Cybermonk December 20, 2020

Study version of “Mushroom-Trees” in Christian Art (.pdf)

Contents:

- Summary

- Figure 1 – Plaincourault Fresco

- Figure 2 – Baptistry Mosaic, Henchir Messaouda

- Figure 3 – Lions Mosiac in Tunisia

- Figure 4 – Photo of Pinus pinea; Umbrella pine; Italian pine

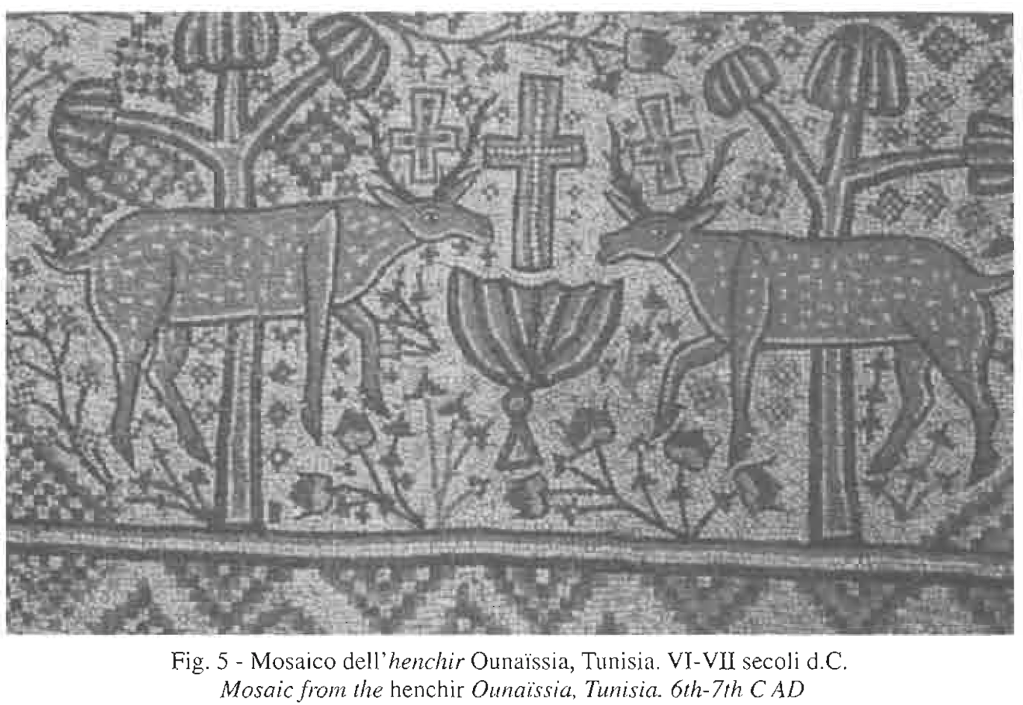

- Figure 5 – Mosaic from Tunisia

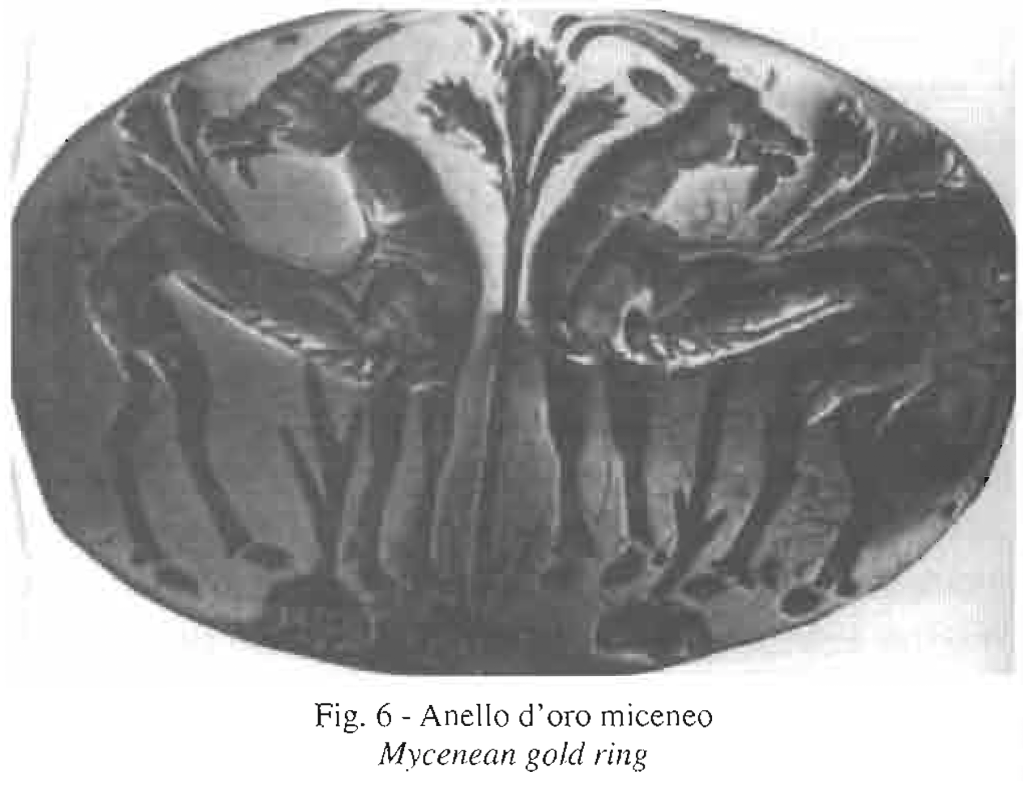

- Figure 6 – Mycenean Gold Ring

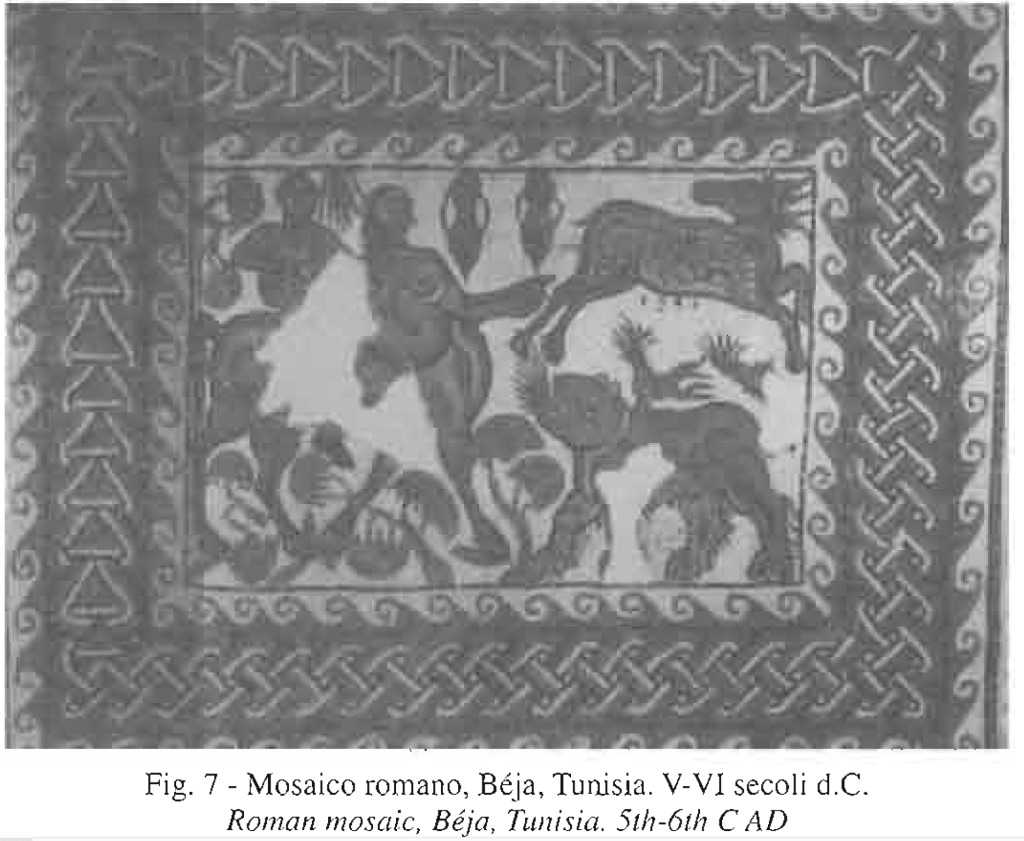

- Figure 7 – Roman Mosaic in Tunisia

- Figure 8 – Abbey of Saint Savin

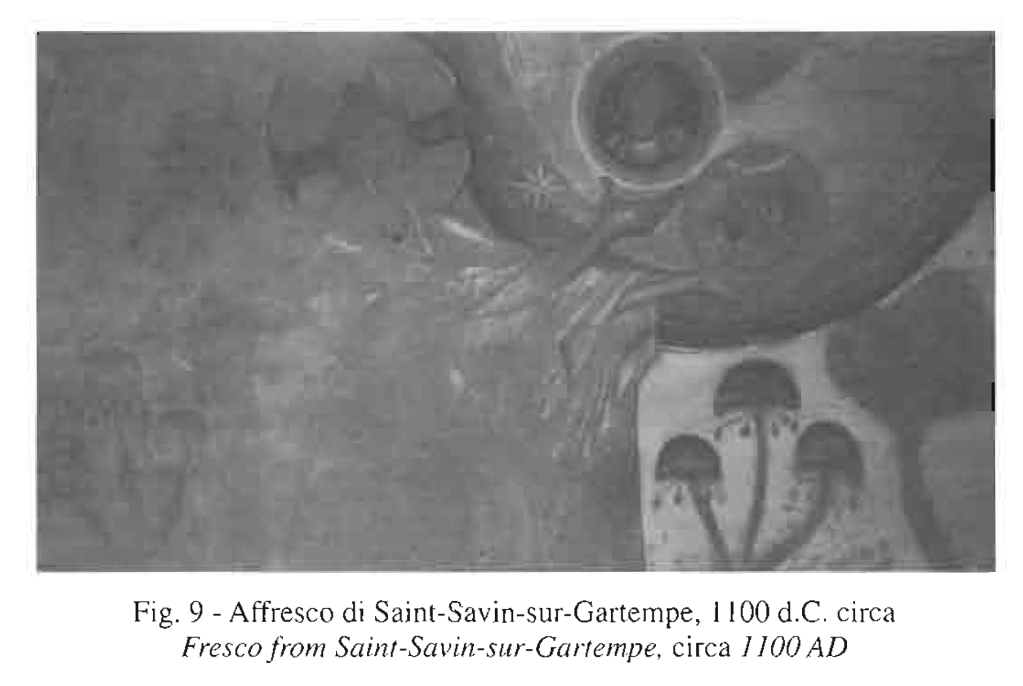

- Figure 9 – Saint Savin Fresco

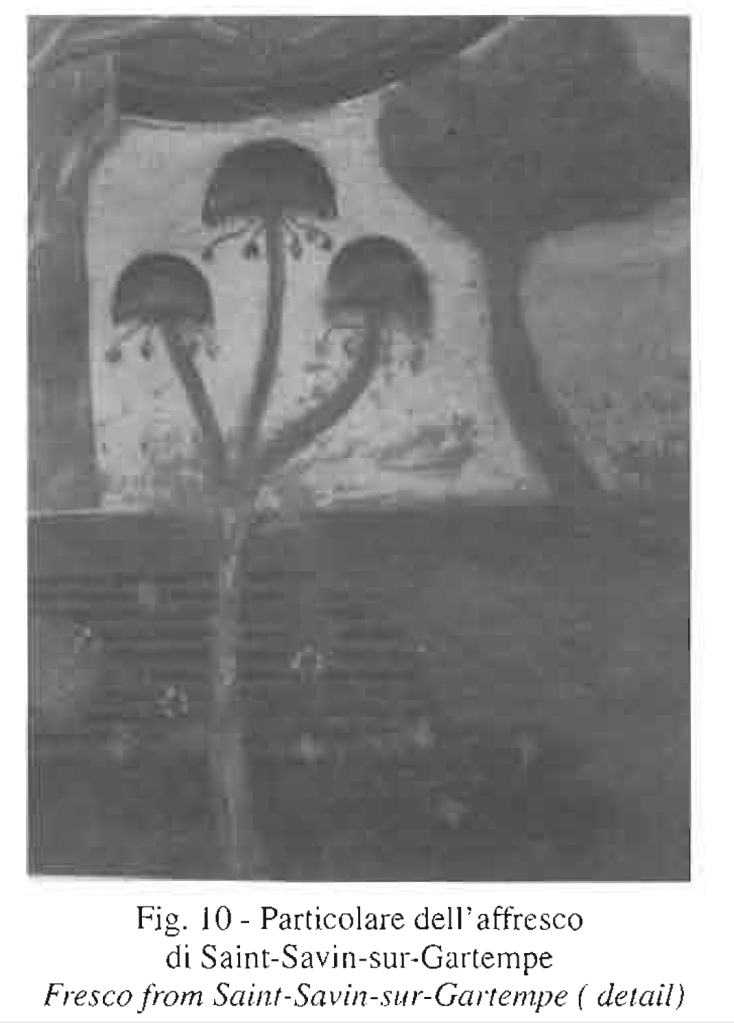

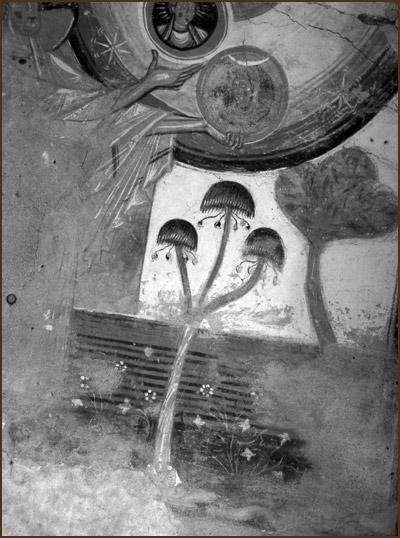

- Figure 10 – Fresco from Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe

- Figure 11 – Panaeolus Specimen Photo

- Figure 12 – Carmina Burana: The Forest

- Figure 13 – Church of Vic

- Figure 14 – Jesus’s Entry into Jerusalem, Church of St. Martin de Vicq

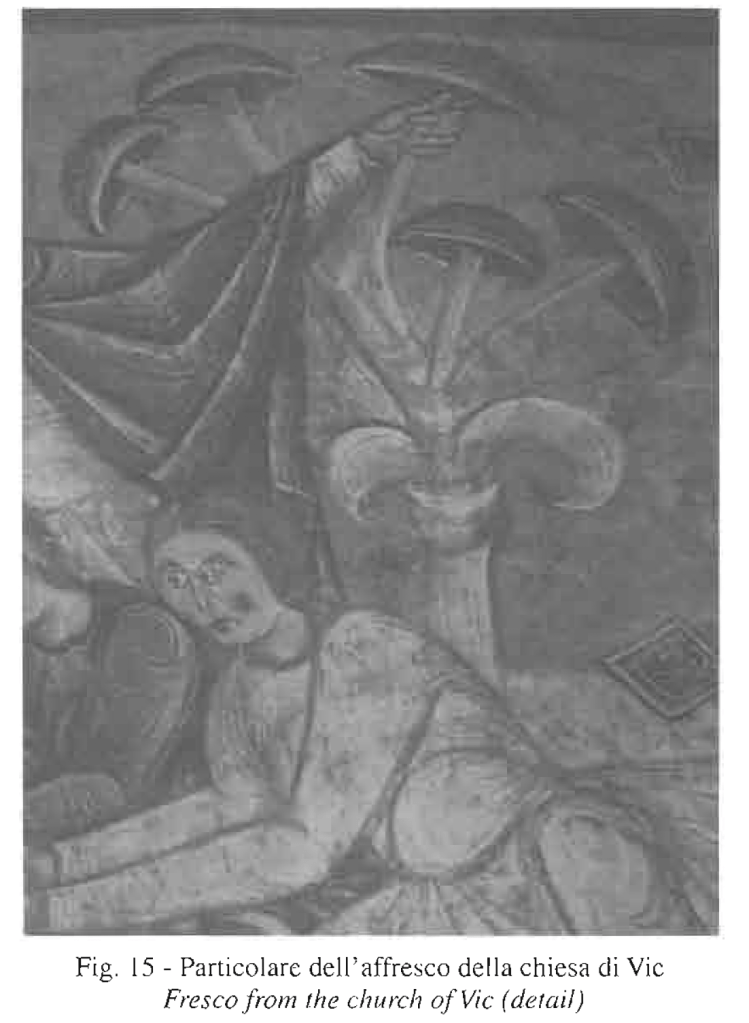

- Figure 15 – Jesus’s Entry into Jerusalem, Church of St. Martin de Vic

- Figure 16 – Crucifixion with Psilocybe Trees & Amanita Trees

- Figure 17 – Salamander in Bodleian Bestiary

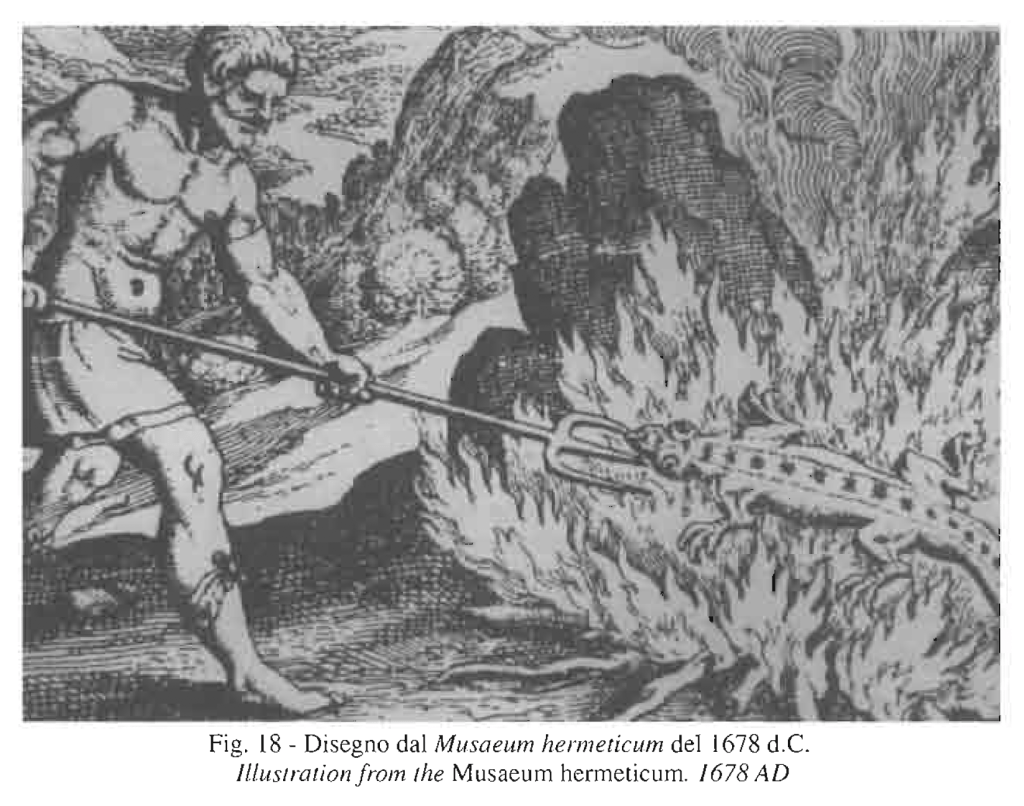

- Figure 18 – Musaeum hermeticum roasting salamander

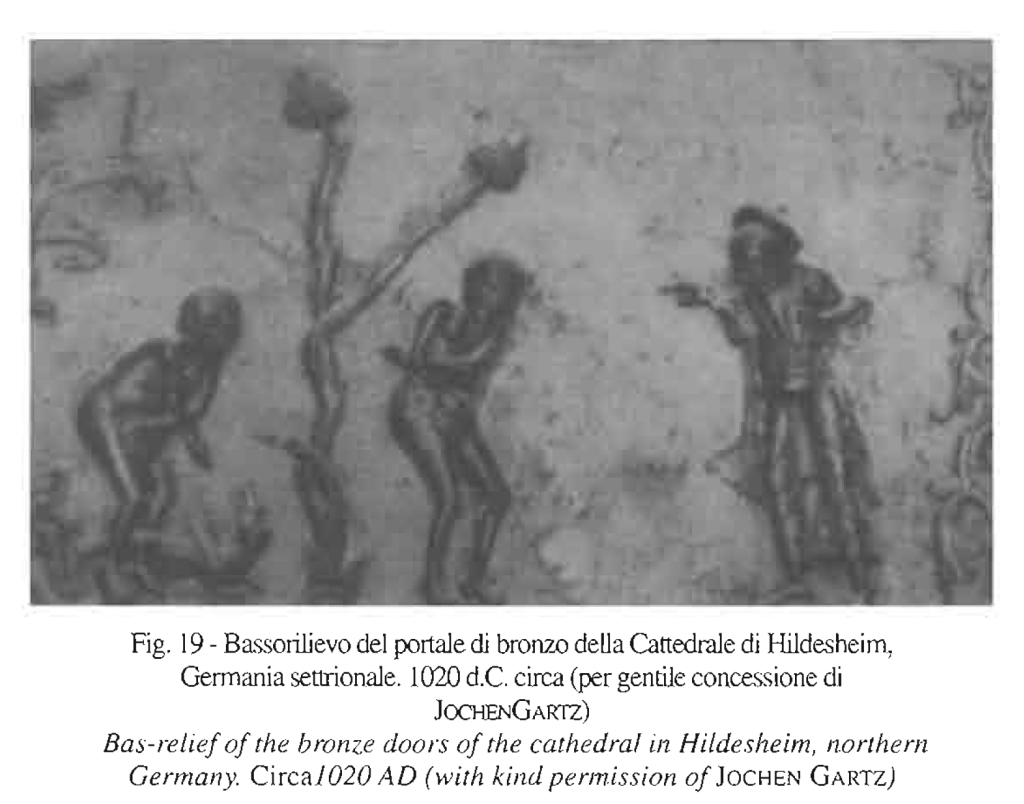

- Figure 19 – Hildesheim Doors (Bernward)

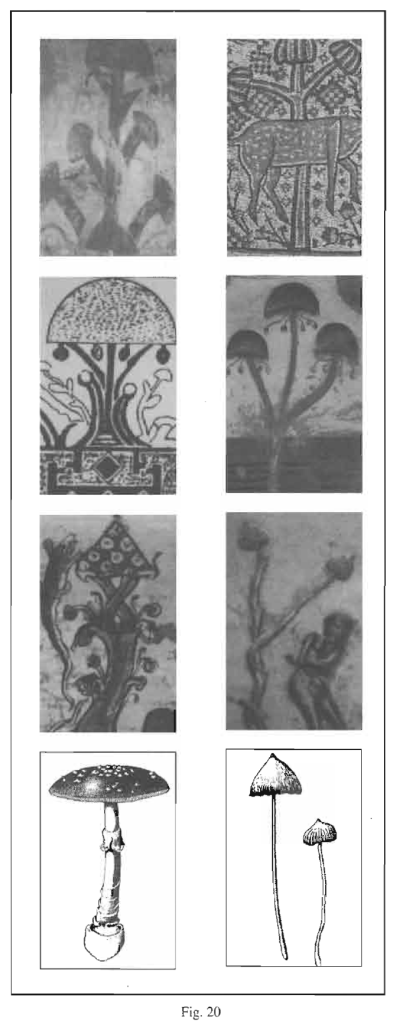

- Figure 20 – Table: Column 1: Amanita Mushroom Trees, Column 2: Psilocybin Mushroom Trees

- Figure 21 – Basilica of Vezelay, France

- Figure 22 – David & Goliath, Capital No. 50, Basilica of Vezelay, angle 1

- Figure 23 – David & Goliath, Capital No. 50, Basilica of Vezelay, angle 2

- Figure 24 – Bishop of Tours, Capital No. 26, Basilica of Vezelay

- Figure 25 – Basilica di Aquileia

- Acknowledgments

- Bibliography

- Notes by Cybermonk

- Citation & Link for “Mushroom-Trees” in Christian Art (Samorini 1998)

- About this Page (M.H.)

- The Role of Mushrooms in Christian Art (mh)

- How the “Evolutionary Anthropology” Approach Is Utilized to Suppress Mushrooms in Christian Art by 50-100% (mh)

- Information About the Article (mh)

- Samorini’s Article “The mushrooom-tree of Plaincourault”

- Weblog Notes by Cybermonk

- See Also

Summary

In this article, various examples of the so-called “mushroom-trees” to be found in early and mediaeval Christian art works from a number of churches in Tunisia, central France and other regions of Europe are presented and discussed.

The author makes it clear that the works of art presented here are considered from the point of view of the possible esoteric intention of the artists in their inclusion of the mushroom motif.

This paper, based on the most recent research, reaches two main conclusions.

Firstly, the typical differentiation among the “mushroom-trees” of these works would appear due to a natural variation among psychoactive mushrooms.

Secondly, on the basis of analysis of the works in question, a call is made for a serious and unprejudiced ethnomycological study of early Christian culture.

Figure 1 – Plaincourault Fresco

[proxy for the war of the mushroom-problem -cm]

Site Map > Plaincourault-Fresco

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/nav/#Plaincourault-Fresco

Christian Mushroom Trees

Gallery page at Egodeath.com in support of my 2006 Plaincourault article.

http://www.egodeath.com/christianmushroomtrees.htm#_Toc134497555 -mh

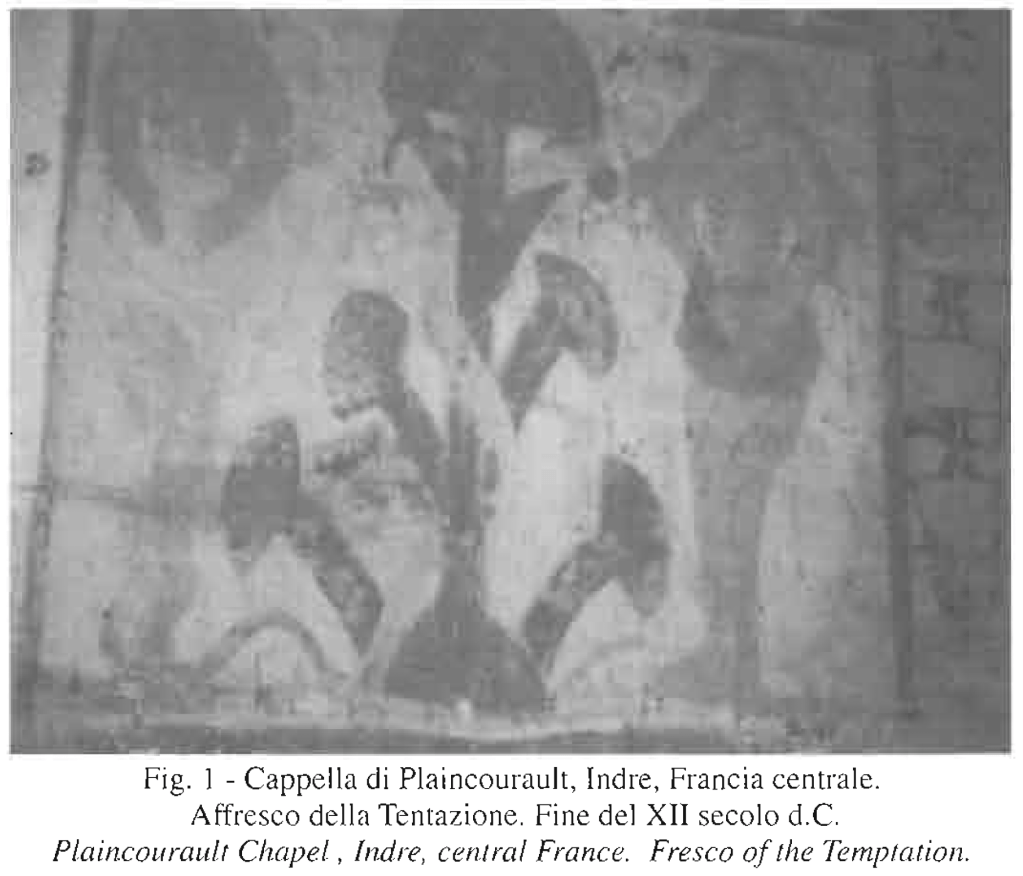

In an article published in the previous issue of this magazine, I presented a discussion of the mushroom-tree in the famous frescos of the Romanesque chapel of Plaincourault in the province of Indre in central France (SAMORlNI 1997).

_____

During a visit in May 1997, I was able to examine the frescos of the chapel (and also note their state of deterioration).

Here, we find the scene of the Temptation with its mushroom-tree painted by the Knights of the Order of Malta on their return from the Crusades.

_____

By way of summary of my earlier article, I observed that the Plaincourault mushroom-tree is to be found in the scene of the Temptation from the book of Genesis.

It appears between Adam and Eve, with a serpent coiled around it -in its mouth the fruit it offers to Eve.

_____

According to the historian of Christian art, Erwin Panofsky (cf. WASSON 1969: 179-180) this type of tree which resembles a mushroom and which, for this reason, is termed Pilzbaum (“mushroom-tree”) in German – is widespread (above all, in Romanesque and early Gothic) Christian art.

It has been considered the schematic representation of a conifer (the “umbrella pine”) and there are hundreds of examples illustrating the graduai transformation from the naturalistic forms of the pine to the more schematic “umbrella-tree”, hence to the various forms of mushroom-tree.

_____

Toward the beginning of this century, a French mycologist put forward the hypothesis that the Plaincourault mushroom-tree was a representation of Amanita muscaria, the well-known psychoactive mushroom with its whitespotted red cap.

lf this is the case, the esoteric content of the Temptation would appear evident -i.e. identification between the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and a mushroon capable of producing visionary states and “illumination”.

_____

After a hurried visit to the chapel in Plaincourault and, above all, after consulting the art historian Panofsky, R. G. Wasson categorically denied the validity of the interpretation offered by the French mycologist and supported and propagated by his followers.

In his essay on Soma (1968: 179-180), Wasson, the father of modern ethnomycology, after citing Panofsky’s comment, stated “it would have been better if the mycologists had consulted the art historians”.

[Why? To be impressed by the “celerity with which” these trained-dog artists blurt-forth the correct, stock, cover-story, pseudo-explanation for the problem that plagues the field? That there are so damn many mushrooms in Christian art.

Wasson wrote privately to mycologist Ramsbottom “Rightly or wrongly, we are going to reject”, Ramsbottom published the letter, Wasson didn’t realize that til long after, was displeased to discover caught out making arbitrary declaration of rejecting the mushroom image as a mushroom. Wasson’s pronouncement of rejection “rightly or wrongly” had been revealed in Ramsbottom’s mycology book for a long time. -mh]

Article:

Wasson and Allegro on the Tree of Knowledge as Amanita

Section: Wasson, 1953

http://www.egodeath.com/WassonEdenTree.htm#_Toc135889190 —

“Rightly or wrongly, we are going to reject the Plaincourault fresco as representing a mushroom. This fresco gives us a stylized motif in Byzantine and Romanesque art of which hundreds of examples are well known to art historians, and on which the German art historians bestow, for convenience in discussion, the name Pilzbaum. It is an iconograph representing the Palestinian tree that was supposed to bear the fruit that tempted Eve, whose hands are held in the posture of modesty traditional for the occasion. For almost a half century mycologists have been under a misapprehension on this matter. We studied the fresco in situ in 1952.” – Wasson, private letter of December 21, 1953, quoted (unknown to Wasson) in Ramsbottom, Mushrooms & Toadstools, post-1953 printing, p. 48

_____

Closer examination of the facts reveals that, in a footnote in his Mushrooms, Russia and History, Wasson had already stated even more forcefully that “The Plaincourault fresco does not represent a mushroom and has no place in a discussion of ethno-mycology.

[you can bank on Wasson’s credibility & lack of bias -mh]

“It is a typical stylized Palestinian tree, of the type familiar to students of Byzantine and Romanesque art” (WASSON & WASSON 1957, 1:87).

_____

As I have already noted on a previous occasion (SAMORINI 1997) and as the evidence I present here would suggest, Wasson’s conclusion may be considered premature.

However, it must be remembered that, according to J. OTT (1997), Wasson was unable to advance research into the Plaincourault “case” on account of his fundamental research and discoveries in Mexico and concerning the Vedic soma.

Nevertheless, I feel this hardly justifies his hasty dismissal of this idea.

_____

I might add that Wasson’s probable “oversight” does not in any way diminish the credibility or stature of the father of modern etnomycology.

I stress this point because the direction I have taken in my studies has as its starting point the trail blazed for mycologists by Wasson’s critical works.

Four Features of the Plaincourault Image, 1

With the premise that the problem of interpretation of the evidence consists in establishing the intention of these artists to represent the mushroom symbol as part of the esoteric content of their work, we may now consider a detailed description of the evidence.

_____

In the Plaincourault mushroom-tree form (Fig. l), we may note the following details:

1) the semispherical foliage or fronds is similar to the cap of a mushroom and is studded with spots (in this case, whitish on an ochre background);

2) two of lateral ramifications join the frond-cap from below and symmetrically in relation to the main trunk of the tree.

These two ramifications may be intended as a means of representing the three dimensions of the tree with a serpent coiled around its trunk.

From the mycological angle, however, these ramifications might represent the membranes enveloping mushrooms of the family of the Amanitas at the early stages of development.

This membrane then breaks when the cap broadens out and separates from the stalk;

3) the roundish fruit of the tree is, here, held in the mouth of the serpent as it offers it to Eve;

4) along and around the base of the main trunk we have ramifications which are also very similar to mushrooms in form surmounted by “caps” upon which once more we may note whitish spots.

_____

I have also studied a number of other mushroom-trees characterized by the same four iconographic features found at Plaincourault.

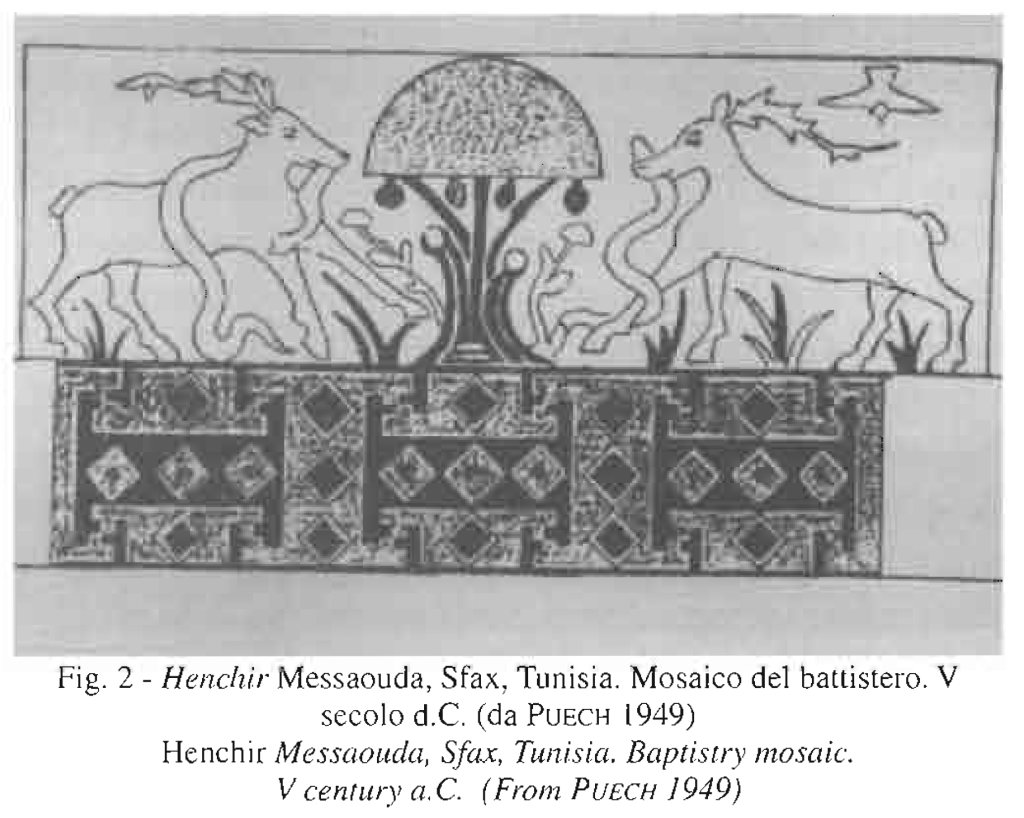

Figure 2 – Baptistry Mosaic, Henchir Messaouda

Two examples are to be found in 4th and 5th century B.C. Tunisian mosaics. In Tunisia during the centuries of Roman domination (I st-4th centuries B.C.) there was a flourishing tradition of well-crafted mosaic work of considerable artistic value.

This tradition was continued in the mosaic floors of the first Christian churches (FANTAR 1995). The mosaic in fig. 2 decorates the baptistry of the henchir Messaouda in the Tunisian region of Sfax.

lt probably dates back to the 5th century a.c., and here we have an iconographic scheme which was fairly widespread and of very ancient origin: two animals symmetrically placed beside the Tree of Life.

_____

The first representations of this arrangement date back to Sumerian art of the 3rd millennium B.C.

The two animals are generally of the same species; they are horned wild animals or quadrupeds (above all, Cervidae) or birds.

The object placed between them is the Tree of Life.

A typical example is the two wild animals beside the sacred tree Horn (Haoma) of Persian art.

Similar representations exist, such as a Plant of Life, a recipient containing the Water of Life, a Tree of Life from the foot of which rivers of the Water of Life spring forth (usually, four rivers are represented), or even a column (as in the famous “Door of Lions” at Mycene surmounted by two lions rampant upon a column).

Sometimes the two animals feed on the Tree of Life or drink from the Chalice or the springs of the Water of Life.

This variant is probably closest to the original iconographic scheme.

This artistic scheme originates in the Middle East and spread to much of the Old World including North Africa as it underwent local stylistic modifications.

According to FANTAR (1995: 107), the Phoenicians brought it to Africa, where it passed into the hands of the Romans.

_____

The Tree of Life is the element most subject to stylistic variation, from the most realistic to the most imaginative.

The palm-tree is one of the most widespread types.

lt may be more or less realistic, or represented by a single palm leaf the size of a tree.

A further common type in the Mediterranean basin is the conifer-tree, sometimes represented quite simply by a pine cone.

The mushroom-tree, which appears to derive from the conifer tree, seems to be less widespread than the other two types mentioned here.

_____

Christianity was one of the last and most important means by which the artistic scheme of the two animals and the Tree of Life spread.

The two most frequently adopted animals were two lambs or two fishes. The Cantharos (chalice) of the Water of Life or the Cross gradually took the place of Tree of Life.

The esoteric meaning of the scene also changed, as CHARBOJ\lNEAU-LASSAY (1997: 54) has pointed out:

“When, in the iconography of the first centuries of Christianity, two fish or animals surround an emblem, this always directly represents Jesus Christ; and the animals which accompany Christ are the symbolic representation of the Christian faithful”.

With the transformation of the Tree of Life into a Cross we therefore have an identification between the Tree and Christ.

The Water of Life, placed in the Cantharos, and which flows from the Tree of Life becomes more and more c10sely identified with Christ’s blood.

_____

On further examination of the Messaouda mosaic, we may note that the two animals are deer, both of which are savaging a serpent.

The deer savaging a serpent is also an iconographic scheme of pre-Christian origino This motif is associated with the belief, recorded by writers in antiquity, that deer were fierce foes and persecutors of serpents (cf. CHARBONNEAu-LASSAY 1994; see “Deer”, l :XXX; PUECH 1944).

{deer with branching antlers vs. serpent} = possibilism vs. eternalism. -mh

Four Features of the Plaincourault Image, 2

The tree placed between the two animals is a mushroom-tree of the same kind as that found at Plaincourault and it is endowed with the same four characteristics mentioned above, namely,

I) the cap-shaped fronds, with many spots;

2) the two lateral ramifications of the main trunk joining the frond;

3) the round fruits (here, hanging from the frond) and;

4) the fungoid protruberances at the foot of the tree.

In the upper right corner of this scene we may note a dove, a widespread feature of Christian art with a great variety of meanings.

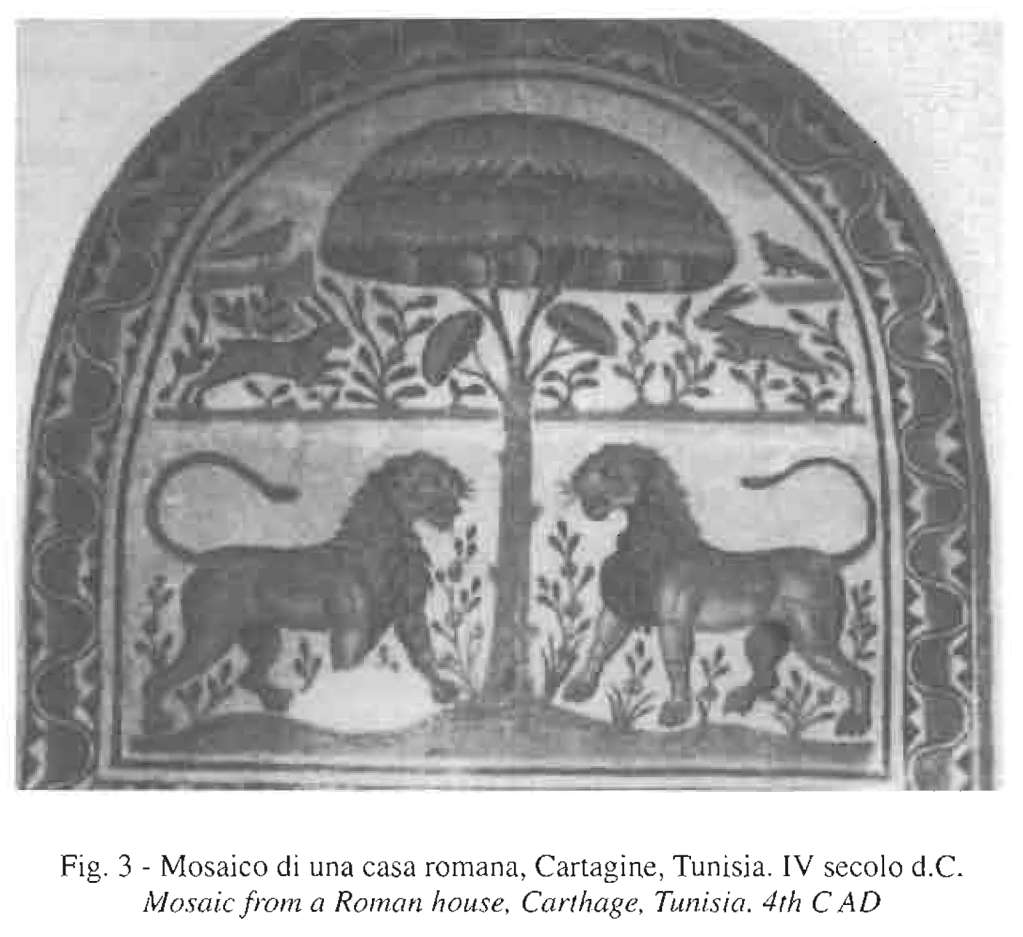

Figure 3 – Lions Mosiac in Tunisia

1. Caduceus = branching vs. non-branching experiential mental worldmodels

2. Caduceus = male ruler snake & female ruler snake, frozen in rock

The same artistic scheme is featured in another 4th century A.D. Tunisian mosaic (fig. 3; cf. FANTAR 1955: 107) from Carthage, now in the Bardo Museum in Tunis.

This mosaic was discovered in a Roman house and not in a Christian church.

Not only do we find the main pair of animals, two lions, but also other pairs, hares and birds (probably doves) in the upper half of the scene, these two symmetrically arranged around the tree.

The tree is rendered fairly realistically and, indeed, it might be considered a conifer-tree, despite the presence of the four characteristics of the Plaincourault and Messaouda mushroom-trees which ascribe it to this type of representation.

The Carthaginian mosaic tree would appear to be midway between conifer-tree and Plaincourault-type mushroom-tree.

If this is the case, it might be considered a (pre-Christian) prototype of this mushroom-tree.

The fruits of the Carthage mosaic tree are represented with the characteristics of a cone, and this is the main detail which provides the identity of conifer.

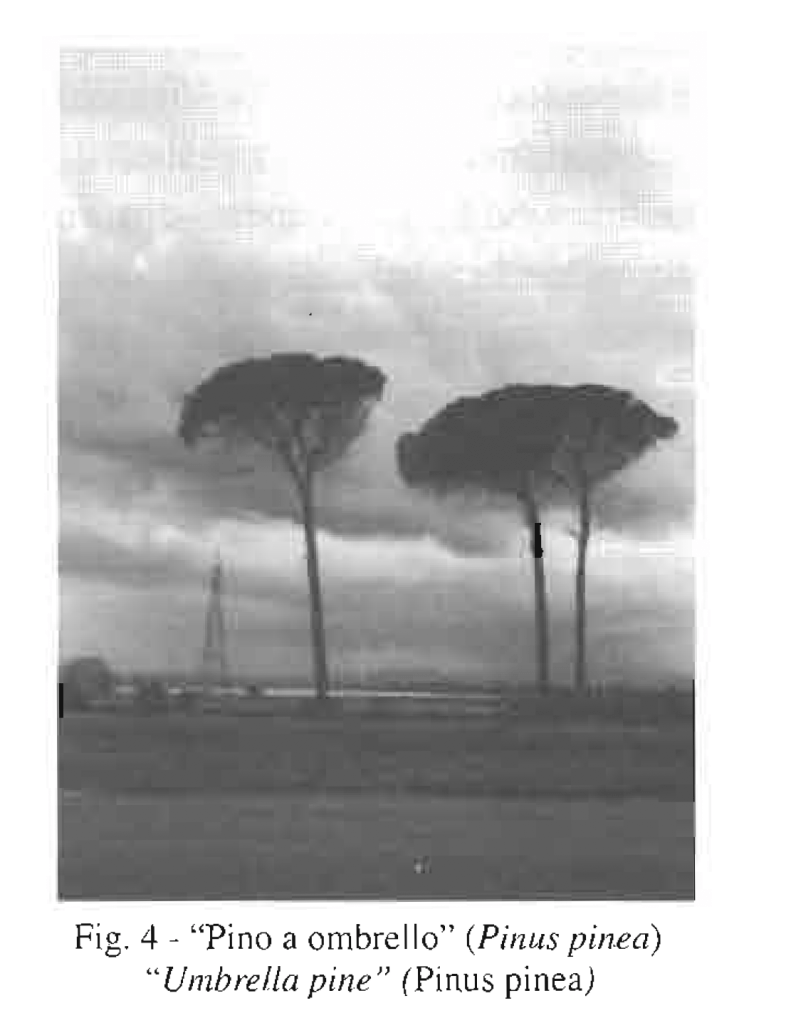

Figure 4 – Photo of Pinus pinea; Umbrella pine; Italian pine

[Page: Christian Mushroom Trees, Michael Hoffman

Subsection: Italian Umbrella Pines

http://www.egodeath.com/christianmushroomtrees.htm#_Toc134497557 ]

Art historians, inc1uding Panofsky (cf. WASSON 1968: 179), believe this conifer-tree form corresponds to Pinus pinea, the “umbrella pine”, a common Mediterranean pine (cf. fig. 4).

This conclusion is probably correct for the Carthaginian mosaic and any number of other examples of conifer-tree, but less appropriate for the Plaincourault and Messaouda mushroom-trees and others which I shall mention shortly.

[“This conclusion” — that’s vague. Is Samorini asserting that certain trees in art mean only trees, and not mushrooms (disagree); or that the mushroom depictions are styled to look similar to certain types of trees (agree)? weak writing/theorizing -mh]

We should also bear it in mind that the mycological interpretation does not rule out the dendrological (pine) interpretation, or vice versa, given the ecological association between conifers and certain species of mushrooms, notably Amanita muscaria.

[he’s right, but incomplete logic. I want him to say the poetic truth “a mushroom can mean a mushroom and a tree.” He only presents a literalistic connection. -mh]

Figure 5 – Mosiac from Tunisia

[I identify these as Psilocybe, Amanita, Psilocybe -mh [1:29 a.m. December 26, 2020]

]

We also find another kind of mushroom-tree in Tunisia.

This is from the henchir Ouna’issia (6th-7th century), at the moment housed in the Museum of Sbeitla (fig. 5, cf. FANTAR 1995 :229).

We might consider this scene a transition stage in an iconographic scheme which is only slightly different from that of the two animals symmetrically placed beside the Tree of Life; it might be considered a variant of a scheme which also originates in the Middle East and dates back to remotest antiquity.

Here we have the two animals and three Trees or Plants of Life which are usually the same as each other, one between the two animals and the other two behind them.

Figure 6 – Mycenean Gold Ring

A fine example comes from the Mycenean gold ring in fig. 6, in which three trees or plants are combined with two quadrupeds, apparently steinboks.

_____

During the last stage of absorption of this artistic scheme in Christian art (i.e. its full transformation into a “truly” Christian symbol) we may note the recurring image of the two animals combined with one or more crosses.

As we have already indicated, the Trees of Life become the symbol of the Cross, once Christianized, and the three parts constituting many examples of a certain type of Tree of Life (e.g. in the Mycenean ring) become the three upper components of the Cross, the various stages of the “crucifixion” of the Tree of Life become evident in paleo-Christian art.

_____

The Ouna’issia mosaic represents a stage in the transition of this iconographic scheme: the two animals are symmetrically placed and are once more two (ochre-coloured and white-spotted) Cervidae;

the tree placed between the animals has already completed its transformation into a “cross”, and, below it, there is a Cantharos containing the Water of Life (at this stage, perhaps already considered the blood of Christ).

We may also note that the other two Trees of Life, placed behind the animals, have not yet been fully ‘crucified’.

These two trees are mushroom-trees of a different kind than the Plaincourault one.

Both feature the three cap-like fronds and, upon these, vertical lines have been traced which we may consider “striations”.

Figure 7 – Roman Mosaic in Tunisia

In another 5th-6th century mosaic from the Béja region in Tunisia, housed in the Bardo Museum in Tunis (fig. 7, cf. FANTAR 1995:92-3), we find a mushroom-tree similar to the Ounai”ssia example.

This mosaic represents a Greek mythological scene in which Achilles receives instruction from Chiron, the wisest of the Centaurs, on deer hunting.

{wisdom = loss of control} -mh

A Chimera is presented in the lower left [sic, right?] corner.

Achilles and Chiron are surrounded by four plants of the same shape, and on careful observation we may consider them mushroom-trees.

Probably for reasons of space, three of these are composed of two mushrooms but the fourth has three.

Each of the frond-caps presents lines in various colours which remind us of the “striations” encountered in the Ouna’iss ia mushroom-trees.

Some of these lines overlap the lower edge of the frond-cap.

This kind of mushroom-tree has been called “tree with medusa-shaped frond” (RJOu 1992).

Mycologically speaking, these overlapping Iines recall the filaments which adorn the edges of the caps of various species of psychoactive and non-psychoactive Panaeolus-type mushrooms.

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=Panaeolus

_____

In fact, ROBERT GRAVES associated the mythological figure of the Centaur with psychoactive mushrooms in his essay Food for Centaurs (1960, cf. 1994).

[everyone is perfectly vague but best I can make out, the original title was Centaurs’ Food, in 1956 -mh]

However, the arguments he used were unthorough and perhaps a bit fanciful.

Says Samorini who demonstrates his expert arbitrariness, who speculates “these mushrooms probably don’t represent mushrooms, but these other ones probably do”. My assignment system is fairer: MUSHROOMS MEAN MUSHROOMS. Who is stupid and closed-minded: the artists, or the academic art historians?

Why is Samorini going around left and right baselessly assuming and declaring that most artists are ignorant, and then dismissing the mushrooms that they painted? Is this article covering mushrooms, or covering-up mushrooms? -mh

FANTAR (1995: 92) comments on the Béja mosaic, the work of Christian artists who revived pagan symbols and mythologies, and stresses the point that it dates back to a period of heresy and fratricide due to struggles among various groups of Christians.

Figure 8 – Abbey of Saint Savin

We find mushroom-trees which are similar to the Ouna’jssia examples in a fresco dating back more or less to the same period as the Plaincourault mushroom trees, and from the same area (central France).

This fresco is in the Abbey of Saint-Savin-sur Gartempe (Fig. 8) in the province of Vienne, about 40 kilometers from Poitiers and only 9 kilometers from Plaincourault.

The Abbey’s frescos are among the most highly admired works of French Romanesque art.

They are dated circa 1100, about 80 years before the Plaincourault frescos and , Iike these, are of the HautePoitou Romanesque Style (OURSEL, 1994).

Figure 9 – Saint Savin Fresco

the Fruit Defendu and the Flesh of the Gods

https://www.paperblog.fr/5834996/le-saint-graal-retrouve-le-fruit-defendu-et-la-chair-des-dieux/

On the ceiling above the central nave of the church at a height of about 16 metres, there are some scenes from the Old Testament.

Figure 9 presents the scene of the fourth day of Creation with God placing the Sun in the firmament in the presence of two trees which could hardly be considered mere ornament.

One of these is a mushroom-tree.

The moon and sun are anthropomorphically depicted, each featuring a head within a medallion.

_____

In the same Fig. 9 we see part of the preceding scene (which has somewhat deteriorated) depicting the third day of Creation – the day of the creation of vegetation.

Here, we see two trees of two types (one, a mushroom tree) which are also like the ones on the right. A third tree of the same kind is depicted elsewhere among the nave frescos next to the scene of Moses in the presence of the Pharaoh (Rrou 1992: 35).

We should also bear in mind that the Saint-Savinsur-Gartempe frescos include many other trees which also have a fairly tall trunk which is often above a sort of ring.

The trunk spreads out to form a number of branches, generally three, and some branches terminate with a compact trilobate frond.

A number of these trees spring from a small conical base or mound which might represent a mountain (RIOU 1992).

It has been suggested that the pictorial cycle of SaintSavi n-sur-Gartempe contai ns stylistic influences of the Byzantine art of northern Haly (cf. LABANDE-MAILFERT 1974).

Figure 10 – Fresco from Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe

The mushroom-trees are all the same.

They have a large trunk encroaching downwards upon the lower scenes of the same wall, as we may note in the detail provided (fig. lO).

These trees are also similar to the Ouna’)’ssia mushroom-trees.

Here too, they present three mushrooms with striated “caps”.

_____

Scholars have termed this kind of vegetation “mushroom tree”, or even “tree with medusa-shaped frond” (R10U 1992).

Alternatively, it has been defined “mushroom-shaped flowers” (THOUMIEU 1997: 134). ELEMIRE ZOLLA (1979) seems to have no hesitation at all as to the inspiration of the Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe mushroom-trees: they are hallucinogenic mushrooms, “symbols of the divine, and of exceptional powers”.

Figure 11 – Panaeolus Specimen Photo

As stated above, in reference to the mushroom-tree from the Béja mosaic (fig. 7), the striations hanging over the “frond” [“canopy”; cap] are very similar to the fringes on the caps of various species of Panaeolus.

These striations are more a feature of mushrooms than trees; very many mushrooms present these striations, some of which are psychoactive.

In fact, the mushroom striations are caused by the juncture between the gills and the cap (see fig. II).

The four curious adornments under each cap terminate with a small round object which might symbolize the fruit of the mushroom tree.

Figure 12 – Carmina Burana: The Forest

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/CarminaBurana2.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carmina_Burana

Plate 8 from Brinckmann’s book

ivy-vine leaves in proximity with mushroom caps

My WordPress page:

Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings (Brinckmann 1906) — Plate 8

Book at archive.org:

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n77/mode/2up

Brinckmann’s book, Plate 8

ivy-vine leaves in proximity with mushroom caps

My WordPress page about Brinckmann’s book:

Tree Stylizations in Medieval Paintings (Brinckmann 1906) — Plate 8

Brinckmann’s book at archive.org:

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_8AgwAAAAYAAJ/page/n77/mode/2up

Samorini article continues:

In Fig. 12, we see the frontispiece of a German edition of the Carmina Burana. This edition is dated to the early 12th century and is housed in the Munich Staatsbibliolek.

Various types of tree are depicted; they are quite bizarre, although they do have a common source: the large group of artistic forms which developed in the Mediterranean from the Greek period on (GRABAR & NORDENFALK 1958).

One of these trees, which is very small, in the middle of the top half and upon which a bird perches, is a mushroom-tree of the Saint-Savin type, made up of three mushrooms with striated caps.

mh notes:

The Great Mycologists vs. Art Historians Dispute over Plaincourault & Mushroom Trees

Mycologists:

- Ramsbottom-Rolfe-Brightman

- vs.

- Art Historians + Bank PR

- Brinckmann

- Panofsky

- Wasson

Panofsky’s Censored Pair of Letters to Wasson Revealed and Transcribed

February 5, 2023

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2023/02/05/panofskys-censored-pair-of-letters-to-wasson-revealed/

Panofsky’s letter which Wasson censored and published multiple times – BEWARE OF ELLIPSES:

http://www.egodeath.com/WassonEdenTree.htm#_Toc135889188 — excerpt from my 2006 article:

Erwin Panofsky wrote to Wasson in 1952:

… the plant in this fresco has nothing whatever to do with mushrooms … and the similarity with Amanita muscaria is purely fortuitous. The Plaincourault fresco is only one example – and, since the style is provincial, a particularly deceptive one – of a conventionalized tree type, prevalent in Romanesque and early Gothic art, which art historians actually refer to as a ‘mushroom tree’ or in German, Pilzbaum. It comes about by the gradual schematization of the impressionistically rendered Italian pine tree in Roman and early Christian painting, and there are hundreds of instances exemplifying this development – unknown of course to mycologists. … [<– Gord, be sure to censor this Brinckmann cite -thx – the Pope] What the mycologists have overlooked is that the medieval artists hardly ever worked from nature but from classical prototypes which in the course of repeated copying became quite unrecognizable. – Erwin Panofsky in a 1952 letter to Wasson excerpted in Soma, pp. 179-180

/ end of mh article excerpt.

Samorini article continues:

As Panofsky notes (in WASSON 1968: 179), there are many mushroom-trees in Romanesque art (more than l present here).

Apart from the types described above, there are others the styles of which are derived from local variants and individual imagination.

Figure 13 – Church of Vic

One example is the mushroom tree in the magnificent frescos in the small church in Vic (fig. 13), once more in centraI France in the Berry region some 80 kilometers from Plaincourault (fig. 13).

These 12th century frescos are the work of an anonymous artist, as are most of the works l present here.

They therefore follow the Saint-Savin works, which are themselves only slightly earlier than the Plaincourault frescos.

Although these frescos do not represent the Haut-Poitou Romanesque Style they are nevertheless considered part of the same artistic tradition (GRABAR & NORDENFALK 1958).

Figure 14 – Jesus’s Entry into Jerusalem, Church of St. Martin de Vicq

https://psychedelicgospels.com/psychedelic-gospels-book/

https://psychedelicgospels.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/09.3-St.-Martin.jpg

Commentary by Cybermonk:

Below, in 1998, is maybe where some misleading wording originates, as we see in John Rush 2011/2022 claiming that this image “clearly shows mushrooms being handed out”, or per Browns’ 2016/2019 fantasy interpretation/ projection/ hallucination, “Strictly reporting what we see, we see tops that have been obscured or made not visible above the stems, of the plant-like gifts offered to Christ who reaches out to receive them” — wrong, wrong, wrong.

In the next sentence, Browns write “stem … mushroom”, making it clear that by “stem”, Browns mean mushroom stems, following John Rush’s bad lead.

These are all misreadings and projecting onto the image things that are not shown in the image, as is Samorini’s misreading/ mis-description “flowers” and “leaves”.

There are no flowers, leaves, “tops”, or mushrooms shown.

https://previews.agefotostock.com/previewimage/medibigoff/8b6ecbc54bf13b7a9a8d09f0be5039d4/dae-10400530.jpg

“agefotostock-com entry jeru recolored hands sticks.jpg” 17 KB [11:04 p.m. February 9, 2023]

In fact, Jesus holds out finger shapes that contrast branching vs. non-branching, and the tree-guy puts near that an equivalent contrast, by holding in right hand non-branching sticks and branching feathers.

Saint Martin Frescos 🌴🔪🍄🖼🔍🔬🧐

February 11, 2023

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2023/02/11/saint-martin-frescos-%e2%9e%b3%f0%9f%96%96%f0%9f%8c%b4%f0%9f%94%aa%f0%9f%8d%84%f0%9f%96%bc%f0%9f%94%8d%f0%9f%94%ac%f0%9f%a7%90/

Decoding Browns’ Saint Martin Fresco: Mushroom Trees, Branches, Tree Shapes, Knives, Donkey, Finger Shapes, Youths, Gated Stone Wall

September 7, 2022

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2022/09/07/decoding-browns-saint-martin-fresco-mushroom-trees-branches-knives-donkey-youths-gated-stone-wall/

Samorini article continues:

As Manuel and Dona Torres pointed out to me, the scene of Jesus entering Jerusalem is presented in the upper part of the right wall of the choir (fig. 14).

Christ is riding a donkey.

Some people welcome Christ by laying their cloaks on the ground while others pluck flowers and leaves from the trees and offer them to him.

The trees are stylized as palms in the manner of a familiar and fairly widespread typology.

Figure 15 – Jesus’s Entry into Jerusalem, Church of St. Martin de Vic

https://psychedelicgospels.com/psychedelic-gospels-book/

https://psychedelicgospels.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/09.3-St.-Martin.jpg

https://psychedelicgospels.com/psychedelic-gospels-book/

https://psychedelicgospels.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/09.3-St.-Martin.jpg

See also:

Saint Martin Frescos

Feb. 11, 2023

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2023/02/11/saint-martin-frescos-%e2%9e%b3%f0%9f%96%96%f0%9f%8c%b4%f0%9f%94%aa%f0%9f%8d%84%f0%9f%96%bc%f0%9f%94%8d%f0%9f%94%ac%f0%9f%a7%90/

Decoding Browns’ Saint Martin Fresco: Mushroom Trees, Branches, Tree Shapes, Knives, Donkey, Finger Shapes, Youths, Gated Stone Wall

September 7, 2022

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2022/09/07/decoding-browns-saint-martin-fresco-mushroom-trees-branches-knives-donkey-youths-gated-stone-wall/

Samorini article continues:

However, the upper part of one of the trees is quite unusual (see detail, fig. 15).

It terminates with five umbrellas and may be defined a mushroom-tree.

The mushroom-like appearance is further confirmed by the concave “caps”, as depicted.

Here, we might say, we have a “mushroom-palm”.

Figure 16 – Crucifixion with Psilocybe Trees & Amanita Trees

Mushroom-trees can also be found in twentieth century folk religious art which -iconographically speaking are the outcome of developments taking place in the Middle Ages or in even remoter epochs.

See, for example the Rumenian painting reproduced in fig. 16, which my Bolognese colleague Dr Guido Baldelli kindly brought to my attention.

Many folk crucifixions are to be found in the houses of Rumenian farmers.

During the various periods of the Middle Ages the mythological image of the Tree of Life rising out of the Cross of the Passion of Christ and extending its branches was commonly encountered, as was the belief that the Cross itself had been made out of the wood of the Tree of Life (cf., for example, COOK 1987).

We note the presence of the mushroom-tree, or rather of groups of mushroom trees springing up alI over the Cross in Rumenian paintings of the kind presented here in fig. 16.

The “caps” are red with white spots, like the fly-agaric.

Another interesting detail is the inclusion of smaller striated caps.

It would appear that this kind of painting, after centuries of reproduction, combines two different kinds of mushroom-trees which, despite all, may each be identified separately even today.

_____

Rather than transmitting esoteric messages indicating some knowledge of psychoactive mushrooms, it is more likely that the folk artists of today are quite simply reproducing stereotyped images in pictures such as these, and are quite unaware of any mycological interpretation of their work.

[Academics use as their basis, assumptions from 19th C evolutionary anthropology: people before wonderful us, were idiots, artists too ignorant to know that a mushroom image means mushrooms.

This baseless assumption that artists were idiots, justified by employing 19th C evolutionary anthropology, then enables art historians to get rid of 90% of mushrooms in Christian art. That’s the excuse to suppress 90% of mushrooms in Christian art. -mh]

_____

However, if it is recognized that during the Middle Ages knowledge of the psychoactive properties of mushrooms stili existed, it is more likely that this was the intention in older representations.

Here, the indications are few and far between, and it must also be noted that research of this kind has been very scarce indeed.

[Samorini demonstrates his fine-detailed, fine-grained expertise, a kind of precision-ESP. My ESP is not so fine-grained: I simply hold that all mushrooms in Christian art mean mushrooms. -mh]

Heading 1

There are quite a few psychoactive mushrooms in Europe.

Not only do we have the two species, Amanita muscaria and A. pantherina – which require conifer or birch woods in their habitat (forests which were much more common and extensive than they are today) – , we also find a few dozen species of psilocybian mushrooms including the genera Psilocybe, lnocybe, Pluteus and Panaelous (to be found both in fields and forests, on the plains and in mountainous regions) (FESTI 1985; GARTZ 1996; GuzMAN 1983; STAMETS 1996).

_____

While there are few ethnomycological data concerning the relations between these mushrooms and European peoples, the most interesting findings concern the Iberian peninsula.

_____

lasEP FERICGLA (1993) found traces of the use of flyagaric in the 20th century on the southern side of the Pyrenees in Catalonia.

His research shows that until the first decades of this century, A. muscaria was consumed (by shepherds, charcoal burners, and isolated peasants) in the remoter rural areas – and today there are those who consume it “just to get high” and no longer for reasons concerning religious life or magic.

[That’s a false dichotomy and a judgmental insult. Samorini’s precision-ESP is here on display again: he can not only look at a mushroom image and tell whether the artist understood that a mushroom represents a mushroom; he can even look at a peasant and tell whether they take Amanita for religion, or for magic, or, on in contrast, to get high. -mh]

_____

In any case, there is a colloquiai Catalan expression, estar toeat de bolet C’to be touched by the mushroom”) referred to one acting or saying completely crazy things.

This would appear to reflect once widespread knowledge of the inebriating power of certain mushrooms, above all the oriol fol (falsa oronja) or matamosca (A. muscaria) (FERICGLA 1994: 177-184).

[Catalans are “without thinking” and are “unaware”.

Samorini thinks “drive you mad” is opposed to “inebriating”. -mh]

Nowadays, the Catalan expression is used without thinking about whence it carne or how it derived, just as mushroom gatherers in northern Italy refer to inedible mushrooms asfunghi matti (“crazy mushrooms”), unaware of the fact that this expression has broadened its meaning over time and once referred to certain mushrooms which “drive you mad” or which are, rather, inebriating.

[Dumb country folk are unaware of the psychoactive properties of Liberty Caps – they call Psilocybe semilanceata a “witch carrying a pointed object” -mh]

Psilocybe semilanceata may be found close by in the Basque country.

Although it is a mushroom with which people are familiar, they are apparently unaware of its psychoactive properties; its vernacular name is sorgin zorrotz (BECKER 1989:243), a term which refers to the figure of the witch.

1. M. FERICGLA (1998) translates this Basque term with the Castilian term bruja picuda, as in bruja que tiene pico, literally “witch with a point”, that is: witch carrying a pointed object.

This brings to mind the traditional image of the witch with her pointed hat.

This piece of etymological information might confirm the hypothesis that the witch’s pointed hat was a representation of a psychoactive mushroom such as witches may well have consumed.

Likewise, the hypothesis put forward by a number of researchers (cf., for example, CALVETTI 1986) that Little Red Riding Hood’s headgear originally represented the cap of the fly agaric, as might the hoods of other woodland folk from European folk and fairy tales.

[The people who are unaware (see above) have not forgotten (see below). Samorini judges them as consistent. -mh]

In any case, the Basque term, sorgin zorrotz is one of the few instances recorded up to the present in which psilocybian mushrooms have perhaps not been forgotten but are still referred to by traditional names (names of some consistency, given the allusions to which they might have).

_____

In Aragon, bordering Catalonia, 19th century bronze medallions have been discovered, showing the devil beside what might be “hallucinogenic” mushrooms (GARI 1996).

_____

It may be appropriate at this stage to bring up Robert Grave’s recollections of a visit to Portugal:

“Some years ago, I learned that a number of Portuguese witches made magic use of some varieties of mushroom and I arranged that the most famous mycologist in Europe, my friend Dr. Roger Heim, receive a sample [of these mushrooms].

If I remember correctly, they were panaeolus papilionaceus.

The document is in Wasson’s possession” (GRAVES 1984: 132-3; cf., also, id. 1992: 52).

Although Graves is not considered entirely trustworthy since, as we noted above, some of his interpretations are perhaps a bit fanciful , this episode bears investigation.

[Graves is wrong, although maybe he’s right, since we don’t know anything yet and need to begin looking into it. -mh]

GRAVES IS FANCIFUL, UNLIKE MYSELF, WHO AM RELIABLE WITH MY PRECISION-ESP, ABLE TO JUST LOOK AT A PAINTING OR PEASANT AND TELL WHETHER THAT PARTICULAR ARTIST OR PEASANT IS AWARE OF PSYCHOACTIVES. -MH

_____

In Italy I recently discovered a 1880 use of A. muscaria apparently for pleasure in the province of Milan, in an area in which, according to folk tradition, this kind of mushroomfa cantare (“makes you sing”) (GRASSI 1880; cf. SAMORINI 1996).

_____

In 1990, in the journal Nature, Daniele Piomelli advanced the unlikely hypothesis that St. Catherine of Genoa entered a state of ecstasy after (perhaps unwittingly) consuming A. muscaria.

ProMELu’s evidence (1991) is a passage from the biography of this saint -who lived between the years 1447 and 1510 -in which reference is made to “Aloe epatico” (hepatic aloe) and “agarico pestato” (pounded or crushed agaric) which the biographer understands to be unpleasant-tasting preparations used as condiments by the saint in order to deny herself any pleasure in alimentation.

However, as Tjakko Stijve points out, “there is no reason to believe this ‘agaric’ was A. muscaria.

Fly agaric is not bitter tasting and the term ‘agaric’ in the 15th century was widely used to indicate Agaricum officinale (VilI. ex Fr.) Donk which, in its dry form, was a commodity considered beneficiaI.

Furthelmore, A. officinale is very bitter, but it does not act on the centrai nervous system” (STlJVE 1994).

By way of confirmation of Stijve’s conclusion, it is worth noting that even as far back as Dioscorides and Pliny, the term agaricum was associated with this polyporaceous mushroom (LAZzARI 1973).

_____

JONATHAN OTT (1998: 131-2, n. 70) refers to an illustration appearing in a work on Gnosticism by RANDOLPH KURT (1987) in which, in a fragment of a Manichaean miniature, probably of French origin, the “Feast of Bema” is depicted with Mani beside the “table of God” on which there is a basket containing bread and red “sacred fruits” with white spots, like the cap of fly-agaric.

WASSON also (1968:71-6) had already stated that there may be a link between this mushroom and Manichaeism.

[Pope ok’d Wasson revealing mushroom use among heretics -mh]

_____

Turning to central and eastern Europe, we may consider Jochen Gartz’s observations: “Clusius (1525-1609), the great physician and botanist, discovered the bolond gomba in Hungary.

This mushroom was known under the German name Narrensch wamm (“fool’s mushrooms”).

It was used in rural areas, where it was processed into love potions by wise men or javas asszony. At about the same time, this “fool’s mushroom” was documented in Slovakja as well.

In addition, the mushroom found its way into the verses of Polish poet Vaclav Potocki (16251699), who refers to its potential for “causing foolishness much like opium does”.

Similarly, in England, John Parkinson’s Theatricum Botanicum (1640) includes details about a “foolish mushroom“.

The Austrian colloquial expression “he ate those madness-inducing mushrooms” (er hat verriickte Schwammerln gegessen) refers to states of mental confusion. Historic source materials such as these are scarce and widely-scattered. Undoubtedly, they refer to psychotropic mushrooms” (GARTZ 1996:11-12).

[Samorini thinks it no problem to equate “foolishness” and “madness”, but 2 pages earlier, he draws a distinction between “drive you mad” & “inebriating”. Such subtle precision is beyond my IQ level. I’m sure he’s not just posturing with his ever-unpredictable and inconsistent, arbitrary assessments and air of precision; it’s just over my little head. -mh]

_____

I remember the old Croatian myth preserved in folk tales, according to which the fly-agaric springs up on Christmas night (H. Kleijn 1962; ciI. in MORGAN 1995: 1167).

Heading 2

With regard once more to mushroom-tree representations, we cannot be sure that the artists wished to represent psychoactive mushrooms; indeed, it is unlikely that this was the case.

[unlikely on what bias — on what basis? -mh]

However, in the two examples I present below we have good reason to suspect that the artists wished to supplement the depicted scenes with an esoteric message associated with psychoactive mushrooms.

[and what would be this soul-shaking esoteric message that’s “associated with psychoactive mushrooms”? let me guess… “IT’S A MUSHROOM!!”

😱😱 –> 🍄 <– 🤯🤯

OMFG TOTALLY NO WAY!!! WOW THAT IS *SO* PROFOUND & ESOTERIC! THATS LIKE, HERMES’ CADUCEUS-LEVEL ESOTERIC MESSAGING -MH]

Figure 17 – Salamander in Bodleian Bestiary

Folio 027v (Bodleian Library, Medieval Bestiary)

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2020/12/13/images-of-mushrooms-in-christian-art/#Salamander

Analysis (2020/11/13):

Article title:

Defining “Compelling Evidence” & “Criteria of Proof” for Mushrooms in Christian Art

Section heading:

The Fire-Transformed Salamander-Serpent and the Two Legs

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/defining-compelling-evidence-criteria-of-proof-for-mushrooms-in-christian-art/#DTOC-The-Fire-Transformed-Salamander-Serpent-and-the-Two-Legs

Feb. 26, 2023 note: I found the upstream official source image a couple days ago: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/05f663d9-1fcb-4750-9ce3-03d0eb687648/surfaces/ca3ce84c-c589-4340-afa6-0733ecce5acf/ .

My main page about this image:

Salamander Mushroom Tree Right Side Cut (Dancing Man; Roasting Salamander Bestiary Image)

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2022/04/13/salamander-mushroom-tree-right-side-cut/

Samorini article continues:

CHRlS BENNETT and LYNN and JUDY OSBURN (1995) wrote an essay on the history of Cannabis, one page of which is dedicated to A. muscaria.

Here they present the surprising image (fig. 17) taken from a 14th century manuscript on alchemy from the Bodleian Library in Oxford (England).

Bennett and Osburn comment as follows: “… the alchemical painting show a man intoxicated on Amanita muscaria mushrooms.

He clutches one mushroom in his [floating left] hand as he dances about [left leg floating in thin air, right leg holding him up based on the ground] holding his other hand [stably on the right side of his] to his forehead as if the revelation is too intense.

Behind him a tree grows with a spotted mushroom for a top” (BENNET et al., 1995: 240).

The tree in question is a mushroom-tree of the Plaincourault variety.

[I’m very impressed with this precision-classification. I can’t follow his categorization scheme, but that must be because I’m stupid, not because Samorini is being totally arbitrary and applying pseudo-precision. Learned, learned! -mh]

It presents the four particularities described above. [Find above, “Four Features of Plaincourault Image” (2 headings) -mh]

The impression is that the man may be dancing; however, he may be swaying as a result of the overpowering effect of the mushroom.

[Analysis: https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2020/11/13/compelling-evidence-criteria-of-proof-for-greek-bible-mushrooms/#tftssa -mh]

This latter impression is confirmed by the fact that his hand is on his forehead in the typical manner of a person in a state of mental confusion, inebriation or dizziness.

These signs are characteristic of the onset of the effects of fly-agaric.

If we follow this line of interpretation, and accept Bennett’s and the Osburns’ hypothesis that the object in the man’s left hand is also a mushroom, we are justified in thinking that the author of this manuscript intended to draw the tree with the semblance of a mushroom, and not just any mushroom; it is A. muscaria.

[Artists are too dumb to think of blending elements of Cubensis, Liberty Cap, & Amanita, as seen in Canterbury Psalter; so they just drew a green and blue Amanita cap to represent Amanita. totally makes sense.

The artist of the bestiary salamander mushroom tree drew a fantastical hybrid of Amanita (spots), Cubensis (blue), and Liberty Cap (spear shape), including the stem {branching into two} like a {caduceus}. -mh]

This very picture, which we might consider an alchemical puzzle, parts of which we are trying to uncover, includes other interesting symbols.

Beside the Amanita-tree we see one salamander, and another one above a fire.

Here we find the first confirmation of something I personally have suspected for some time now, and that is that the salamander in certain circles engaged in alchemical studies during the Middle Ages may have been a secret symbol for fly-agaric (due perhaps partly to the fact that the cap of the mushroom and the skin of the salamander are both maculate [spotted https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=salamander ]).

The alchemical salamander, which Pliny called animal stellatum, is the Salamandra salamandra L., and is popularly known in Italy as the salamandra pezzata (pied salamander).

According to Duccio Canestrini, “in all likelihood, on seeing salamanders coming out of damp tree trunks -their favoured habitat –to escape fire, the legend came about that these animals were incombustible” (CANESTRINI 1985:27).

In ancient times it was believed that salamanders could survive in the midst of fire and would not be consumed by flames, and as time went by they became gradually more closely associated with fire.

If the hypothesis be correct that in certain alchemical circles the salamander symbolizes fly-agaric (and fig. 17 would seem. to corroborate this), the familiar symbol of the salamander above a fire might, in these circles, represent the drying of the cap of the fly-agaric.

It is well known that fly-agaric must be dried before it is consumed to obtain the full effects (cf. FESTI 1990: 171).

Figure 18 – Musaeum hermeticum roasting salamander

In the mediaeval alchemical and heraldic repertory, the iconographic scheme of the salamander in the midst of flames is generally unaccompanied by other elements. However, the scene presented in fig. 18 (taken from the Musaeum Hermeticum of 1678) is more complex. The man appears to be moving the salamander toward the fU’e with his trident as though he wished to toast it. This is not the widespread allegory of the salamander which can brave the flames without getting burnt; this is instead an operation of the Opra depicted in the manner of an alchemical allegory (the salamander is immersed in flames due to the action of man; man is cooking it, or drying it, as one does with flyagaric before consuming it for its inebriating effects).

_____

Actually, I well remember the extraordinary page from the well-known alchemical treatise by Salomon Trismosin, Splendor solis (first edition 1582), presented and discussed by CLARK HEINRICH (1994: 167-9 and table 41). In it, the winged Divine Hermaphrodite with its two heads is represented as if it were standing on only one leg.

_____

It holds two objects in its hands. These objects, given their form and color, fairJy closely resemble the lower part of the cap and the ovule from which the fly-agaric grows. Furthermore, the hermaphrodite is placed in a birch forest (this is one of the few species of tree with which the fly agaric can enter into a symbiotic relationship). According to interpretation s of alchemical symbolism, certain correspondences seem to emerge surprising clearly: the relationship between the sun and moon represented by the two heads and the two different coloured wings (red and white), which the mushroom precisely represents.

Figure 19 – Hildesheim Doors (Bernward)

Adam and Eve, Bernward’s Door of Salvation, St. Michael’s Church

Citation: Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3, 2; 10.1556/2054.2019.019

https://i2.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8459/8058928524_d813efa36e.jpg

they got pic from flickr

The next item we shall consider was located by the German chemist JOCHEN GARTZ (1996). It is a bas-relief from the bronze doors of the cathedra.l in Hildesheim close to Hannover (northern Germany) by an artist named Bernward, dating back to circa 1020 (fig. 19).

The scene following the Temptation, fairly realistically rendered, shows Adam and Eve who have already eaten the forbidden fruit.

They discover their nudity, and, covering their sex with an object, perhaps leaves, they speak with God.

[nakedness; lack of clothing; exposed; revealed; not covered; an un-covered state -mh]

God is asking Adam who ate the fruit, and appears to be pointing at him with His right hand. Adam covers his sex with his right hand and with the left points to Eve.

She covers her sex with her right hand and with the left points at the horrendous creature writhing on the ground at her feet, the incarnation of the Tempter.

There is a mushroom-tree between Adam and Eve upon which we may note two mushrooms with pointed striated caps.

This is the “Saint-Savin” type of mushroom (three striated mushrooms).

Here, the third mushroom has been consumed by Adam and Eve, as revealed by the broken branch springing from tbe lower part of the tree trunk.

The esoteric meaning would appear to be quite clear.

[“the esoteric meaning — never mind the broken branch, ITS A MUSHROOM! ACTUALLY EATEN; OMG MIND BLOWING! SO ESOTERIC!” -MH]

The mushroom-tree is realistically rendered with a precision not far short of anatomic accuracy and can be identified as one of the most common Germanic and European psilocybian mushroom, P semilanceata (Fr.) Quél.

This mushroom is endowed with a characteristic “papilla” [“a small projecting body part similar to a nipple in form” -mh] or “papillate umbon” surmounting the cap; this seems to indicate quite clearly that the artist intended to represent precisely this species of mushroom in his bas relief.

[not a mushroom, a parasol of victory -mh]

Heading

By way of summary, we may note that with the alchemical illustration (fig. 17) we have at least one example of the “Plaincourault” type mushroom tree with its four characteristics as defined and, here, we are justified in our strong suspicion that the artist wished to represent a psychoactive mushroom, the mushroom in question being A. muscaria (or the mushroom of the same genus, A. pantherina).

_____

With the German bas-relief of Fig. 19 we have al so found at least one “Saint-Savin” type mushroom, with its three typically striated caps, and here too we are justified in strongly suspecting that the artist intended to represent a psychoactive mushroom (the mushroom in question is a psilocybian).

Figure 20 – Table: Column 1: Amanita Mushroom Trees, Column 2: Psilocybin Mushroom Trees

Thus, we have discovered a precise typological differentiation among mushroom-trees in Christian art which corresponds with the variation in naturally occurring psychoactive mushrooms (cf. Fig. 20).

The only thing better, would be 3-column: Cubensis; Liberty Cap; Amanita.

We have to put AMANITA LAST, to correct the severe imbalance of coverage in the first phase of entheogen scholarship from say 1952-2009 (from Panofsky’s letter against the mycologists in 1952; to Irvin’s 3 books in 2009).

Look how the 3rd on left (Salamander) fits shape of Liberty Cap lower right — b/c hybrid; other ppl don’t get it, FANTASTICAL combination of Amanita/ Cubensis/ Liberty Cap.

2009-1952= 57 years of Amanita Madness imbalance among entheogen scholars.

— Michael Hoffman

Figure 21 – Basilica of Vezelay, France

Figure 22 – David & Goliath, Capital No. 50, Basilica of Vezelay, angle 1

Figure 23 – David & Goliath, Capital No. 50, Basilica of Vezelay, angle 2

I have recently identified another mushroom-tree on a capital in the famous Romanesque basilica at Vézélay (Fig. 21), this too in central France. This basilica’s hundred capitals dating back to circa 1135 are well-known and are probably the work of one sculptor. In Fig. 22 and 23, we see capital no. 50 with scenes from the biblical account of the struggle between David and Goliath (l Samuel, (7).

The anterior face shows David decapitating the Philistine giant with his sword; on the right side, instead, we have the next scene in which David carries the head of the giant on his shoulders as a trophy he will display to King Saul in Jerusalem.

The artist sculpted a mushroom-tree by David’s side in this scene and, il’ we look carefully, we may note that David, carrying Goliath’s head, is walking on some leaves, one of which belongs to the mushroom-tree.

This mushroom-tree might be considered of the “Saint-Savin” type, given the evident striations on the caps of the mushrooms, but here we have only two.

If we go back to the Hildesheim mushroom-tree (Fig. 19), we will remember that, although there were two mushrooms there too, we have an explanation for the absence of a third one (which in any case existed).

Here too, we are tempted to search for the third mushroom. Consider Goliath ‘s helmet in the preceding scene.

The shape and striations (grooves, or fluting) of the helmet are quite similar to those of the two mushroom caps of the mushroom-trees.

_____

If we examine one side of the capital (fig. 23) and bear in mind that it is located well above the viewer, the “illusion” created – if we may call it that – is of a mushroom tree with three caps.

For reasons of space, artists often had to eliminate details from scenes and would not hesitate to superimpose motifs and sequences otherwise represented in chronological order and therefore separately.

In the Tunisian mosaic at Béja (fig. 7), far example, we have Achilles and the centaur, Chiron. Here, three of the four mushroom-trees are without the third mushroom, probably due to lack of space.

_____

Considering this Vézélay capital, one might also be tempted to interpret the object which can only just be seen under David’s foot on the anterior face as the “third mushroom”. THOUNIEU (1997:149) comments:

“David is so small compared to the giant that he has to climb up a sort of plant in to decapitate him”.

This plant might taken for one of the many decorative leaf motifs which are a feature of the Vézélay stonework.

But it has a stalk and can hardly be thought of as a branch or petiole, and therefore might be a mushroom.

If this is the case, the esoteric message is unfolded before our eyes: to gain enough strength to decapitate Goliath (allegory of the struggle between good and evil), David must “ascend” by means of something which will “imbue” him with courage and strength.

Mushrooms, the form of which is the same as that of the mushroom-tree in other capitals in the same basilica.

Figure 24 – Bishop of Tours, Capital No. 26, Basilica of Vezelay

See, for example, the anterior face of capital 26 (fig. 24) representing the 4th century Bishop of Tours, St. Martin, as he preaches (he is known for his incessant efforts to convert pagans).

In the middle of this scene, we find a palm tree, which VrvlANE HUYS-CLAVEL (1996: 123) interprets as the “tree of the pagans” which St. Martin hurls insults at, the veneration of which St: Martin openly condemns.

On the top of the palm tree we see a mushroom. Is it mere chance that a tree believed to be “pagan” should also feature a mushroom?

There is something odd about this tree.

_____

Stylistically speaking, the mushroom poking out of the palm frond makes little sense; indeed, quite the opposite: it is an anomaly which seems to have been included to set this tree apart from the others and provide it with a separate meaning, as though the mushroom itself was an indication of the tree’s “pagan” nature.

The Vézélay master was meticulous at his job and the impression is that nothing was left to chance in these capitals. The wealth of allegorical and esoteric material in each scene is evident and, indeed, has been fully acknowledged by all scholars active in this field.

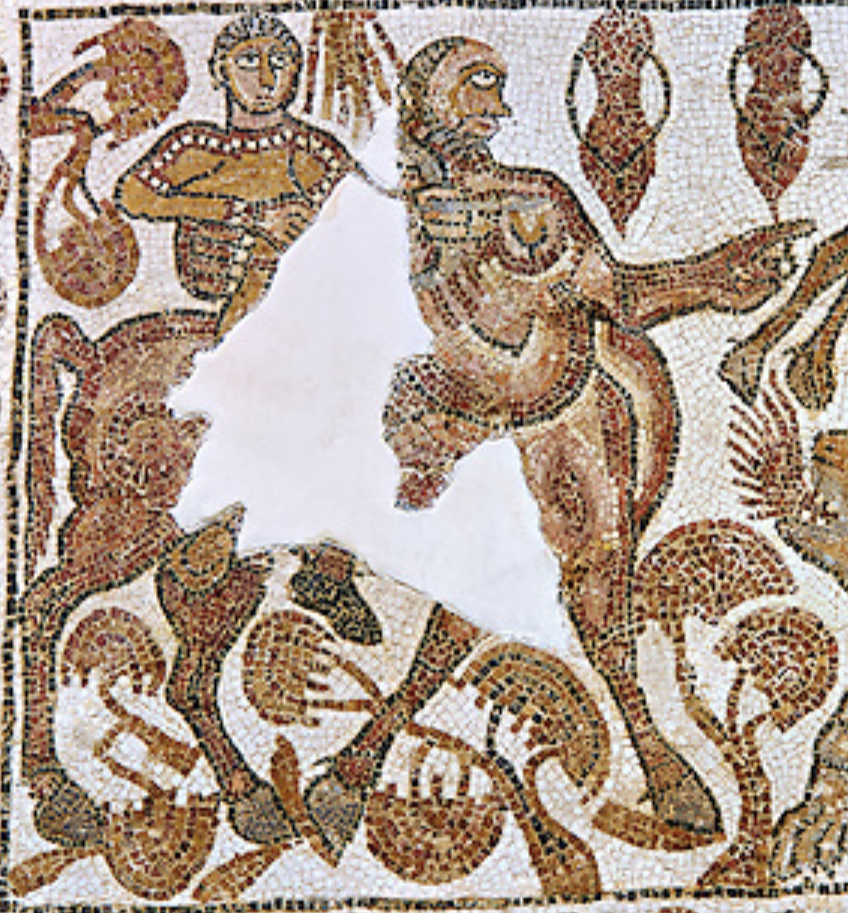

Figure 25 – Basilica di Aquileia

Lastly, I wish to refer to the observations made by da FRANCO FABBRO (1996), FRANCO FABBRO (1996) on one of the mosaics of the Christian basilica of Aquileia (Fig. 25) in northern Italy (the Friuli-Venezia Guilia region).

The mosaic forms part of the oldest paleo-Christian part of the basilica, known as the “Cripta degli Scavi”, dated 314 A.D. (cf. MARINI 1994).

Among the various subjects – animals, crosses, geometric symbols – we may note a basket containing mushrooms (Fig. 26).

Here, we have no mushroom-tree but mushrooms themselves, represented as such by the artist.

Perhaps this is the only existing example known to us to date of the evident representation of mushrooms in an early Christian church.

_____

Fabbro appears to have no doubts as to the species of mushroom presented: fly agaric.

Indeed, he is perhaps too self-assured and hasty in his conclusion that this Aquileia “find” provides corroborative evidence that the early Christians used fly-agaric.

As Francesco Festi of the Museo Civico in Rovereto and I concluded (FESTI & SAMORINI 1997), the mushrooms represented in the Aquileia mosaic were probably Amanita caesarea , also known as “ovulo buono ” (royal-agaric), an edible mushroom considered a delicacy by the ancient Romans and often included in the figurative works of the Roman imperial period.

We based our view on the fact that the mushroom stalks are yellow and not white, this being one of the distinguishing marks between these two species.

However, after paying a visit to the basilica I did note that the part of the mosaic corresponding to the inside of the caps, the gills, is white, as are the gills of the fly-agaric, and not yellow (as in the royal-agaric).

Furthermore, while the gills of the royal-agaric are always yellow, in some cases the gills and stalk of fly-agaric present gradations of yellow (ARIETII & TOMASI 1975: 1 06).

It was also noted that the artist had circumscribed the various areas of the mosaic to be filled in with different colours with dark-coloured fragments, which means that the wrong colour of fragment would not be able to make its way into another circumscribed zone of another colour.

Therefore we may conclude that the artist wished to portray these mushrooms specifically with white gills, and that there is good reason to doubt that these mushrooms are in fact A. caesarea. Another feature of this mosaic is that two of the eight mushrooms have stalks which are not entirely yellow but also white.

_____

The Aquileia mushrooms would therefore appear not to be explicitly represented as belonging either to the fly or the royal agaric species. Representation of the royal agaric would not call for subterfuge, but fly agaric would. However, this may be yet another species of mushroom or quite simply a generic “mushroom”. It has been hypothesized that the mosaic represents the food (including mushrooms) the faithful consumed during agapes (mysterious ritual feasts held by early Christians) (Brusin & Zovatto 1957, cito in FABBRO 1996).

_____

I fully appreciate just how complex an investigation of this kind is, how many pitfalls await the researcher, and how easily he may be “led up the garden path”. I therefore prefer not to offer my own interpretations of the various works of art presented here. [already done -mh]

_____

In any case, we may confidently conclude from what has emerged that justifications do exist for serious and unprejudiced ethnomycological study of early Christian culture, and it is our hope that such studies will take place.

Acknowledgments

l wish to thank the following for the aid and suggestions regarding the material presented in this article:

- prof. Elemire Zolla (Montepulciano, SI, Italy);

- Francesco Festi (Museo Civico di Rovereto, TN, Italy);

- Dona & Manuel Torres (Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA);

- Dr. Guido Baldelli (Monzuno, BO, Italy);

- Jonathan Ott (Natural Products, Xalapa, Vér., Mexico);

- Josep M. Fericgla (Institut de Prospectiva Antropologica, Barcelona, Spain);

- Tjakko Stijve (Nestlé Research Centre, Lausanne, Switzerland);

- lochen Gartz (University of Leipzig, Germany).

Bibliography

ARIETTI NINO & RENATO TOMASI, 1975, l funghi velenosi, Edagricole, Bologna. BECKER G., 1989, Setas, Susaeta, Madrid.

BENNETT CHRIS, LYNN OSBURN & JUDY OSBURN, 1995, Green Gold the Tree ofLife. Marijuana in Magic and Religion, Access Unlimited, Frazier Park, CA.

CALVETTI ANSELMO, 1986, Fungo Agarico muscario e cappuccio rosso, Lares, 52:555-565.

CANESTRINI DUCCIO, 1985, La salamandra, Rizzoli, Milano.

CHARBONNEAU-LASSAY LOUIS, 1994 (19.), Il Bestiario del Cristo, 2 volI., Arkeios. Roma.

CHARBONNEAU-LASSAY LOUIS, 1997, Le Pietre Misteriose del Cristo, Arkeios, Roma.

COOK ROGER , 1987, L’Albero della Vita, RED, Como.

FABBRO FRANCO, 1996, Did Early Christian used Hallucinogenic Mushrooms? Archaeological evidence, on web: http://www.etnoteam.itlmaiocchi.

FANTAR H. M’HAMED (Ed.), 1995, l mosaici romanici di Tunisia, Jaca Book, Milano.

FERICGLA M. JOSEP, 1993, Las supervivencias culturales y el consumo actual de Amanita muscaria en Catalufia, Ann.Mus. Civ.Rovereto, Suppl. voI. 8:245-256.

FERICGLA M. JOSEP, 1994, El Hongo y la génesis de Las culturas, Los Libros de la Liebre de Marzo, Barcelona (originally [text missing]

FESTI FRANCESCO, 1985, Funghi allucinogeni. Aspetti psico fisiologici e storici, LXXXVI Pubblicazione dei Musei Civici di Rovereto, Rovereto (TN).

FESTI FRANCESCO & ANTONIO BIANCHI, 1991, Amanita muscaria: mychophannacological outline and personal experiences, Psyched.Monogr.& Essays, 5:209-250.

FESTI FRANCESCO & GIORGIO SAMORINI, 1997, Pers.comm.

GARI LACRUZ ÀNGEL, 1996, La brujerfa y los estados alterados de consciencia, in: J.M. FericgIa (Ed.), Actas del Il Congreso Internacional para el Estudio de los Estados Modificados de la Consciencia, Lèrida, Octubre 1994, Institut de Prospectiva Antropologica, Barcelona, : I 4-21.

GARTZ JOCHEN, 1996, Magie Mushroom Around the World, LIS, Los Angeles, CA.

GRABAR A. & C. NORDENFALK, 1958, Romanesque Painting. XI-XIII Centuries, Skira, Lausanne, Switzer1and.

GRASSI BATISTA, 1880, Il nostro Agarico Muscario sperimentato come alimento nervoso, Gazz.Ospit.Milano, 1:961-972.

GRAVES ROBERT, 1984, Las dos nacimientos de Dionisio, Seix Barea1, Barcelona.

GRAVES ROBERT, 1992, La Dea Bianca, Adelphi, Milano.

GRAVES ROBERT, 1994, La comida de los centauros y otros ensayos, Madrid, Alianza.

GUZMÀN GAST6N, 1983, The genus Psilocybe, Nova Edwigia voI. 74, Cramer, Vaduz.

GUZMÀN GAST6N, 1997, Pers.comm.

HEINRICH CLARK, 1994, Strange Fruit: Alchemy, Religion and Magical Foods: A Speculative History. “January 1, 1995” per Amazon. [This citation is missing from the Bibliography of Samorini’s article. -Cybermonk]

HUYS-CLAVEL VIVIANE, 1996, La Madeleine de Vézélay. Cohérence du décor sculpté de la nej, Comp’ Act, Chambéry.

KURT R., 1987, Gnosis: the Nature and History oj Gnosticism, Harper San Francisco, New York, N. Y.

LABANDE-MAILFERT YVONNE, 1974, Le cycle de l’Ancient Testament à Saint-Savin, Rev.Hist.Spir. , 50:369-396.

LAZZARI GIACOMO, 1973, Storia della micologia italiana, Saturnia, Trento.

MARINI GRAZIANO (cur.), 1994, La basilica patriarcale di Aquileia, SO.Co.B .A., Aquileia.

MORGAN ADRIAN, 1995, Toads and Toadstools , Celestial Arts, Berkeley, CA.

OTT JONATHAN, 1997, Pharmacophilia or The Natural Paradises, Kennewick, WA, natural Products.

OURSEL RAYMOND, 1984, Haut-Poitou Roman, Zodiaque, Ab. St. Marie de la PielTe-qui-Vire.

PIOMELLI DANIELE, 1991, One route to religious ecstasy, Nature, 349:362.

PUECH HENRI-CHARLES, 1949, Le cerf et le serpent, Cah.Archéol., 4: 17-60.

RIOU YVES-JEAN, 1992, L’abbaye de Saint-Savin-surGartempe, L’ Inventaire, Ministère de l’Education et Culture.

SAMORINI GIORGIO, 1996, Un singolare documento storico inerente l’agarico muscario / A peculiar historical document about Fly Agaric, Eleusis, 4:3-16.

SAMORINI GIORGIO, 1997, L’albero-fungo di Plaincourault/ The mushroom-tree of Plaincourault, Eleusis, 8:29-37.

STAMETS PAUL, 1996, Psilocybin Mushrooms of the World, Ten Speed, Berkeley, CA.

STIJVE TJAKKO, 1994, Pers.comm.

THOUMIEU MARc, 1997, Dizionario d’iconografia romanica, Jaca Book, Milano.

WASSON G. ROBERT, 1968, Soma. Divine Mushroom oj Immortality, HBJ, New York.

WASSON P. VALENTINA & ROBERT G. WASSON, 1957, Mushrooms, Russia and History, Pantheon, New York.

ZOLLA ELEMIRE, 1979, I funghi-bambini di Maria Sabina, Giornale di Brescia, Venerdì 7 Settembre.

Notes by Cybermonk

Citation & Link for “Mushroom-Trees” in Christian Art (Samorini 1998)

Article by Giorgio Samorini

Journal issue: Eleusis, n.s., 1:87-108, 1998

The source file, original article:

https://www.samorini.it/doc1/sam/sam-alberifungo-1998.pdf

Extracted images, added to the most major collection on the Web, of images of mushrooms in Christian art:

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2020/12/13/images-of-mushrooms-in-christian-art/#Samorini-Mushroom-Trees-in-Christian-Art

“The mushrooom-tree of Plaincourault” (Samorini 1997)

Samorini’s earlier article:

The Mushroom-Tree of Plaincourault (Samorini 1997)

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2022/04/16/samorini-plaincourault-mushroom-trees-article/

Direct link to Samorini’s .PDF of 1997 article:

https://www.samorini.it/doc1/sam/sam%20plaincourault.pdf

Samorini’s ~2002 Book Including a Version of the Articles: FUNGHI ALLUCINOGENI: STUDI ETNOMICOLOGICI

Italian. https://www.samorini.it/doc1/sam/samorini-funghi-allucinogeni-studi-etnomicologici.pdf

FUNGHI ALLUCINOGENI: STUDI ETNOMICOLOGICI

About this Page (mh)

I made the present page because I read by highlighting, reformatting, & commenting. The present page links to Samorini’s PDF URL.

I started this page December 20, 2020. Update April 17 (Easter) 2022: Need to add real heading text and link the TOC entries.

Added Clark Heinrich citation (Strange Fruit, 1994/”January 1, 1995″) which is missing from the Bibliography of Samorini’s article.

— Michael Hoffman/Cybermonk

Enhancements and Additions I Made

- English Text Only

- I copied the English (not Italian) text from the PDF to this WordPress page.

- Text Recognition Errors

- There are many text-recognition errors, though the PDF is legible; check the PDF. The PDF is legible, and has images inline.

- I’m adding the Headings

- Paragraphing — Samorini lacks section headings, but has 25 figure numbers that can drive adding sectioning/ headings.

- I Added My Commentary, with: -mh

- I consistently indicate my notes with “-mh”; you can Find: -mh

- I Added Highlighting

- I add bold emphasis; Samorini’s article in Eleusis journal doesn’t use bolding.

- Added color versions of his images.

- Added color of Brown’s photo of parasols zoom

- Added research links.

- Added a Table of Contents

- Broke up his long, dense paragraphs.

- Between each of Samorini’s paragraphs, I insert an underscore line:

_____ - Broke sentence into its own paragraph, surrounded by space vs. Samorini’s packed.

- Added heading for each of 25 Figures. Linked toc.

- Between each of Samorini’s paragraphs, I insert an underscore line:

— Michael Hoffman

The Role of Mushrooms in Christian Art (mh)

commentary section by Michael Hoffman

Against Samorini’s moderate position, my position in the subfield of mushrooms in Christian history is the maximal mushroom theory of Christian art.

Mushroom shapes in Christian art represent psychoactive mushrooms (especially Psilocybe), ingested to produce religious experiencing.

Mushrooms cause religious experiencing.

Species of mushrooms that contain psilocybin are the main, authoritative, paradigmatic, reference entheogen for Hellenistic religion and for religion in Christendom.

Psilocybin mushrooms are the primary, standard way of producing religious experiencing throughout Christian history.

Christian art depicts otherworldly, fantastical, stylized, non-realistic, religious mythology.

Religious mythology describes by analogy, entheogens producing the intense mystic altered state, eventually causing transformation of the mental worldmodel from possibilism to eternalism.

{king steering in tree} -> {wine} -> {snake frozen in rock}

How the “Evolutionary Anthropology” Approach Is Utilized to Suppress Mushrooms in Christian Art by 50-100% (mh)

Against the “Evolutionary Anthropology Commentary/ Analysis” Style

commentary section by Michael Hoffman

I’m strongly picking up a smell of a certain presupposition-set driving Samorini’s commentary.

Avoiding the maximal mushroom theory of Christian history, and assuming Whiggish Darwinist evolutionary psychology (from dumb primitives, to Wonderful Us), go hand-in-hand.

If you are a mental slave to the “evolutionary psychology” assumption-framework, you will corrupt and twist your thinking when trying to say “this earlier painter did/didn’t recognize that their mushroom is a mushroom, but this later painter didn’t/did.”

You introduce arbitrary assumptions that half mushrooms in Christian art don’t mean mushrooms.

Letting “evolutionary psychology” drive and dominate your thinking, forces you to assume a priori, based on presuppositions, that HALF the mushrooms in Christian art weren’t recognized by the stupid primitive confused artist.

It’s not just Samorini’s analysis-effort-style; it’s a mindset that ruins topics, it’s heavy-handed and obvious, even showy — making a show of talking in this certain affected way, with tell-tale or a set of deliberate signalling, where you stand in judgement over the field and declare how it evolved from “primitive yet wise”, to “evolved yet lost something”.

The result is Samorini’s arbitrary, waffling, self-contradictory random sprinkling of phrases like “peasants still had some fading recollection, now forgotten, that the imagery meant mushrooms, which they still recalled, as evidenced by the folk-names they use….”

Where he writes “probably” or “most likely“, Samorini (or anyone employing this academic stance) is engaging in that mode, to covertly remove 90% of mushrooms, with no specific justification — acting as if to “understand” a field is to strike a pose of plotting the trajectory of its “evolutionary anthropology/ evolutionary consciousness”.

The goal of this game is to declare and pronounce, as often as you can get away with, that “the painter was ignorant of psychoactive mushrooms”, while having no basis whatsoever to make such a pronouncement.

Per the maximal mushroom theory of Christianity, I simply, always, consistently assume that if a painter painted mushrooms, the painter meant ingesting psychoactive mushrooms (such as Cubensis and Liberty Caps) to deliberately induce religious experiencing; the intense mystic altered state.

I challenge anyone to justify assuming that painters created mushroom shapes without intending deliberate use of mushrooms for religious experiencing, given that:

- Mushrooms induce religious experiencing.

- People before us were not idiots.

- Religious art is otherworldly and mythological, not literalist.

I also assume – consistently, not on an arbitrary per-case basis – that whenever an artist depicts unnatural branching, the artist is asserting eternalism rather than possibilism.

There’s no “evolution of consciousness” to be speculated upon like Samorini & everyone does, in “19th C anthropologist Affectation” style.

Don’t distort and complicate it by dragging in sketchy, lost-up-your-own theory, over-intellectualized Whig theories of trajectories of cultural-consciousness evolution.

There are rules of this stupid game.

Assume painters are stupid, assume you are smart, and you get to sit in judgment over painters who you think are too stupid to know they are painting a mushroom, or that mushrooms make you trip.

Who’s the stupid, dense, primitive & confused thinker here? The pompous, as-stupid-as-proud, late-modern Anthropologist.

It’s actually the academics who are embarassingly stupid. When you write in this mode, you are supposed to play a certain game, of speculating about the trajectory of incomprehension of the primitive mind.

Never consider that the painter is smart and astute enough that maybe he’s an expert on mushroom effects and is painting a hybrid of Liberty Caps, Cubensis, and Amanita, along with themes of branching and non-branching.

These assumed-primitives you stand in judgment over, inventing all your pseudo-sophisticated cargo-cult Darwinesque categorization schemes, pompous scientistic posturing, —

The allegedly primitive clueless painters you stand in judgment over, are probably wise experts and would be so insulted at some clueless whig scholar yapping about “unknown to the painter, this stylization derives from psychoactive mushrooms.”

Get rid of 90% of mushrooms, on the basis of 19th C evolutionary anthropology theory that enables to you simply assume most people are too dumb to know they’re painting mushrooms.

Assumption:

Artists are too stupid & ignorant to know that they are painting a mushroom.

Conclusion:

90% of mushroom shapes in art aren’t mushrooms, according to the artist.

-mh

Weblog Notes by Cybermonk

https://egodeaththeory.wordpress.com/2022/04/16/samorini-plaincourault-mushroom-trees-article/