of Bertram Feinstein, who was the husband of Dianne Feinstein, the senator from California.

She’s still around.

He passed away years ago.

But he was a neurosurgeon, and Libet worked with him.

And so he had patients that he did neurosurgery on while awake.

So he would drill a hole and numb it up with local anesthetic.

Once you get into the brain, you can operate on the brain.

It doesn’t hurt, but you numb up the hole, and you can access the brain, and, for example, for the finger on the opposite hand.

So Libet did experiments like he would stimulate the finger and record from the brain and stimulate the brain and then see when the subject was conscious of feeling the finger.

So you would expect, or I would expect, not knowing anything beforehand, that if you stimulate the brain, you feel it immediately.

If you stimulate the finger, it would be a delay because it would have to get to the brain.

If you stimulate the finger, there is a delay, but it’s only 30 milliseconds, evoked potential.

So it’s pretty fast.

But if you stimulate the brain directly, you need to have ongoing activity, and it takes about a half a second, 500 milliseconds, because you don’t get the evoked potential.

But if it continues for 500 milliseconds, you do feel it at 30 milliseconds.

What’s this evoked potential?

Okay, so if you stimulate the finger, the signal, you get a spike.

That’s the evoked potential.

If you stimulate it here, you don’t get the evoked potential.

You just get ongoing activity.

It looks like gamma.

But if you do it for half a second, the patient, subject, has the conscious experience at the time of the evoked potential, 30 milliseconds.

So somehow, at 30 milliseconds, the brain knows whether or not there’s going to be 500 milliseconds of ongoing activity afterwards.

If there is, he or she reports it at 30 milliseconds.

That’s interesting.

Okay.

If there isn’t, then he or she doesn’t.

And so Libet concluded that there was a signal going backwards in time from the time of the, what he called neuronal adequacy, and that sent this information backward in time.

Now, Roger wrote about this in Emperor’s Neuron, because that can happen in quantum physics, which is temporally non-local.

Is this related to the subcutaneous rabbit?

Have you heard of that, where you come on an arm?

Yes.

So this is related to that.

Yes.

And also the color five phenomenon, where the color bounces back and forth, and it goes from red to blue, and you go red, blue, red, blue, and you can guess, and then it goes red, red, and you know you’re not fooled.

And that’s because you seem to know what’s going on.

And the cutaneous rabbit’s the same thing.

I actually wrote a chapter about it.

I can send it to you about all this.

Well, I’ve written several, actually, about it.

And all those can be accounted for, but you somehow know what’s coming.

And this is very important, because if you and I are talking, and you ask me a question, and if someone were measuring the activity in my brain for what you said, it’ll happen in, say, 300 to 500 milliseconds after they get to my ears.

But I will have responded to you at 100 milliseconds.

This is very, very standard neuroscience.

What neuroscience says about that is that I respond non-consciously and have a false illusion of answering consciously after the fact.

The consciousness is epiphenomenal.

My cognitive autopilot non-conscious self answers you, and then a little later, my conscious self says, oh, I said that.

I’m in control.

And it means that consciousness is epiphenomenal and illusory.

That’s what Dennett says.

That’s what all the big-name philosophers say, unless they have some way to weasel out of it.

But if you have backward time, it means that you can do all that, and you can still respond consciously in real time.

What does your theory have to say about free will?

Well, first of all, you need the backward time effect to be able to act in real time.

It doesn’t address determinism, because even if you do act in real time, you still have the problem, well, maybe it was always going to be that way because of everything else that’s already happened.

But when you bring in the backward time effects, I think that gives you the possibility of free will.

But you’re still governed by, if that’s true, you’re still governed by the deterministic Schrodinger equation up to that point, and maybe even the platonic values.

So, you know, the best they could say is that free will is the experience of your volition being influenced by platonic values.

Claudia Passos

00:38:47 Claudia Passos

Stuart Hameroff’s exploration of free will and temporal perception naturally transition into Claudia Paisos’ discussion on behavioral markers as indicators of consciousness.

The audio conditions were suboptimal, thus prompting me to reiterate in post-production the question for you.

The questioner was asking Claudia to expand on behavioral markers versus reflex markers.

Behavioral markers versus reflex markers.

It’s quite difficult.

So, one thing I didn’t have time to go through is how those behavioral markers would be markers of consciousness.

And there is at least one theory of consciousness that you tell us.

If the creature had what they call flexible behavior, the capacity to react with flexibility will change our behaviors regarding, for instance, pain still.

So, imagine you’re feeling pain, but you have a behavior to avoid pain, and this behavior didn’t give you weak pain, we can change your strategy to avoid feeling that way.

And this happens in some flexibility.

Usually, if you’re not conscious, you just have a kind of automatic response that is the same response all the time.

And infants, they try to change their strategies to avoid that painful state.

So, this is a kind of flexible behavior.

And, for instance, from representational experience, we’ve claimed that flexible behavior is a marker of consciousness.

And then you can claim that this behavior is a marker of flexibility and a marker of consciousness.

Wolfgang Smith

00:40:27 Wolfgang Smith

Claudia Paisos’ exploration of behavioral markers and their connections to consciousness sets the stage for Wolfgang Smith’s discourse on the relationship between free will, love, and the divine.

How does free will comport with knowing that there’s a timeless realm, so that you can see all of what occurs through time, but then if we exist as a moment in time and we’re trying to plan something for the future and we have free will, how do we have free will when from another perspective all our choices have been made or all of it can be seen?

Well, I think there’s only one answer to that question.

And that is that free will pertains to our present state, which is a state of half-knowing.

Once we attain enlightenment, there’s no question of free will.

Enlightenment (Realize Eternalism) vs. Salvation (Transcend Eternalism)

Sorry, enlightenment is the same as salvation, or is that different?

[1. On advanced Psilocybin, get enlightenment that no-free-will is metaphysically the case, per Classical Antiquity. Reach sphere 8 fixed stars, Ogdoad.

2) Receive spiritual salvation lifted above no-free-will, per Late Antiquity; reach sphere 9 outside the cosmos, at level of Prime Mover, Ennead.

– Michael Hoffman]

Well, I think nothing short of salvation would put you into that state.

Where there’s no more free will.

There’s no more free will because there is no more will in our sense of the term.

Love is what makes things real.

What do you make of that quote?

Well, I think it is based upon one of the deepest teachings of Christ.

St.

John the Evangelist, in his, I forget what it is called, his letters, not the gospel, but his letters, he says, Deus caritas est, God is love.

So love in the authentic sense that we’re using term now is itself divine.

It is God.

It’s not something that God makes, something that God creates.

Well, there is love in that sense too, but love in its highest, purest sense is inseparable from God.

Bernardo Kastrup

00:42:50 Bernardo Kastrup

Wolfgang’s peregrination of the divine and free will serves as a perfect precursor to Bernardo Kastrup’s discussion on the illusion of free will and the deterministic nature of the universe.

It is the collective unconscious.

It is the last dissociated parts of our minds or the completely non-dissociated mind at large.

That’s the natural wave.

Remember, I am a naturalist and nature is a big wave, it’s going somewhere.

We can choose to swim with it or swim against it.

You can choose to be tools of it or to rebel against it and lose.

You’re guaranteed to lose.

She’s super interesting, super interesting.

So you’re saying that nature is this huge force and it generally controls you way more than you think.

You are an aspect of it, so you’re not even separate from it.

So even to say it controls you is already a categorical mistake.

You are not distinct from it, but you just have a hallucinated narrative about what you are.

In other words, nature has a hallucinated narrative about what it is and it goes in conflict against itself because of it.

Choices are instinctive.

There is something instinctive that runs through you and it’s calling the shots, all the important shots.

The problem is we think it is us choosing it, so we rebel against it or we regret against choices and suffering pours out from that dynamics, which is also a natural dynamics.

It’s nature fooling itself, it’s all natural.

So the choice to swim with the current rather than against it, is that choice yours or is that choice ultimately another current?

In which case, you can’t- Nature can offer less resistance against itself.

Let’s put it that way.

Because you see, it’s impossible to use terms in a completely unambiguous way because the terms like I or doing or resisting or nature, they have already a social meaning.

So if I try to be completely accurate, I will contradict that social meaning and nobody will understand what I’m trying to say.

So I have to be ambiguous and seemingly contradictory perforce if I am to use language.

I don’t think Bernardo Castro exists as a true separate agency.

Bernardo Castro is a ripple or a metaphor I prefer, a whirlpool in the ocean of nature.

It’s a process, it’s a doing, it’s not a thing.

It’s a Castro-ping, not a Castro.

Yeah, I don’t know what said that.

Is that your intellectual mind saying that I don’t believe Bernardo Castro exists?

That’s my intellect saying.

Okay, but you don’t feel that in the moment, but you feel like that’s actually correct.

So let me just say that.

Matt O’Dowd

00:45:23 Matt O’Dowd

And now we transition from Bernardo to Matt O’Dowd from PBS Space Time, as Matt talks to us about the subtleties of relativity, time perception, and the universe’s self-consistency.

Consciousness is just, it is in this sense an emergent phenomenon, but there’s no very hard line, I think, for when it emerges.

You know, I started all this saying I’m no expert and then gave you this super long treatise as though I know anything, but this is the picture that feels the least contradictory to me.

So then in this view, is there such a thing as free will?

In this view, yes.

Correct my misunderstanding, Shen.

The way that I understand it is that there are some atoms moving around and occasionally that is something we call information processing.

That information processing is much like there’s a lamp right here.

That is casting onto the wall.

That wall is now the feeling of consciousness.

That is the effect.

And something is happening here.

Now that wall doesn’t cause anything with this light.

The light will move around.

Right now it’s stationary, but the light can change colors.

It can get brighter.

It can get smashed on the ground and that wall would change.

But I wouldn’t say that that wall has any causal influence on that.

So that’s what I mean when I say that it sounds like there is no free will in what has just been outlined.

So please correct my misunderstanding.

Okay, so let’s try to talk about free will.

So first of all, so Bahar, my partner, she’s a science journalist and has written a lot about these topics.

I encourage you to check out her article in The Atlantic, which debunks some nonsense on the topic.

But she always reminds me to think about these things in the context of the historical development.

So pre-enlightenment, there was this idea that free will and meaning and mind were inextricably attached to notions like God and the immortal soul.

Okay, so when those ideas started to be questioned, was the same time that the materialist paradigm arose.

So the Newtonian worldview of, you know, atoms bouncing around in the void, perfectly predictable clockwork.

So at the same time that we discarded or started to discard the spiritual, and in that gap, we inserted this sort of very first and perhaps naive mechanistic determinism, notions like free will, which were conjoined with God and the soul got thrown out with the bathwater and were replaced by the idea that these things are epiphenomena of a coal mechanistic universe.

So that’s one gripe.

What it is, it’s a gripe with the, what I think is an oversimplification of the approach to thinking about free will, but all other things related to the mind also.

So let me explain why my view doesn’t, suggest that free will is an illusion.

And so what does it mean?

It means free will means that you make, your choices are your own.

They’re not forced on you by something else.

And for any choice you make, you could have chosen otherwise.

And the standard argument is that your choices are not yours because they’re determined by the particles that you’re made of.

Okay, you couldn’t have chosen otherwise.

So this is the argument that you hear.

I won’t mention any names because, so you couldn’t have chosen otherwise because the, whatever, the exact position and velocity of all of your subatomic particles set and had to evolve according to the laws of physics.

Or that if those particles have some fundamental randomness, then the randomness is still not free will.

Okay, so that’s the argument.

And first of all, let me say that, that picture of physics is, it’s right in a sense.

Okay, so I believe that subatomic particles evolve according to the Schrodinger equation, et cetera.

And the subatomic particles have no idea that they’re in a brain or that they’re part of a choice or that they represent a data structure that’s part of, that data structure feels as part of a choice.

But the problem with this reductionist argument is that it’s messing up its definitions and in particular, its definitions of causality.

So if we think about the world as having these kind of layers of complexity, okay, you have physics driving the atoms and chemistry driving the molecules and biology driving the cells.

Then you could say something like, so if you wanna talk about causality here in terms of the hierarchies of emergence, then you could say that quarks and electrons cause atoms, atoms cause molecules, molecules cause cells, cause apples and brains and brains cause minds, right?

But this is a type of causation and it’s like this cross-hierarchical causation.

But I would argue that there’s a real fundamental difference between that type of causation to what you might call an intra-hierarchical causation that defines the dynamics within a given layer.

Can you give me an example?

All right, so you can say that there’s this causal power whereby a cell is, or say a neuron is caused by the molecules that it’s formed of.

It is an epiphenomenon of those molecules, which in turn are epiphenomena of their atoms, et cetera.

But it’s also entirely meaningful to say that an action potential in a neuron causes a downstream neuron to fire, right?

So that’s a reasonable statement.

Okay, a neuron fires one that’s attached to fires and it makes total sense.

And in a real sense, it’s true to say that the first neuron caused the firing of the second.

It’s less useful to say that the wiggle of a quantum string on the Planck scale caused a downstream neuron to fire even if the quantum string is the, let’s call it the hierarchical cause of one of the electrons in the first action potential.

That’s like a roundabout and relatively inane approach to talking about causation.

So there’s this kind of bottom-up causation in which different levels in the scale of physical scale or complexity scale are generated by the lower layers, but there’s a different type of causation within the layer.

Okay, so, and within each of these layers hierarchical layers, you have a dynamics that is in a sense independent of the layer below that generated it.

Okay, so you can, you know, I mentioned Bernoulli’s equation, fluid flow.

So you had this whole field of hydrodynamics, which is beautiful.

And in a sense, it’s causally closed.

Like you can predict anything about the behavior of fluids using these rules.

And it does matter what the properties of the particles in that layer are.

And those properties, the properties of those particles are generated by the layer below.

But once you know the properties of those particles, you don’t care about the detailed physics of the level below.

You are in that layer and the rules of that layer are in a sense closed and independent.

Okay, so brains have a dynamics of neural activity.

Okay, it’s a physical system.

They behave like some type of neural network.

We can even simulate it.

Okay, current neural networks miss an awful lot, but in principle, we’d be able to run the dynamics of the brain with a different substrate.

We can run them.

We could run, we one day probably will be able to run these in silico.

And that dynamical system, the system of…

of neural activity will be independent of the substrate once we figure out what that dynamics is.

Man, Matt, I don’t know if you realize you’re saying such controversial statements at saying in principle.

So for instance, you’re saying in principle, we could simulate the brain substrate independent.

Who knows?

I mean, well, that’s like a huge open…

I’m going to crapple over the expression in principle, I think.

Yeah, who cares?

We’re just talking and people who are listening just realize that none of us have the correct words.

And in order for us to just, in order for us to convey anything that’s non-trivial, we’re going to have to flummox and flounder.

Okay, well, I’m happy.

I’m happy to put myself out there.

I think we will be able to simulate the brain, but it might be a really long time away because there’s so much that goes on.

And the point is that once we figure out those dynamics, it’ll be independent of the substrate, silicon or meat.

So maybe we can agree that the dynamics within a layer are their own thing.

And the idea of cause within one of those layers is different to the cause that generates one layer from the layer below it.

Oh, I see what you’re saying.

Okay.

Okay.

So you have this dynamics of cause and effect in biology or in an ecological system.

Okay.

It’s true that reintroducing wolves to the Yellowstone National Park caused the deer population to become under control.

Okay.

That’s a totally meaningful statement and it would be absurd to try to do the same thing with quarks.

Okay, yes.

Yes.

Like quarks to deers, right?

So you have these dynamical systems and the cause in that sense is like…we should have a different word for it.

So we’re mixing our definitions of the intrasystem versus the intersystem causation.

So we’re still not at free will yet.

So our conscious experience may be emergent from the actions of our neurons.

It probably is in some sense.

But in another sense, it is dual to the actions of our neurons.

Okay, so our neurons have a dynamics which you can, at some level, explain their behaviour.

And they generate this pattern of information that tells a story about itself, etc.

And so, in a way, our minds or the description of our minds is just another way of casting neurodynamics.

It’s essentially a duality.

It is a dual to that system.

But in a way, you could argue that it’s more fundamental, right?

So if, in the broadest sense, our minds are the result of a computation, then our minds are also a dynamical system independent of the substrate.

So a set of elements, in this case thoughts, linked by a set of rules.

And thoughts are symbolic representations.

And so you can come up with a language that manipulates these symbolic representations and tell stories with them.

Okay, that’s in a sense what a mind is, and a bunch of other stuff.

Okay, so in a sense, psychology is the science of understanding the dynamics of that system.

And it’s, to some extent, mappable.

Maybe never completely, but you could write down the dynamics of the mind without referencing neurons.

Okay, just as you could write down the dynamics of the neurons without referencing electrons.

And the reason I said that, in a sense, the way of looking at neurodynamics, which is the dual of it, which is the subjective experience, is more predictively powerful than the neurodynamics themselves.

In some way of looking at it, that’s more fundamental.

There are things you can predict about what a brain will do and how an organism will behave that you could only get by looking at the thought dynamics, like the mental dynamics.

And you could never get by trying to look at a few neurons and guess what they’re going to do.

Is this not a difference between what we can do and what is?

I don’t think so.

First of all, let’s put a pin in the idea that the mind is its own dynamical system, potentially independent of its substrate.

Understanding the dynamics of the mind is better than understanding the dynamics of neurons for many, many things.

But does that mean that, like you said, is this just our impression?

That we can’t we can’t, for example, predict someone else’s detailed behaviour, their inclination to fall in love with particular types of people based on looking at their neurons or looking at their quarks.

Okay, so now we get to this idea of in-principle.

Yeah, okay.

That’s the title of the podcast.

Is it even in-principle possible to do so?

I would argue there also no.

It’s in-principle possible to predict some human behaviour by trying to model the physical aspect of the brain.

So here things get a little bit messy.

You could predict someone’s behaviour just by knowing them well.

Does that mean they have no free will that they couldn’t potentially do otherwise?

You could predict someone’s inclination to certain types of behaviour by knowing about any of the neuropathologies that they might have.

So for sure, the epitomes of free will.

We often fail to exercise free will, or we are predictable.

But the idea that free will is an illusion because brains are mechanistic, I think is a little fallacious.

The reason is that a brain… Because of that dual notion?

Well, not even.

There are physical-ish reasons here.

The idea is that your actions are pre-determined and predictable because they’re entirely determined by the configuration of physical matter and so on.

But then I want to ask, to whom is the brain predictable and pre-determined?

To what observer and what reference frame?

So if you have any sufficiently complex system like the brain, the dynamics are coupled across multiple physical scales.

So for example, an important part of the decision mechanism in the brain is the so-called Breitschark potential, which is basically the correlated noise in brain signal that the brain actually uses as a tiebreaker in decision making.

It partially drives the dynamics in ways that we don’t very well understand at all, because it’s super new that we figured out.

Can you repeat the name of the potential?

It’s the Breitschark potential.

It’s also called the readiness potential.

Okay.

Yeah.

You want to look at Aaron Scherger’s work.

Actually, Bahar wrote an article on this.

I’m just mentioning that because I’m super familiar with it now, but it’s just one example of how you have dynamics influenced.

In complex and even pseudo-chaotic systems, you have these dynamics linked across multiple scales of these hierarchies.

In that case, it becomes essentially impossible to predict behaviour based on the smallest elements of the substrate, whatever the atoms.

So you have this system that is partially chaotic, and it’s well-known that these things can’t be predicted without infinite computation.

I think this is a manifestation of this computational irreducibility.

My question is, what observer or what reference frame could predict your actions perfectly by knowing the exact state of all the quantum fields in your brain?

You could imagine some super-advanced alien that could somehow perfectly scan your brain and get that, and then run a simulation of your brain at the same time.

But even that, I think here, the very nature of quantum mechanics makes that challenging.

Okay, so you literally need to track every bit of quantum information in the most complex systems to make a perfect prediction.

Maybe you can make some predictions, but it’s not even practically impossible.

It’s probably even, in principle, impossible.

You have things like the no-cloning theorem, which forbids you from making a perfect copy of quantum information, which is what you would need to do to make a perfect prediction.

I think in a meaningful way, it’s in principle not possible for any possible observer to perfectly predict your choices.

It is possible for impossible observers like Laplace’s demon, who knows the exact position and velocity of every particle in the universe.

So from the perspective of Laplace’s demon, you have no free will, but Laplace’s demon is a mythical entity.

Like other mythical entities, I don’t think we should rate something an illusion, because a mythical entity could, in principle, predict your behaviour.

So there’s this guy named David Wohlpart.

I don’t know if you know him, but he’s in Santa Barbara, I believe.

He has the limits on inference machines, which says that even Laplace’s demon in Newtonian mechanics can’t exist.

I agree that Laplace’s demon cannot exist.

I think even relativity forbids Laplace’s demon, because there’s a limit to how quickly it could.

Anyway, this is a whole other topic.

Long story short, I think free will is real in a meaningful sense.

Going down the definition of real is like a whole other podcast, but free will is real in a meaningful sense, because choice is a fundamental, dynamical component in a particular dynamical system whose behaviour is independent of its substrate.

Whose behaviour is not fully predictable in the context of its substrates, by mapping its substrates in a way that is possible for any entity that could exist.

If you choose to not believe in free will, then at least you have that choice.

Yeah, okay, great.

Man, there’s so much that we could talk about.

Okay, how about instead of delving more deeply into it, I’ll just tell you the one thought, I’ll just tell you one of the thoughts.

Why is this notion of to who important?

For instance, we can say, there is a computer here.

We consider that to be an objective fact.

We don’t say this computer is here to who, unless you are someone who believes that the observer creates the reality.

So let’s disregard that interpretation and say there’s an objective reality.

So why is it that we’re saying free will exists to who?

Why can’t we just say free will exists in the same way that this computer exists?

Yeah, I mean, we live in a relative universe.

Particles have a relative existence.

You know, Hawking radiation only exists if you’re a certain distance away from a black hole.

Unruh radiation only exists if you’re accelerating.

So there is a sense in which the frame of reference is critical.

And for non-noisy… There’s something noisy about the radiation and the unruh radiation, so the Hawking radiation in that one.

Yeah, well, I think so.

Maybe I do.

I don’t know.

But there is something non-trivial about the relativity of existence in terms of matter, for sure.

This is something I don’t think we’ve properly wrapped our heads around.

Maybe it’s as confusing as the measurement problem.

The idea that the universe can and does look radically different, depending on your frame of reference.

And the only thing that is consistent is the self-consistency of the universe itself.

No matter what changes based on your frame of reference, how you choose to make measurements, for example, in things like a Bell test, these things can radically change what universe you see.

The one thing that never changes is that the universe remains self-consistent for all observers.

Okay.

Can you explain what that means?

Is that different than the statement that the laws of physics are the same?

Well, in the simple case of relativity, let’s take the simple case of the twin paradox.

This is this thought experiment in relativity where a pair of twins jumps in a spacecraft and zips off at a large fraction of the speed of light and comes back several years later from the perspective of the twin at home.

The twin at home has aged and the twin who traveled is much younger because time ticked slower for the twin who was traveling because of their relative speed.

Okay, so from the point of view of the traveling twin, they didn’t think that their clock was ticking.

They were looking back home and they thought that at home the clock was ticking fast.

No, wait on.

No, I should know this stuff.

So, this is a so-called paradox.

You should watch this PBS Space Time.

Yeah.

The way it works is that when you observe a clock that’s traveling at some speed, that clock appears to tick slow.

So, fast-moving objects, the time slows down.

Both twins see each other’s clock as ticking slow because the spaceship is moving fast.

But then for the astronaut twin, Earth appears to be moving backwards quickly because speed is relative.

There’s no preferred inertial frame of reference.

So, Earth erases away.

That twin’s clock seems to slow down.

Yet, when the twin gets back home after that long trip, the twin who stayed at home…so, it has to end up being consistent.

Which one aged more than the other?

The answer is that there is a self-consistent answer.

When they get home, both of them agree that the twin who stayed home aged more.

But how can that work if both of them saw the same change in each other’s clock?

Both of the twins have an answer for that.

Their answers are different, but they lead to the same conclusion.

The twin who was at home sees the traveling twin’s clock tick slower so that the traveling twin ages less and gets home.

Meanwhile, the one at home is waiting and getting older, and his twin comes back much younger because less time passed.

But for the traveling twin, they watch the twin at home and they watch the twin at home’s clock tick slower.

In fact, the traveling twin feels themselves aging faster until the moment that they turn around.

In order to turn around and come home, they have to accelerate.

The other thing that Einstein’s relativity tells us is that if you are deep in a gravitational field, your clock ticks slower.

The amount that that twin has to accelerate in order to return home causes their clock to slow down enough that, from their perspective, the twin who was at home not only caught up to them, but aged a lot more.

They both have different stories about why they both agree that the traveling twin is younger than the stay-at-home twin.

Curt, how did we get to this?

This was in service of a point.

Okay, so firstly I was asking about what does it mean to be self-consistent?

Yeah, yeah.

The universe will always conspire to be self-consistent and that observers will ultimately agree.

I have so many questions here.

That’s even the case with particles.

If you see under radiation, I can’t remember what the solution to this one is.

Someone else doesn’t see under radiation, but they see…

If you accelerate fast enough, then you’ll be incinerated by what’s the equivalent of Hawking radiation.

It’s a type of horizon radiation.

Someone who is not accelerating doesn’t see your particles and yet does see you incinerated.

So why does the person who’s not accelerating see you incinerated?

I think the answer is they see you being incinerated by something else, like the drag on the quantum fields or something.

I don’t recall, but there’s a neat answer.

The universe keeps conspiring to give us these neat answers that everyone ultimately is going to agree, even if the universe that they think they live in looks wildly different to the universe of the next person.

The consistency conspires to always be there.

I think there’s a mystery there.

Now that you’ve heard from Matt O’Dowd of PBS Space Time, the following is Anand Vaidya on free will.

Anand Vaidya

01:19:06 Anand Vaidya

Anand is one of those rare philosophers who’s well-educated in both the Eastern philosophical tradition and Western analytic tradition, particularly Indian and modal philosophy.

Enjoy.

What are your thoughts on free will?

Um, what are my thoughts on free will?

Do you feel like there’s pressure to go in the direction of there is no free will?

No, it’s actually the opposite.

I had this really interesting dinner with Richard Swinburne, one of the leading philosophers of religion in the world, and I had a dinner with him and my wife in Romania.

And we ended up talking about free will, and I just told him, like, I never got into the problem of free will because I think I just was full-blown committed to the idea that free will and determinism are incompatible, and we have free will.

Otherwise, I can’t make sense of – yeah, maybe I’ll repeat the same sort of thing I said to him that I say to all my students and everybody when they ask me about free will.

There’s two things about free will I care about.

One is the thing I’m about to say, and the other is the relationship, again, between artificial systems and freedom and artificial systems and free will.

So, I’m very interested in those.

So, here’s the first one.

I think speaking a language and communicating with someone is an agential activity involving free will at some level and degree of freedom in the choice of constructing sentences and embedding them with meaning to communicate them, so that if we don’t have free will, I’m not talking right now.

No, there’s nothing – it’s a parrot.

There’s nothing going on there, right?

So, parrots are merely under one understanding, simply repeating sounds that they’ve heard without any sort of choice about it in terms of the free construction of meaning.

So, if I don’t have – so, one way to make it clear is some people think about free will only in relationship to bodily action.

I think about free will in terms of its relationship to mental action.

Speaking is a mental act.

So, if I don’t have free will, I don’t have any mental actions.

If I don’t have any mental actions, then I’m not speaking, because speaking is a mental action.

That’s the first point I care about in terms of free will.

I bring this up a lot.

So, yeah.

Then the other one that I bring up is that I’m not so sure that there’s some kind of free will that we have that machines are incapable of having because they’re so-called programmed in some way.

And in fact, I just saw this wonderful episode of Star Trek, it was in the Voyager, Thoth, where they in fact had a discussion between the doctor who is a hologram and one of his assistants, and the doctor said to the assistant, um, well, I don’t choose anything when I give a diagnosis.

I’ve been programmed to give the diagnosis based on these vast amounts of information that I’ve been trained on.

Like, this is the hologram, this is the doctor talking to their assistant about a patient that they have, and expressing himself that he doesn’t have choice or free will in diagnosis and that he simply takes the data that’s been given to him, runs it through all the data he has known before or been given, and then spits out a diagnosis.

And then she says this brilliant response.

She says, well, what’s the difference?